Inevitably the debate over issues that relate to both national security and domestic law enforcement often become mired down in wrangling over legal or constitutional niceties, which the public has difficulty in following as it fixates instead on the latest twist in the Bruce Jenner saga. That means that the punditry and media concentrate on easily digestible issues like potential bureaucratic fixes, budgeting, equipment and training, which presumably are both simpler to understand and also more susceptible to possible remedies. But they ignore some basic questions regarding the nature and viability of the actual threat and the actual effectiveness of the response even as the dividing line between military and law enforcement functions becomes less and less evident.

There has been a fundamental transformation of the roles of both police and the armed services in the United States, a redirection that has become increasingly evident since the 1990s when the conjoined issues of national security and crime rates became political footballs. Response to terrorism and “tough on crime” attitudes frequently employ the same rhetoric, incorporating both political and social elements that place police forces and the military on the same side in what might plausibly be described as a version of the often cited clash of civilizations.

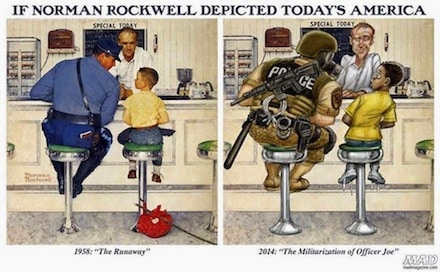

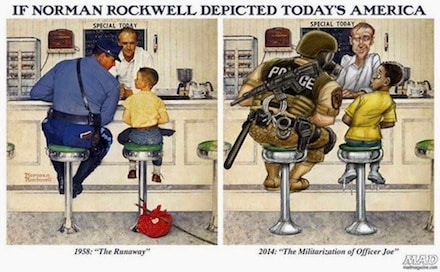

A nation’s army traditionally exists to use maximum force to find and destroy enemies that threaten the homeland. A police force instead serves to protect the community against criminal elements using the minimum force necessary to do the job. Those roles would appear to be distinct but one might reasonably argue that the armed forces and the police in today’s America have become the two major constituents of the same organism more-or-less connected by a revolving door, dedicated to combating a new type of insurgency that comprises both global and domestic battlefields and is no respecter of borders. This has meant at its most basic that there has been a major shift in perception on the part of the security community. Community policing and national defense have abandoned relatively reactive interactions with the community and world for more assertive preemptive roles that see their areas of operation as theaters of conflict analogous to war zones, suggesting to some law enforcement officers that Baltimore is at least occasionally somewhat like Fallujah.

That means that some police forces have allowed considerable space to develop between themselves and the communities they are supposed to guard. Many now see themselves less as crime solvers and protectors of the public, instead increasingly embracing their role as a first line of defense against terror and social unrest. As a consequence, police in today’s America are inevitably tasked with maintaining public order in a fashion that once upon a time would have likely been the responsibility of the military equipped and trained as well as far more numerous National Guard.

This tendency to expand and redirect the police role gained momentum in the early 1990s, when law enforcement began to focus on terrorism in the wake of Oklahoma City and the first World Trade Center bombing. After 9/11 it picked up speed when the Bush Administration rushed to adopt a preemptive foreign policy that fit in nicely with a more assertive role by police. Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) teams were symptomatic of the change. Originating in Los Angeles in the 1960s, SWAT units spread to nearly every major and many minor police departments whether there was or is any need for them or not. Police departments, embracing having a exciting new weapon and looking for excuses to use it, began to allocate tasks that normally had been the responsibility of beat or patrol officers, including serving warrants. SWAT delivery of what are described as “no-knock” warrants that are frequently issued without any real justification and sometimes based on faulty intelligence has consequently become a bete noire for critics of police overreach. The warrants are sometimes served in the middle of the night by heavily armed officers and might well be preceded by the use of battering rams and “flashbang” grenades, resulting in numerous tragedies for those on the receiving end. With SWAT teams attracting the elite police officers, community policing inevitably has suffered, frequently being assigned to new and less experienced officers.

Police and the military now share equipment, training and doctrine. The equipment, most of which is useful for fighting a war but of marginal utility for police work, is frequently highly visible and changes both how local law enforcement is perceived and how it operates. Arizona alone has received 29 armored personnel carriers, 9 military helicopters, 800 M-16 automatic rifles, 400 bayonets, and 700 pairs of night-vision goggles.

