Hey, Big Brother? It’s me. Can we talk about facial recognition please?

The Download Festival

See, the police used facial recognition technology to scan the faces of thousands of attendees at the Download music festival in the UK without their knowledge.

The excuse the Leicestershire Police used was that they were trying to catch “organized criminals” who specifically target music festivals to “steal mobile phones,” according to a report in Police Oracle. The collected footage is compared against a database of custody images to identify the criminals, in this case, an alleged music festival phone-robbing crime ring that nobody seemed to have heard about prior to it becoming the justification for searching an entire crowd who did nothing but show up to hear some tunes.

The festival saw 91 arrests out of 100,000 people. Most were for alcohol-related mishaps, none for phone theft.

Facial Recognition Technology

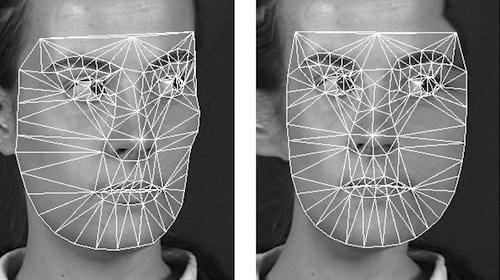

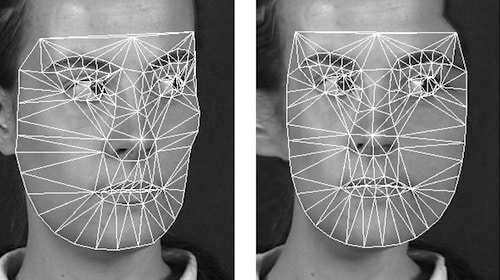

Facial recognition technology is big business. The tech is evolving rapidly. Basically a computer digitizes an image of someone’s face in a way that makes fooling the system difficult, stuff like measuring the distance between eyes, the angle of one’s nose, ear lobe shape, the sort of stuff that can’t be thrown off by face paint, a hat, sunglasses or the like. And the software can be configured to zero in on someone who is wearing face paint, a hat and sunglasses, so nice try, you in the back row. You’re now a person of interest.

Facial recognition is increasingly being used by law enforcement. In the US, it’s used by the FBI and local police departments. The largest scale use of the tech in America is at major sporting events like the Super Bowl, supposedly because terrorists are flocking there, even though they never have.

Reports suggest airports scan passengers, hotels scan lobbies, stores scan aisles, casinos scan their gambling floors and many police street cameras are tied into the systems. Another publicly-known example occurred after the Boston Marathon bombing of April 2013. The subsequent Boston Calling music fest was subject to heavy use facial recognition surveillance, one guesses in case there were more Tsarnaev brothers out there.

Nobody wants the World Series blown up by terrorists. And guess what — neither before nor after 9/11 has any terror group carried out a mass casualty attack (if you want to count the goofball Tsarnaev brothers in Boston as a terror group, and the [unfortunate] deaths of the three spectators there was “mass,” be my guest.) And of course neither facial recognition tech nor anything else seems to deter our regularly-scheduled mass shootings (been to the movies lately?)

Why It Matters

The concern over widespread and indiscriminate use of mass surveillance technology, such as facial recognition, is that it is widespread and indiscriminate, a form of search (your location) and seizure (your image and location data) that, in the US at least, thumbs its nose at the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment protections against unwarranted actions. So it is simply wrong on its, well, face.

Someone inevitably will respond to all this with a hearty “Well, I’ve got nothing to hide.”

Good for you. You are quite a person if you indeed have nothing at all to hide. And maybe you really don’t, at least under today’s laws.

But information collected never goes away. Your “nothing to hide” argument has built into it your full and true faith that every government, every company, every hacker that can, will or might gain access to that data will never do anything with it against your self-interest. You are asserting that no new technologies will emerge to manipulate that data in a way you blearily can’t conceive of now.

That, my friend, is a lot of faith in Big Brother.

Reprinted with permission from We Meant Well.