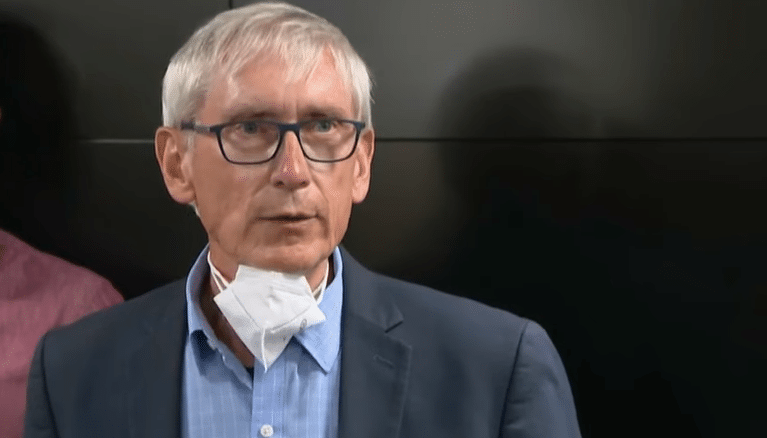

The Wisconsin Supreme Court blocked Democratic Gov. Tony Evers from issuing any new public health emergency orders to mandate face masks. In a 4-3 decision that broke along ideological lines, the conservative majority found that Evers lacked authority for his order. It is similar to a ruling rejecting orders by Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. What was most striking was the dissenting opinion from the three liberal justices. The dissenting justice adopted the most convoluted and artificial construct to ignore the plain meaning of the controlling state law.

Justice Brian Hagedorn wrote for the majority based on the express language of the state law that mandates that governors may issue health emergencies for 60 days but then the Legislature must approve any extension. Thus, Hagedorn wrote “The question in this case is not whether the Governor acted wisely; it is whether he acted lawfully. We conclude he did not.”

Look at the operative language and see if you spot the ambiguity relied upon by the dissenting justices. I have added the bolded highlight:

The governor may issue an executive order declaring a state of emergency for the state or any portion of the state if he or she determines that an emergency resulting from a disaster or the imminent threat of a disaster exists. If the governor determines that a public health emergency exists, he or she may issue an executive order declaring a state of emergency related to public health for the state or any portion of the state and may designate the department of health services as the lead state agency to respond to that emergency. If the governor determines that the emergency is related to computer or telecommunication systems, he or she may designate the department of administration as the lead agency to respond to that emergency. A state of emergency shall not exceed 60 days, unless the state of emergency is extended by joint resolution of the legislature. A copy of the executive order shall be filed with the secretary of state. The executive order may be revoked at the discretion of either the governor by executive order or the legislature by joint resolution.

This is a standard provision for states adopting the Model State Emergency Health Powers Act (“MSEHPA”). The 2002 model law was controversial due to the unilateral authority given to governors. I was one of those who wrote and opposed such provisions as dangerous concentrations of authority. That model law allowed governors to unilaterally renew such declarations — a provision that I and some others specifically criticized.

Wisconsin is one of the states the heeded the criticism and refused to adopt MSEHPA’s provision allowing for the public health emergency declaration to be unilaterally renewed every 30 days. MSEHPA § 405(b). Instead, it retained its prior time limitations on emergency orders. 2001 Wis. Act 109, § 340L.

The record therefore would seem abundantly clear in both its language and its statutory history. However, in dissent, Justice Ann Walsh Bradley wrote that the court should allow for a more fluid reading in light of the pandemic: “This is no run-of-the-mill case. We are in the midst of a worldwide pandemic … with the stakes so high, the majority not only arrives at erroneous conclusions, but it also obscures the consequence of its decision.” Bradley relies on the interpretation of a word “occurrence” that does not even appear in the operative provision while allowing the ends to drive the means on the interpretation. The dissenting justices adopt an artificial construct to claim that this is not one emergency but a series of ongoing emergencies even though they are all based on Covid-19. In this way, they suggest that a governor could just daisy-chain declarations by pretending that each insular pandemic concern is another emergency. Indeed, the worsening of a pandemic was viewed as a new “occurrence”:

Unlike Order #72, which was premised on preparing Wisconsin for the fight against COVID-19, Order #82 declared a new public health emergency in response to a “new and concerning spike in infections” that without quick intervention “will lead to unnecessary serious illness or death, overwhelm our healthcare system, prevent schools from fully reopening, and unnecessarily undermine economic stability . . . .” Order #82 detailed that “on June 1, 2020, there were 18,543 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Wisconsin; on July 1, 2020, there were 29,199 confirmed cases of COVID-19, a 57 percent increase from June 1; and on July 29, 2020, there were 51,049 confirmed cases of COVID-19, a 75 percent increase from July 1.” ¶118 Accordingly, Order #82 was issued in response to a specific and discrete occurrence.

That reasoning would effectively (and judicially) negate the express limitation of a 60-day rule under the law.

Rather than insisting on an objective and detached reading of the law, the dissenting justices repeatedly return to the specter of the pandemic and the need for a single figure in control: “the ultimate consequence of the majority’s decision is that it places yet another roadblock to an effective governmental response to COVID-19, further jeopardizing the health and lives of the people of Wisconsin.”

The dissenting opinion adopted an interpretative approach that allowed for a judicial reconstruction of the law to support the governor’s claim of sweeping authority. You can read the opinion for yourself but I found the dissenting opinion to be strikingly and dangerously detached from the express language of the law.

Here is the opinion: Fabick v. Evers

Reprinted with permission from JonthanTurley.org.