DEFENSE PAPER: TAMING THE WARFARE STATE

The United States is sailing through turbulent waters: the post-Cold War unipolar moment has passed, and the 21st-century geopolitical landscape is shaped by sweeping social, political, and technological change. Our current defense policy, a relic from a bygone era, is an expensive and ill-fitting suit that no longer serves its purpose. The fiscal storm is upon us, and profound changes are needed to right the ship.

The Defense Elephant in the Room

The realization that the United States is in fiscal free fall is beginning to sink in. An economic crisis looms, one that bailouts and quantitative easing cannot stop. Regardless of the circumstances, profound changes in defense structure, leadership, and thinking are needed. These changes will inevitably evoke strong responses from Capitol Hill and the defense industry.

The incoming President has three choices:

1. Allow service bureaucracies or external events to drive outcomes, resulting in few or no savings. This is akin to letting the ship drift aimlessly, at the mercy of the storm.

2. Make marginal adjustments to the defense status quo, avoiding conflicts but achieving little change and only modest savings. This is like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic—it won’t save the ship.

3. Leverage the fiscal crisis to reduce overhead, streamline defense investment, and reset the force structure, increasing capability and promising major savings. This is the bold course correction needed to navigate the storm safely.

This paper argues for the third choice: leverage change to build new, better forces for the 21st century, allowing for deep spending cuts of \$400-500 billion. This approach enhances the U.S. military’s competitive advantage in future warfare and improves American national security by ending open-ended interventions without attainable political-military objectives. Assuming Congress acts wisely, the resulting annualized savings can both pay down the national debt and reorient U.S. military power to new forms of warfare.

Grand Strategy and New Thinking

Grand strategy, if it exists at all, consists of avoiding conflict, not starting wars. New thinking in defense and foreign policy prioritizes diplomacy and peaceful cooperation over military power. None of America’s potential opponents, except those with nuclear weapons, pose a direct threat to the American homeland. If international terrorism and criminality remain threats, then border security and tightly controlled immigration should be the top priority in national security.

Senior military leaders and their services cannot be expected to reform themselves and fundamentally change the military status quo—a World War II/Cold War structure that is expensive, single-service focused, and vulnerable to weapons of mass destruction. Peter Drucker, when asked how to change a large business enterprise, answered, “If you want something new, you must stop doing something old. People in any organization are always attached to the obsolete.”

In line with Drucker’s guidance, the incoming President must implement a new national military strategy that diverges sharply from the last 30 years. This strategy must scale back America’s forward presence, mandate adaptation to new forms of warfare, and address the requirement to retain and develop America’s best human capital in uniform.

Toward a New National Military Strategy

For real and meaningful reductions in the current $1 trillion national defense budget to occur, national command authorities must alter the nation’s strategic focus. New national security legislation must move the posture of U.S. forces away from military interventions focused on nation-building, democratization, or alleged threats. Instead, the defense posture should focus on the Western Hemisphere, learning to avoid patterns of behavior antithetical to U.S. interests.

The following five points offer the foundation for a new national military strategy that is both affordable and sustainable within the new multipolar, international system of the 21st century:

• Defend America First: Reserve the use of American military power for defense of the United States in the Western Hemisphere. Secure U.S. borders, coastal waters, and airspace. Military power may be used to defend American citizens and identified vital strategic interests at home and abroad. However, unless the United States’ vital strategic interests or territory are directly attacked, Washington will avoid the use of force.

• Maintain Strategic Military Power: Ensure U.S. freedom of action in areas of strategic importance by preserving and enhancing the American military’s core capabilities. Identify, defend, and maintain critical lines of communication and a reduced number of overseas bases needed for the execution of these tasks.

• Declare a “No First Use” Doctrine for Nuclear Weapons: Maintain the scientific-industrial capacity to wage high-end conventional warfare and build nuclear weapons, but recognize that the alleged advantage of striking first with nuclear weapons is illusory. Preventive or preemptive war is unwise and immoral and should be excluded from American military strategic planning.

• Establish an Operational National Defense Staff: Develop, update, and implement a refined Unified Command Plan to dramatically reduce unneeded overhead and improve the U.S. Armed Forces’ responsiveness to national command authority. This action requires legislation to place a “Chief of Defense” in the chain of command with real authority, not just advisory responsibility.

