In his quest for front-runner status in the 2020 presidential campaign, Pete Buttigieg has crafted an image for himself as a maverick running against a broken establishment.

On the trail, he has invoked his distinction as the openly gay mayor of a de-industrialized Rust Belt town, as well as his experience as a Naval reserve intelligence officer who now claims to oppose “endless wars”. He insists that “there’s energy for an outsider like me,” promoting himself as “an unconventional candidate.”

When former Secretary of State John Kerry endorsed Joe Biden this December, Buttigieg went full maverick. “I have never been part of the Washington establishment,” he proclaimed, “and I recognize that there are relationships among senators who have been together on Capitol Hill as long as I’ve been alive and that is what it is.”

But a testy exchange between the South Bend mayor and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard during a November 20 Democratic primary debate had already complicated Buttigieg’s branding campaign.

Like Buttigieg, Gabbard was a military veteran of the 9/11 generation. But she had taken an entirely different set of lessons from her grueling stint in Iraq than “Mayor Pete.” Her campaign had become an anti-war crusade, with opposition to destructive regime change wars serving as her leitmotif.

After ticking off her foreign policy credentials, Gabbard turned to Buttigieg and lit into him for stating his willingness to send US troops to Mexico to crack down on drug cartels.

A visibly angry Buttigieg responded by accusing Gabbard of distorting his record, then quickly deflected to Syria, where he has argued for an indefinite deployment of occupying US troops.

Rehashing well-worn criticism of Gabbard for meeting with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad during a diplomatic visit she took – her trip was devoted to de-escalating the US-backed proxy war that had ravaged the country’s population – Buttigieg attacked the congresswoman for engaging with a “murderous dictator.”

Throughout the exchange, Buttigieg appeared shaken, as though his sense of inviolability had been punctured. Gabbard had clearly struck a vulnerable point by painting the self-styled outsider as a conventional DC-style politician unconsciously spouting interventionist bromides.

How could someone who served in the catastrophically wasteful US wars in the Middle East, and who had seen their human toll, be reckless enough to propose sending US troops to fight and possibly die in Mexico? “But Assad!” was the best response he could muster.

The remarkable dust-up highlighted a side of the 37-year-old political upstart that has been scarcely explored in mainstream US media accounts of his rise to prominence. It revealed the real Buttigieg as a neoliberal cadre whose future was carefully managed by the mandarins of the national security state since almost the moment that he graduated from Harvard University.

After college, the Democratic presidential hopeful took a gig with a strategic communications firm founded by a former Secretary of Defense who raked in contracts with the arms industry. He moved on to a fellowship at an influential DC think tank described by its founder as “a counterpart to the neoconservatives of the 1970s.” Today, Buttigieg sits on that think tank’s board of advisors alongside some of the country’s most accomplished military interventionists.

Buttigieg has reaped the rewards of his dedication to the Beltway playbook. He recently became the top recipient of donations from staff members of the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department, and the Justice Department – key cogs in the national security state’s permanent bureaucracy.

His Harvard social network has been a critical factor in his rise as well, with college buddies occupying key campaign roles as outside policy advisors and strategists. Among his closest friends from school is today the senior advisor of a specialized unit of the State Department focused on fomenting regime change abroad.

That friend, Nathaniel “Nat” Myers, was Buttigieg’s traveling partner on a trip to Somaliland, where the two buddies claimed to have been tourists in a July 2008 article they wrote for The New York Times.

Their contribution to the paper was not any typical travelogue detailing a whimsical safari. Instead, they composed a slick editorial that echoed the Somaliland government’s call for recognition from the US government. It was Buttigieg’s first foreign policy audition before a national audience.

A short, strange trip to Somaliland

Under public pressure for more transparency about his work at the notoriously secretive McKinsey consulting firm, the Buttigieg campaign released some background details this December. The disclosures included a timeline of his work for various clients that stated he “stepped away from the firm during the late summer and fall of 2008 to help full-time with a Democratic campaign for governor in Indiana.”

How Buttigieg’s “full-time” role on that gubernatorial campaign took him on a nearly 8,000-mile detour to Somaliland remains unclear.

Buttigieg and Nathaniel Myers spent only 24 hours in the autonomous region of Somaliland. In that short time, they interviewed unnamed government officials and faithfully relayed their pro-independence line back to the American public in a July 2008 op-ed in the New York Times.

The column read like it could have been crafted by a public relations firm on behalf of a government client. In one section, the two travelers wrote that “the people we met in Somaliland were welcoming, hopeful and bewildered by the absence of recognition from the West. They were frustrated to still be overlooked out of respect for the sovereignty of the failed state to their south.”