Morven, Georgia, population 600 and blessed by a low crime rate, has received over $4 million worth of military equipment. This led to the formation of a SWAT team supported by a Humvee and an armored personnel carrier. Boats and scuba gear came together to form a dive team, even though Morven city limits incorporate no body of water deep enough to exploit that capability. The Morven police chief boasts that the equipment would enable him to “shut this town down” and “completely control everything.”

The direct transfers of $5.4 billion worth of surplus equipment from the Pentagon through program 1033 and the purchase of additional hardware by way of grants from the Department of Homeland Security operate with almost no oversight over the actual need for the equipment and little accountability afterwards regarding where it winds up. It has spawned what some have described as a police-industrial complex, which is frequently justified by the alleged terrorist threat even though the equipment is in fact almost never used in response to terrorism related situations.

Today’s police approach every potential conflict situation with overwhelming force because that is what the military does, considering “force protection” as its number one priority. The army and law enforcement also share employees, guaranteeing that the mindsets within the two organization will be highly compatible. There are no national figures compiled on how many policeman have been in the military, but anecdotal evidence from various departments suggest that the percentage is somewhere between 20 and 60 per cent, many of whom also continue to serve in the Reserves or National Guard. A veterans’ placement service called Hire Heroes estimates that fully twenty per cent of all ex-soldiers seeking civilian employment look for work in law enforcement as a first choice.

The Federal government also encourages police departments to hire veterans through its Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS), which has provided $114.6 million in incentive grants to 220 cities nationwide. There is frequently a comfortable fit psychologically. The transition from military to police is particularly smooth currently because their self-perceptions as “forces for peace and security” working in environments where they are not appreciated or even welcomed is nearly identical.

On the plus side when turning soldiers into cops, former military are accustomed to operating in a highly disciplined and rule-driven top-down organization, but on the negative side veterans who actually experienced significant combat are much more accustomed to rely on their weapons than are policemen in most working environments, a predilection that sometimes produces avoidable fatal consequences. The window of aggression acceptable to a soldier on a combat patrol is and should be radically different than that of a policeman in an American city.

Returning soldiers who experienced significant combat sometimes come home with mental health issues to include Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), with many veterans conceding that after discharge from the service there are sometimes numerous psychological issues that have to be worked through. Police departments do their best to manage that issue through psychiatric screening, but detection of problems is not always that easy, particularly if the job applicant wants the job and is not being particularly forthcoming. Many concede that for ex-soldiers thus afflicted leaving one environment full of “violence, tension, stress [and] anxiety” and landing into something similar would not exactly be therapeutic.

Law enforcement in the United States has also benefitted not only from the surplus weapons it receives from the Pentagon but also from training grants and logistical support from the Department of Homeland Security. Many SWAT teams are trained by and often include former or current Special Forces soldiers. Some departments even use both public and private grant money to send officers to Israel to train with the Israeli National Police and that country’s Defense Force. The training inevitably focuses on counter-terrorism, anti-riot procedures, intelligence gathering and crowd control, reinforcing the impression that such activities that once upon a time might have regarded as peripheral to police work are now the first priority. There are also reports that some American police forces are interested in buying an Israeli high tech export called “Skunk,” which is a liquid that can be sprayed from water cannons that allegedly smells like raw sewage and putrefying flesh. It has been used on Palestinian protesters.

But perhaps the biggest unanswered question is “Does terrorism in its many guises actually threaten the United States and will that threat be diminished by more equipment and training as well as a more militarized police force here at home?” Addressing the threat issue is critical as it presents a steady drumbeat for action “to defend the nation” and actually provides much of the popular support for an increasingly robust police response. To be sure, there undoubtedly exists a growing critical consensus that the terrorist threat is largely phony, having been inflated by both political parties for political reasons. Certainly the record of terrorism related arrests suggests that the danger is minimal and those detained in the process are often the product of what many would call law enforcement entrapment. There is actually no evidence that a more militarized police has thwarted terrorist attacks or led to any significant arrests, which rather suggests that the real motive for the increasingly assertive profile for law enforcement might just be to have the tools on hand to intimidate or even put down domestic dissent. If that is so, every American should be concerned about what might be coming down the road.

Reprinted with permission from Unz Review.