• Build New Armed Forces for the 21st Century: America needs a strong military designed to protect the United States in the 21st century, not an anachronistic and expensive industrial-age structure with enormous overhead and few fighters.

Trends in Force Design

Precision strike effects (kinetic and non-kinetic) using a vast array of weapons in all domains enabled by the rapid and timely dissemination of information through networked Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities point the way to a fundamental paradigm shift in 21st-century warfare. Russian military success in the recent war between Russia and Ukraine owes much of its success to the integration of many factors.

First, the mobilization of manpower, economic and industrial production. Second, Russian production of key weapons systems rose dramatically after October 2022, immediately after U.S. Commerce Secretary Raimondo told Congress that U.S. sanctions had reduced Russia to using semiconductors from “dishwashers & refrigerators” for their weapons. Third, Russian weapon systems performed beyond Western expectation. Western weapons did not. Washington and its allies infused Ukrainian Forces with equipment and technology on the scale of U.S. Lend Lease to the Soviet Union during WWII, but the weapon systems and equipment could not outpace Russian performance.

Finally, Russian commanders on the battlefield still had to direct their forces, tactics mattered, and the readiness of the Russian soldier to close with and destroy his opponent was critical to battlefield success. Russia’s decision to conduct a strategic defense in depth reduced the sensor-to-shooter time to the point that operational strikes using cruise missiles, glide bombs, rocket artillery, and tactical ballistic missiles were directed by brigade commanders against targets in minutes. What emerged was an ISR-Strike Complex that integrated maneuver and logistics across thousands of square miles to magnify the impact of Russian military power. In this operational setting, the defense triumphed over the offense.

Russian Integrated Air Defense Systems (IADS) shot down roughly 35,000 drones, 647 aircraft (all types), and 283 helicopters. Russia’s tight integration of ISR with Strike Weapon Systems (artillery, rockets, missiles, and aircraft-delivered bombs) is responsible for 870,000 casualties of an estimated 1.8+ million Ukrainian casualties. The numbers of Ukrainian dead probably exceed 600,000. Meanwhile, in less than three years of combat, the Russian military sustained 120,000 casualties, including 75,000 soldiers killed in action.

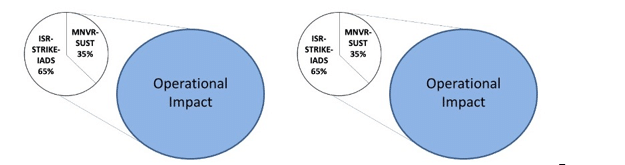

Open disbelief in the possibility that Russian ISR-Strike Complex could defeat masses of armor and aircraft resulted in repeated battlefield failures costing the lives of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers. The point is that ISR and Strike capabilities now shape mission areas that cut across all domains (land, sea, air, and space). Single-service command structures are obsolete. U.S. capabilities must be integrated within the ISR-Strike Complex at the operational level to detect, deter, disrupt, neutralize, or destroy opposing forces decisively. Much of the Ukrainian force that was destroyed resembled our force structures and equipment. This recognition demands a thorough analysis of our own forces, weapons, and employment norms from the standpoint of effectiveness and efficiency.

After WWII, Eisenhower said, “Separate ground, sea, and air warfare is gone forever.” The time to translate Eisenhower’s vision into reality is long overdue. Defense investments, commitments, and missions must be aligned with new forms of warfare that make traditional maneuvers on the battlefield extremely difficult, if not impossible. In other words, it’s time to optimize today’s forces within the trend lines shown below to guide strategic investment/acquisition over time.

Aligning defense investments with the evolutionary trends alters the traditional defense paradigm. Optimizing “capability at cost” inside the Post-Industrial Age structure dramatically increases the operational impact of each dollar spent. Failure to correct contemporary industrial age inefficiencies and duplications reduces operational impact and perpetuates unsustainable “cost exchange ratios” with opponents as seen in Ukraine.

In sports, getting to the ball is not enough. Winning teams move to where the ball is going to be; to where their players can pass the ball for a scoring shot. Teams win by identifying patterns in the game’s evolution, patterns they can leverage. Patterns are not absolute and adjustment to leverage the patterns is required on the way to victory.

