As an interdisciplinary researcher studying both epidemiology and economics, I worry that differences in evidentiary standards of these fields predispose us to harming people indirectly through the economy in the service of preventing harm in a pandemic.

When SARS-CoV-2 infects a patient’s lungs and the patient tragically dies due to respiratory failure, it’s clear that the patient died because of SARS-CoV-2. If we follow the chain of causation backward before a patient’s death, there are additional causes we can identify – a chain of transmissions connecting one person to another all the way back to a bat.

Throughout the pandemic, we’ve relied on this very clear chain of causation in combination with the “precautionary principle” in the service of preventing people from dying from Covid. However, our application of the precautionary principle has combined with a causal myopia and this has served the precautionary principle to cause very real harm to very real people.

The precautionary principle is a way we justify action in the face of uncertainty and, crucially, inaction in the face of innovations that may cause harm. Before Covid, for example, the precautionary principle was applied to genetically modified crops, arguing that because we don’t know the potential ecological harms from this innovation, we should proceed forward with excessive caution.

A central idea in the precautionary principle is to anticipate harm before it happens. Anticipating harm, however, requires an understanding of the chain of causation leading to harm. If we introduce GMOs, we can anticipate ways they can impact pollinators, breed with non-GMO plants, and potentially destroy ecosystem services on which we rely. We can clearly see many links in the chain of causation when a patient dies with SARS-CoV-2, and throughout the pandemic we’ve justified public health interventions in anticipation of these epidemiological harms.

From the first reports of a “pneumonia of unknown etiology” in Wuhan to more recent news of Omicron discovered in South Africa, global policymakers have implemented a range of travel and trade restrictions to lockdowns mandating people shelter in place. These policy choices were believed to be urgent actions in service of excessive caution to prevent anticipated harms from a pandemic. Throughout the pandemic, we’ve combined our understandings of infectious disease causality with the precautionary principle to act. In anticipation of harm to diners, we closed restaurants. In anticipation of harm caused to teachers, we closed schools.

While these actions may have stopped transmission chains from causing deaths in some patients, they have caused harm to others. We react to the clear and now popularly understood causal chains of transmission, but our actions cause harm through more complex andless popularly understood causes, but the harm we cause is as real as the harm we prevented.

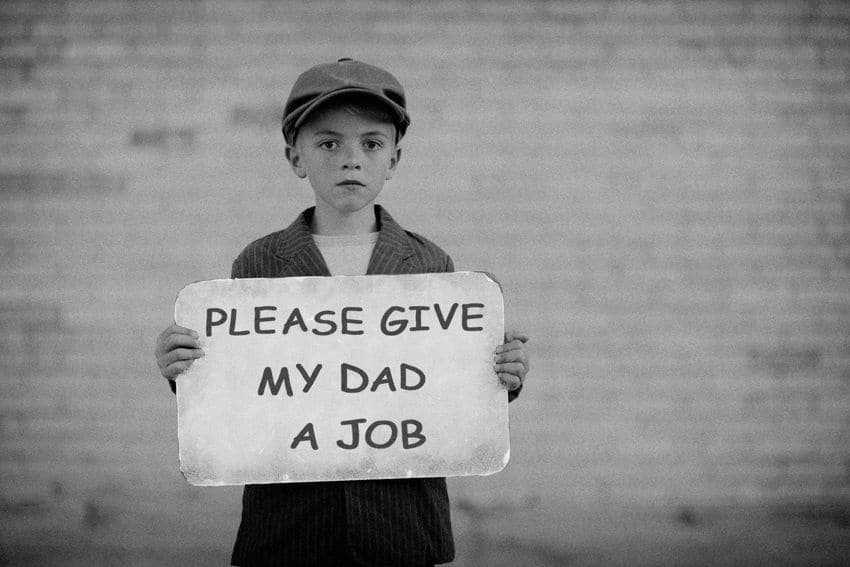

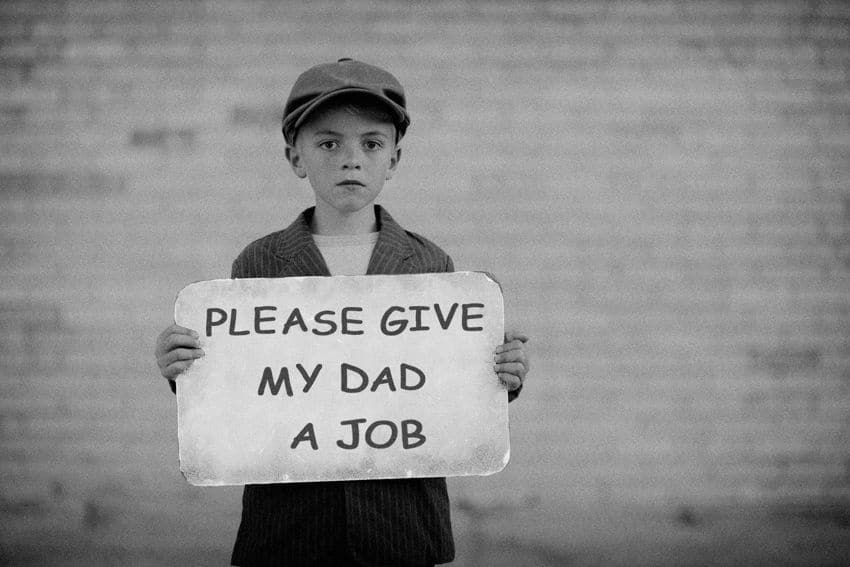

When a person in Africa making $1 a day no longer makes that $1 a day, can no longer afford food, goes hungry, and dies from hunger, the preceding chain of causation is far more complex. What caused the person to die of hunger? Was it the global inequities where some people live day to day on $1 while others sit on $1 billion? Was it geopolitical conflict, itself caused by forces tracing back to the origin of humanity itself? Or, did the person die because of our policy decisions to shut off travel andtrade, depriving them of the $1 lifeline they depended on?