Since declaring its independence from Somalia in 1991, Somaliland has campaigned for recognition from the US, EU, and African Union. It even offered to hand its deep water port over to AFRICOM, the US military command structure on the African continent, in exchange for US acceptance of its sovereignty.

Several months after Buttigieg traveled to the autonomous region, Al Jazeera reported, “The Somaliland government is trying to charm its way to global recognition.”

And just a few weeks before Buttigieg’s visit, the would-be republic inked a contract with an international lobbying firm called Independent Diplomat, presumably to help oversee that charm offensive.

Founded by a self-described anarchist named Carne Ross, Independent Diplomat represents an array of non and para-state entities seeking recognition on the international stage. Ross’s client list has included the Syrian Opposition Coalition, which tried and failed to secure power through a Western-backed war against the Syrian government.

Independent Diplomat did not respond to questions from The Grayzone about whether it had any role in facilitating the trip Buttigieg and Myers took to Somaliland.

According to John Kiriakou, a former CIA case officer, ex-senior investigator for the Senate Intelligence Committee, and celebrated whistleblower, Somaliland is an unusual destination for tourism.

“There really is nothing going on in Somaliland,” Kiriakou told The Grayzone. “To say you go to Somaliland as a tourist is a joke to me. It’s not a war-torn area but nobody goes there as a tourist.”

Kiriakou visited Somaliland in 2009 as part of an investigation for the Senate Intelligence Committee on what he described as the phenomenon of “blue-eyed” American citizens converting to Islam, traveling to Somalia and Yemen for training with Salafi-jihadist groups, then returning home on their US passports.

To reach Somaliland, Kiriakou said he took an arduous seven-hour journey from the neighboring state of Djibouti. His junket was coordinated by the US ambassador to Djibouti, a regional security officer of the US Diplomatic Security Service, and an embassy attaché.

“It is not the easiest place to reach and there’s no business to do there,” Kiriakou said.

Whether or not Buttigieg’s trip was coordinated without the assistance of lobbyists, the trip offered him and Myers an opportunity to weigh in on international affairs on the pages of the supposed newspaper of record – and on an absolutely non-controversial issue.

In his bio, Nathaniel Myers identified himself simply as a “financial analyst based in Ethiopia.” According to his resume, which is available online at Linkedin, he was working at the time as a World Bank consultant on governance and corruption.

By 2011, Myers had moved on from that neoliberal international financial institution to a specialized government at the center of US regime change operations abroad.

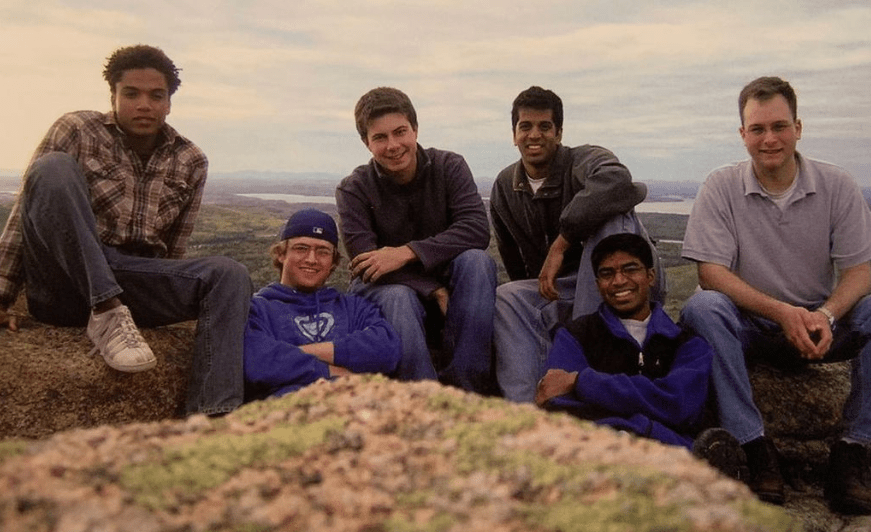

Pete Buttigieg on a pre-graduation trip with his Harvard buddies. Nathaniel “Nat” Myers is to his immediate left.

The imperial social network

Nathaniel Myers’ relationship with the presidential hopeful began at Harvard University. There, they formed two parts of “The Order of Kong,” a close-knit group of political junkies named jokingly for the Chinese restaurant they frequented after intensive discussion sessions at the school’s Institute of Politics.

Like most members of the college-era “Order,” Myers and Buttigieg have remained close. When the mayor married his longtime partner in 2018, Buttigieg chose him as his best man.

Myers currently works as a senior advisor for the United States Agency for International Development’s Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID-OTI) in Washington DC. The OTI is a specialized division of USAID that routinely works through contractors and local proxies to orchestrate destabilization operations inside countries considered insufficiently compliant to the dictates of Washington.