Warfare is similar. Hindsight tells us that machine guns and artillery would kill millions of unprotected infantrymen during World War I. But hindsight could have been foresight if viewed through the right lens. In Clayton Christensen’s book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, the author argues that corporations should create specialized, autonomous organizations to exploit new technologies or risk squandering revolutionary capabilities inside status quo organizations. A special purpose organization designed to lead changes in defense is needed for the same purpose.

Persistent surveillance linked to modern Strike Weapon systems including tactical ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, rocket artillery, manned and unmanned systems of every kind make the conduct of traditional amphibious, airborne, or airmobile operations impossible in anything but permissive environments. Moving large ground forces, tracked or wheeled together with supporting logistical equipment, ammunition, food, and medical supplies with sea transport over the vast distances of the Pacific, Atlantic, or Indian Oceans is not viable in contested environments. Long-range precision Strike from submersible, surface, or land-based platforms dominate the battlespace. In other words, repeating any of these operations on the scale of WWII would be suicidal.

The implications for ground forces, Army and Marine, are significant. Until these ground forces can find ways to cope with this strategic environment, they should be reduced in size and reorganized. U.S. Army and Marine Corps missions must be reevaluated in the context of future needs and requirements. A modest amount of redundancy in capability can be helpful, but there is simply too much. It would make sense to shift most of the light infantry or motorized infantry missions to the Marines and shift high-end conventional warfare missions to the U.S. Army.

In the meantime, Army end strength and Marine end strength should be reduced to 430,000 and 120,000 respectively. The two services must be viewed as components of the larger ground force. Their roles and missions must be redefined by informed civilian leadership.

Thousands of Marines floating around the world waiting for a crisis to break out is wasteful. We should retain the capability to conduct amphibious operations and to evacuate Americans worldwide. But self-labeling USMC as America’s 911 force is a recipe to promote more relevance, funding, assets, and people that are not needed.

Marines and Soldiers already share equipment sets and train together in the Army’s school system and training centers. In the absence of a requirement to maintain large Marine forces in readiness to conduct amphibious operations, the two services need to conduct thorough roles and mission review since they are likely to operate together in the future.

Marine aviation is costly and difficult to maintain. Mandating the consolidation of Marine jet-driven manned aircraft with the Navy’s airwings would seem an obvious solution in a battlespace where future close air support missions are likely to be performed by unmanned systems.

The U.S. Navy confronts similar challenges. Fleets organized around large surface combatants like modern aircraft carriers are now easy to identify, target, disable, or sink. Submarines and unmanned submersibles are the foundation for American maritime dominance on the high seas, not a fleet on the Midway-Jutland model. Submarines rule the waves.

The incoming Secretary of Defense should direct the reduction of the Navy’s Surface Fleet to 8 Carrier Battle Groups (CVBGs) and rebalance home porting in response to new national priorities. Combatant commanders should also be instructed to reevaluate “presence versus surge” naval requirements given improved long‐range precision strike and ISR capabilities of smart presence alternatives.

Like the Marine Corps and the U.S. Army, the Navy and the Coast Guard are moving closer together in terms of mission profile and required capabilities. It makes sense to incorporate the U.S. Coast Guard into the U.S. Navy. If blended seamlessly, the two complement and reinforce one another.

Aerospace forces must also cope with new challenges. Integrated air and missile defenses are more capable now of identifying target forms regardless of aircraft design. These developments suggest alterations in modernization and force design priorities. Hundreds of manned bombers on the B-21 model are not affordable. Alternative platform solutions that are less expensive but still capable of delivering ordinance at high altitude must be found. To this point, the F-35 has proved to be a delicate wallflower that cannot withstand the rigors of practically any operational environment. The future Secretary of the Air Force must address this problem.

Clearly, the Service Secretaries will require flexibility to re-direct any identified savings. In other words, Service Secretaries will need to move money around to better align themselves with the new strategy. An example would involve reassigning Embassy Guards to light infantry formations, or re-investing savings into a future capability or infrastructure. The same applies to operational funding cuts.

Nuclear weapons remain unchanging necessities for national defense until some new breakthrough in technology renders them obsolete. The problem Americans confront is the tendency to think about nuclear war within an emotional framework that is grounded in the past. The rising lethality of individual warheads and the capability to deliver multiple warheads with a single missile system suggests that matching a potential opponent’s arsenal weapon for weapon makes no sense.