They died because of all of these causes and more, but one crucial link in this causal chain was a decision that we made, an action we took. By failing to acknowledge the diffuse harms of pandemic policy, we’re undermining tomorrow’s scientists and public health officials who aim to apply the same precautionary principle for the next pandemic.

How we assign cause is evident in how we talk about the pandemic. It’s fashionable these days to write articles on how “The Pandemic” caused unemployment to spike, supply chains to be disrupted, inflation to rise, and 20 million extra people predominantly in Africa and Asia to suffer from acute hunger. It’s fashionable to write about how “The Pandemic” caused millions of kids in Latin America to drop out of school, and how “The Pandemic” caused a rise in deaths of despair.

By attributing these deaths to a nebulous and agentless causal source – “The Pandemic” – these articles bypass accountability for our actions, the actions of policymakers, and the actions of scientists consulting managers on the risks of Covid and competing risks of other causes of harm. Despite evidentiary differences in epidemiology and economics, there are clear causal chains connecting our actions preventing harm to elderly patients in America to impoverished young people dying of acute hunger outside our borders. “The Pandemic” did not cause most of this collateral damage – our actions did.

These negative consequences from our collective social reactions and policy choices in the pandemic are tough pills to swallow. The scientists, public health officials, and government officials at various stages of the pandemic were faced with extremely difficult choices. The complexity of the situation and lack of modern precedent requires empathy as we have these discussions; it’s crucial we distinguish between malice, of which there was little, from mismanagement, of which there was a lot.

It’s essential we debrief on the harm we caused – the epidemiological harm we simply displaced andconverted to economic harm that, at the end of the chain, has caused equally real people to suffer and die at higher rates than they would’ve had we acted differently.

It’s irresponsible and unscientific to suppress discussions on the inconvenient truth that our response to the pandemic likely indirectly killed people. If scientists are to maintain a moral high ground in their efforts to apply precautionary principles in climate change, antibiotic resistance, deforestation, mass extinctions, and other pivotal issues of our time, we have to demonstrate our ability to learn from our mistakes.

An unsettling yet familiar possibility is that we are probably bypassing accountability for our actions because they caused harm to people in lower socioeconomic circumstances. If our policy choices caused 20 million of the richest people in the world to face acute hunger, the connections between our policies and the harms they caused would be discussed every day.

At a time when many scientists were tweeting that Black Lives Matter following the death of George Floyd, they supported pandemic policies which worsened outcomes for BIPOC lives in America and caused millions of people in low-income countries to suffer from acute hunger. At a time when scientists claimed their policies were about equity and avoiding epidemiological harm, they failed to consider epidemiological and economic harm caused to disproportionately BIPOC essential workers, to disproportionately poor kids dropping out of schools, to young men at risk of deaths of despair when sheltering in place, to hard-of-hearing kids (like myself) who read lips but can’t read masks.

My point here is not that anyone is racist or had malicious intent. Far from it – I sincerely believe that 99% of the scientists and managers speaking up in the pandemic were trying to save lives and were constantly considering the morality of their actions. Rather, my point is that many people – from scientists to the managers they consulted – lacked positionality to understand how their choices affected people in different circumstances.

Additionally many infectious disease epidemiologists applying the precautionary principle to prevent viral harms were not sufficiently knowledgeable of economics and public health to assess the competing risks, the other inconvenient causes and harms that resulted from our actions.

The unfamiliarity of causal chains connecting travel restrictions from high income countries and economic disruptions to a death from hunger in Africa reveals a causal myopia, a neglect of other causes of harm to other people from different sectors of the economy, different socioeconomic backgrounds, different races, and different countries.

While the chain of causation connecting our social and policy reactions to the pandemic may be difficult for many to understand, the people harmed are just as real, and their lives, health and well-being matter. Applying the precautionary principle to justify policies that prevent harm evident to one field of study but cause harm evident to another field undermines the precautionary principle that we need to navigate major challenges human civilization faces in the decades ahead.

There are costs of caution when the precautionary principle considers one field’s causes of harm while ignoring another’s. We owe it to the victims of the pandemic to study and improve our understanding of epidemiological causes and improve our tools for managing pandemics.

Similarly, we have a responsibility to help kids who dropped out of schools, to young people who died deaths of despair, to essential workers who brought a virus into a multigenerational home, and to those outside our borders who suffered and died from acute hunger. We owe it to them to understand that the political and economic causes of their harm, though more complicated than a virus causing death, are just as real as the epidemiological harms we tried to prevent.

“The Pandemic” didn’t cause these harms. We did.

Reprinted with permission from Brownstone Institute.