Wherever the US seeks regime change, it seems that USAID’s OTI is involved.

In a 2015 op-ed arguing for a loosening of bureaucratic restraints on USAID’s participation in counter-terror operations, Myers revealed that he had “specialized in programming in places like Yemen and Libya” – two conflict zones destabilized by US-led regime-change wars. (Myers was working as a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations at the time, but would return to USAID’s OTI the following year.)

USAID’s OTI has also fueled Syria’s brutal proxy war, coordinating US government assistance to supposed civil society groups like the White Helmets that were attached to the armed extremists who ruled over portions of the country for several years.

In Venezuela, the OTI has spent tens of millions of dollars cultivating and training opponents of the late President Hugo Chavez and his successor, Nicolas Maduro. It has done the same in Nicaragua, serving as the linchpin of a US effort to “lay the groundwork for insurrection.”

In Cuba, meanwhile, the OTI attempted to stir up civil unrest through a fake, Twitter-style social media site called ZunZuneo, hoping to turn the public against the country’s leftist government through coordinated flash mobs. To populate the phony social media platform, the OTI contracted a DC-based firm called Creative Associates that had illicitly obtained half a million Cuban cellphone numbers.

USAID and Creative Associates attempted to place ZunZuneo into private hands through a Miami foundation called Roots of Hope, which was founded by students at Harvard University. Twitter founder Jack Dorsey was even solicited by the State Department to operate the platform. (Roots of Hope board member Raul Moas, who personally trained ZunZuneo employees, is today the director of the Knight Foundation.)

The devious operation and its eventual exposure revealed the extent to which covert operations historically associated with the CIA had been outsourced to private contractors and NGOs.

And the role of the Harvard-founded “Roots of Hope” in the scheme demonstrated how much USAID and its contractors depended on the same Ivy League talent pool that produced Buttigieg and Myers.

A lengthy paper Myers authored for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 2015 indicated that he had special knowledge of the ZunZuneo scheme and had been invested in its success.

Myers took the journalists who exposed the USAID-OTI program to task, claiming that “individual grants were pulled out of context and described as failures without heed to their actual goals,” provoking an unfair “Capitol Hill pillorying.”

He lamented that the exposure of covert programs like these had forced USAID officials to pursue “the opposite of the programming most likely to produce real impact in a hard aid environment.” In other words, fear of public scrutiny had complicated efforts to subvert societies targeted by the US for regime change – and he didn’t like it one bit.

To Syracuse University professor of African American studies Horace Campbell, youthful cadres like Myers were a symptom of the American university’s transformation into a neoliberal training ground.

“Many idealistic graduates from elite centers such as the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, the Maxwell School of Citizenship of Syracuse University or the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University among others had been seduced” into careers with USAID contractors like Creative Associates, Chemonics, and McKinsey, Campbell lamented in a lengthy 2014 survey of the OTI’s sordid record.

“It has been painful,” the professor wrote, “to see the ways in which the so called NGO initiatives have been refined over the past twenty years to support neoliberalism and to depoliticize idealistic students.”

Campbell’s comments painted a clear portrait of Myers, who earned his master’s degree at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School on his way towards becoming a “hard aid” specialist at USAID.

They also captured the psychology of Buttigieg, who celebrated Bernie Sanders as a hero when he was a high school senior, and spoke out against the Iraq war as a Harvard junior before being absorbed into the culture of McKinsey and DC institutions like the Truman Center.

The Truman show

When Pete Buttigieg made his journey to Somaliland in 2008, he had just earned a fellowship at the Truman Center, a Washington-based think tank that provided a steppingstone for national security-minded whiz kids like him to leadership positions in the Democratic Party.

Buttigieg likely earned the fellowship after answering an ad like the one the Truman Center published on the website of the Harvard Law School Student Government in 2010. Soliciting applicants for its security fellowship, the center declared that it was seeking “exceptionally accomplished and dedicated men and women who share President Truman’s belief in muscular internationalism, and who believe that strong national security and strong liberal values are not antagonistic, but are two sides of the same coin.”

This was not the first time Buttigieg had dipped his toes into Washington’s national security swamp. After graduating from Harvard, he worked at the Cohen Group, a consulting firm founded by former Secretary of Defense William Cohen that maintained an extensive client list within the arms industry. (As The Grayzone reported, the Cohen Group has been intimately involved in the Trump administration’s bungling regime change attempt in Venezuela).

But it was Buttigieg’s fellowship at the Truman Center that placed him on the casting couch before the Democratic Party’s foreign policy mandarins.