Americans should design the nuclear force by determining what is required to make a first strike suicidal for any nuclear power. Then, decide what is needed for that purpose to ensure launch reliability and national protection. Placing large numbers of nuclear weapons and warheads in the American Midwest, America’s breadbasket, should be reconsidered or even replaced by placing more weapons at sea.

Reducing Overhead

Today’s Senior Military Leaders and their forces are living within the organizational structure of the 1947 National Security Act; a paradigm for strategic military action rooted in the WWII experience. Reshaping the bloated warfare state to defend America first demands the elimination of wasteful and redundant single-service overhead and support structures. This is not a new problem.

During the 1944-45 advance from Normandy to the Rhine, General Montgomery’s headquarters controlled only two armies, which in turn had only two and three corps respectively, and the corps operated only two to three divisions—sometimes, even, only one. The ratio of headquarters was no more economic in the U.S. Army. B.H. Liddell Hart noted that the abundance of headquarters was one reason why the allied advance across the continent to Berlin was so protracted, despite plenty of transport and understrength German ground forces without air cover.

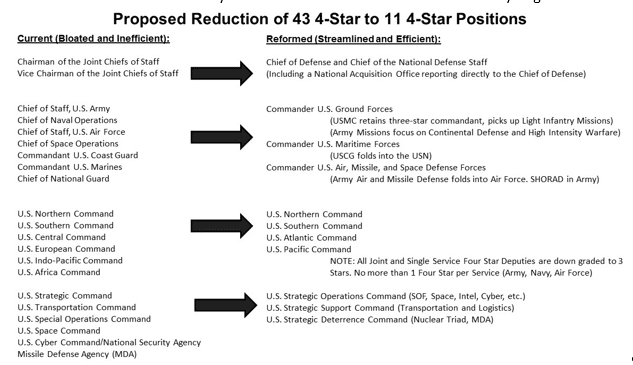

At the height of WWII when there were 12 million men in the United States Armed Forces, 7 four-star generals and admirals commanded them: Marshall, MacArthur, Eisenhower, Arnold, King, Nimitz, and Leahy.

How many four-stars are there currently commanding today’s Armed Forces? Answer: 43 four-star generals and admirals. In other words, the steady growth of headquarters at all echelons of command and control in the 80 years since WWII has worsened the tendency to grow overhead.

It is now painfully obvious that American fighting forces have declined in strength and numbers, but four-star overhead has grown out of all proportion to the nation’s security needs. Reducing the numbers of serving four-star generals and admirals along with their large and expensive headquarters is more vital than ever. In a perverse way, the expansion of general officer headquarters overhead follows Boyle’s gas law (also referred to as the Boyle–Mariotte law). When contained, gas will always expand to the limits of the container. So will headquarters and the flag officers they serve.

The point is to reduce, then replace the senior ranks. All appointments to three or four stars should be temporary with the understanding that the serving general officer will retire with the rank, benefits, and retired pay of a major general. This was the standard before WWII, and it should be reinstituted.

Another bureaucratic appendage worthy of attention is the Civil Service. We should keep talent within the force despite age or promotion by creating “talent spaces” that could still usefully employ experts rather than outsourcing them to contractors that charge exorbitant management fees for producing the same answers. This requires a close analysis of functions and purposes, and how it is paid for. The defense contractors thrive on providing studies and answers that are neither forward-thinking nor rigorous but designed to comfort the client and provide corporate welfare to retired senior officers.

As most of these positions would be middle to senior grade experience, the necessity of growing a large, parallel civil service at low levels to create seniors could be eliminated. The most ruthless analysis of Function and Purpose for each military and civil service job must be incorporated in any new force structure analysis.

In this connection, the illustration translates the observations in the previous section into reality. The Marine Corps now picks up the lion’s share of the light infantry missions currently assigned to the U.S. Army. The Army’s mission profile now includes continental defense and the readiness to fight medium to high-intensity warfare. The Navy and the Coast Guard are combined. Air, missile, and space defense missions are consolidated under one commander. The six functional unified commands are reorganized into three commands.

Joint Task Force (JTF) Headquarters are another critical step in the process of flattening command structures. Today’s single-service headquarters that populate the regional unified commands are given “Joint Plugs” and augmentation if the headquarters are selected to command forces from more than one service.

These JTFs are by design ad hoc and service centric. Current and future operations in the regional unified commands require a unified, integrated military command structure designed to employ dispersed forces across service lines as capability-based forces inside a Maneuver-Strike-ISR-Sustainment Complex. Integration within a relatively flat, joint command structure is a vital step in the direction of combining maneuver forces with Strike, ISR, and sustainment capabilities from all the Services.

In fact, why are there any single-service war colleges? In the aftermath of WWII, General Courtney Hodges, Commander, First Army, from August 1944 to May 1945, said, “It was imperative in future years, especially at the War College and at Leavenworth, that the officer be thoroughly trained in both ground and air operations so that logically by this system an air force officer could command a corps or an army.”

In this connection, it makes sense to disestablish Service Component Acquisition Executives. Combine these staff members under the Deputy Chief of Staff for Acquisition of the National Defense Staff and combine the new office with the Office of the Undersecretary for Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USDATL). This will abolish service‐centric acquisition autonomy.

The incoming Secretary of Defense should also direct the establishment of a 3-Star Joint Force Command (JFC) at Joint Base Lewis-McChord with the goal of building the template for standing headquarters to execute integrated operations across the new regional unified commands. How many of these operational Headquarters are needed is a subject for careful examination but is beyond the scope of this paper.

New Human Capital Strategy

Human capital requires time to build capacity and demonstrate value. Future Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines must be recruited to serve. In bad economic times, it is easier to attract talented people that are unable to find employment. In good times, relationships between the armed forces and the families that served in them are critical to maintaining adequate force levels. Handsome uniforms, reputations for fighting skills or status in a society that reveres its history and the martial virtues of courage, strength, sacrifice, and loyalty that were required to build and defend the society are all vitally important.

Reductions in the force always demand a new way to look at the Armed Forces’ Human Capital Strategy. In 1922, when the series of Civil Wars finally ended, Lenin, the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, made the decision to reduce the size of the Soviet Armed Forces from 5 million men to 600,000. His decision was not well received. Although Soviet Forces lost the war with Poland, the soldiers argued that they had defeated the many millions of domestic and foreign enemies trying to destroy the new Soviet State.

Millions of men felt betrayed, but Lenin recognized he needed to extract savings from the reductions that would later be used to industrialize the Soviet Economy. Lenin acknowledged the battlefield successes and losses, but Lenin concluded it was time to identify a pool of talented and intelligent officers with the knowledge and understanding to learn from the experiences of WWI and the Civil Wars, and to begin building the foundations for entirely new forces.

Conditions in postwar Germany were not much better, but it was clear that new forces would be needed in the future, forces with greater striking power, fundamentally new leadership, and new tactics. Many fine, exceptionally brave officers were released from active duty in favor of thoughtful, innovative general staff officers with adequate, but limited combat experience. The men retained in the postwar German Army of 100,000 would be the seed corn of future victories because the desired outcome involved new thinking about organizations, technology, and tactics.

Today, America’s armed forces confront a similar dilemma. The enormous downward pressure on defense spending exerted by a looming financial crisis, a faltering economy, social unrest, and a long string of failed military interventions in the Middle East are combining to make recruiting more difficult than ever. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs are making matters worse than ever. They should be terminated. Veterans who worry about the quality of senior military leadership are counseling young family members not to join up.

Integrity remains a serious problem. A congressman who participated in a hearing on mixed-sex training quipped, “You need to understand that these people are going to give you the answer they think you want, and these people are not going to run contrary to the Joint Chiefs.” The congressman said. Referring to a bipartisan commission appointed by the Clinton administration, the same congressman noted that in 1997 the services unanimously supported reverting to separate-sex training of recruits. The services cited a lack of discipline and physical rigor as the main justifications.

A fish rots from the head. If officers detect resistance to the truth in the senior ranks, then officers at lower levels will run silent or repeat the lie. Bureaucrats spend time trying to do the thing. Leaders do what is right. Spending political capital to end the travesty of mixed-sex training let alone the reform and reorganization of national defense, spending political capital should not be the only option. The Commander in Chief has a right to expect his military leaders to lead, not behave like politicians who spend their time chasing, rather than leading public opinion.