A Tablet Magazine profile of Truman Center founder Rachel Kleinfeld described her as a “gatekeeper and ringleader” whose network of former fellows spanned Congress and the Obama administration’s National Security Council. Her career trajectory mirrored Buttigieg’s.

After last night, more proud than ever to support @PeteButtigieg – for those who missed it, a few reasons why: https://t.co/1XreWO5x15

— Rachel Kleinfeld (@RachelKleinfeld) October 16, 2019

She had earned degrees at elite institutions (Yale and Oxford, where Buttigieg pursued his Rhodes scholarship) before accepting a job at a private contractor, Booz Allen Hamilton, that performed an array of services for the US military and private spying for intelligence agencies.

Kleinfeld’s boss at the company was James Woolsey, the neoconservative former CIA director who has lobbied aggressively for US military assaults on Iraq and Iran.

According to Tablet, “Woolsey positioned Kleinfeld to work on sensitive government projects the company was pursuing in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks, including one that involved working as a researcher for the military’s Defense Science Board, investigating information-sharing between intelligence and law-enforcement agencies.”

When Kleinfeld founded her think tank in 2005, she named it for the president who oversaw the detonation of nuclear bombs on two Japanese cities, threats of another nuclear assault on North Korea and the killing of 20 percent of that country’s population. The Truman doctrine, which called for “containing” the Soviet Union through internal destabilization and relentless pressure on its periphery, was the basis of Washington’s Cold War policy. (Following Kleinfeld’s lead, Buttigieg named one of his two pet dogs Truman).

“We decided there really was a need to create a movement of Democrats to stand up for these ideas and to really start to think about it, very much as a counterpart to the neoconservatives of the 1970s,” she told the Forward at the time.

To fill the center’s board of advisors, Kleinfeld assembled a cast of Democratic foreign policy heavyweights whose accomplishments included the devastation of entire countries through regime change wars.

Among the most notable Truman advisors were Madeleine Albright, the author of NATO’s destruction of Yugoslavia and president of an influence-peddling operation known as the Albright Stonebridge Group; the late Council on Foreign Relations President Les Gelb, who once proposed dividing Iraq into three federal districts along sectarian lines; former Department of Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano, who oversaw record levels of migrant deportations; and Anne-Marie Slaughter, the former State Department Policy Planning Director who conceived the Responsibility To Protect (R2P) doctrine deployed by the Obama administration to justify NATO’s disastrous intervention in Libya and drum up another one against Syria.

“The Truman Project mobilizes Democrats who serve the conventional interventionist agenda,” journalist Kelly Vlahos wrote. “Beyond that, they are part of a broader orbit of not so dissimilar foot soldiers on the other side of the aisle.”

Buttigieg listed his fellowship at the Truman Center as one of the credentials that qualified him for Indiana State Treasurer when he ran for the position in 2010.

Though he lost in a landslide, Buttigieg won election as mayor of South Bend the following year. “Mayor Pete” had not only secured his future in the Democratic Party, he had won a place in its foreign policy pantheon with a seat on the Truman Center’s advisory board.

Balancing opposition to “endless wars” with support for new ones?

This July 11, Buttigieg rolled out his foreign policy platform in a carefully scripted appearance at Indiana University. Introduced by Lee Hamilton, a former Indiana congressman who was a fixture on the House Foreign Affairs and Intelligence Committees, Buttigieg blended a call to “end endless wars” with Cold War bluster directed at designated enemies.

Before an auditorium packed with the national press, he rattled off one of the more paranoid talking points of the Russiagate era, blaming President Vladimir Putin for fueling racism inside the US. He then attacked Trump for facilitating peace talks in Korea, slamming the president for exchanging “love letters” with “a brutal dictator,” referring to North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un.

You will not see me exchanging love letters on White House letterhead with a brutal dictator who starves and murders his own people @PeteButtigieg

— Rachel Kleinfeld (@RachelKleinfeld) June 11, 2019

More recently, Buttigieg’s campaign pledged to “balance our commitment to end endless wars with the recognition that total isolationism is self-defeating in the long run.” This was the sort of Beltway doublespeak that defined the legacy of Barack Obama, another youthful, self-styled outsider from the Midwest who campaigned on his opposition to the Iraq war, only to sign off on more calamitous wars in the Middle East after he entered the White House.

On the presidential campaign trail, “Mayor Pete” has done his best to paper over the instincts he inherited from his benefactors among the national security state. But as the campaign drags on, his interventionist tendencies are increasingly exposed. Having padded his resume in America’s longest and most futile wars, he may be poised to extend them for a new generation to fight.

Reprinted with permission from the Grayzone Project.

Support the Grayzone Project on Patreon.