The perception is growing that character, competence, and intelligence are irrelevant to promotion systems rigged to reward demonstrated political fidelity to ideological viewpoints that are either harmful to morale and discipline or simply fatuous. Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, or Marines are far more interested in justice, the performance of duty, and devotion to the country than in abstract gender-focused politics or social science concepts. They expect to be rewarded based on merit, not racial, sexual, or political identity.

As the force grows smaller, the standards of performance, mental and physical fitness should rise, not fall. No one who is unfit to deploy should be retained on active duty. To the extent that it can be done, the National Guard and Reserve should mirror the Active Force. Whenever possible, retired or disabled veterans should fill administrative posts on military reservations.

What should be done to rectify what’s wrong? First, if forces must become smaller, they should also become better. There is no point in recruiting substandard people. Recruiting must become more personal and permanent, stationing of specific units near or where the recruits live must be considered. Enlisted ranks and warrant officers should be able to invest in housing near the locations where the formations in which they serve are permanently stationed.

All formations/ships/airwings should have identified home garrisons to which they return after completing deployments. Officer careers will be subject to a different set of expectations given career development demands, but other ranks and their families must be given a more stable life. Reserve and National Guard units should, if possible, partner with active-duty units. When Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, or Marines leave the force, they should be encouraged to join the Guard and Reserve partner units. These relations must be cultivated and strengthened. When a crisis or conflict occurs, active-duty units will inevitably have openings that partner units can help fill.

For every three years of honorable service, service members should receive one year of exemption from Federal and State Taxes regardless of the length of time they serve. 9 years provides 3 years of tax-free living. 21 years of service provides 7 years of freedom from State and Federal taxation. This policy should incentivize Americans with the desire to build businesses to serve for a minimum of three years to receive one tax-free year.

Given the unstructured nature of modern warfare, it is almost certain that military operations will develop in unforeseen ways. This is true on the tactical, operational, and strategic levels. This means that future commanders must be trained to do more than obey. They must exercise initiative and think through the consequences of their actions, whether they are told specifically what to do in varying circumstances. The deficit we should worry most about is intellectual, not fiscal. The incoming Administration must nourish a core group of military professionals who are competent to cope with the unexpected when it arises.

There is also the question of youth. Major General J.F.C. Fuller noted, “The more elastic a man’s mind is… the more it is able to receive and digest new impressions and experiences… Youth, in every way, is not only more elastic, but less cautious and far more energetic.” It is no accident that the average age of a full colonel commanding an infantry regiment in the WWII Army was 35 years.

A New Human Capital Strategy for the military must value talent more than longevity. Eliminating unneeded echelons of command offers the opportunity to promote younger, exceptional officers faster to flag rank.

The Service Academies have strayed far from their original purposes. Today, the academies are nothing more than Universities where the boys and girls wear uniforms. The question today is why the American Taxpayer should offer a tuition-free four-year college education and degree to someone who is appointed to a Service Academy? It’s time to ask whether the early 19th Century four-year Cadet School is the best or even the right way to prepare Americans for their professional military duty of leading Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, or Marines into action?

Conclusions

Compelling change in U.S. national defense is tantamount to war. Bold, new initiatives can succeed. Moving to the point of least resistance leads to failure and no change. There is no time to lose. The Department of Defense is cannibalizing itself to meet operational demands, and, in the process, we are getting older faster and destroying our most precious resource—human capital. Bold changes are necessary now.

If the American People are ever to rectify the abysmal record of the American military in action in the last three decades, shrink, then replace the senior ranks. Change in organization and culture will not result in streamlined unified military command structures and more fighting power without new senior military leadership. Modern warfare will demand much more than PowerPoint slides or dominating weak opponents with overwhelming firepower.

During his presidency, Eisenhower’s goal was to “achieve both security and solvency.”

The developing fiscal crisis creates the opportunity for Washington to both economize and develop the Nation’s range of strategic options in military affairs. Unfortunately, Washington’s decisions since 1991 to employ military power were often made without an accurate and sobering self-assessment of America’s strengths and its weaknesses.

Without a new national strategy and new senior military leaders in place, the senior leaders of the armed forces will simply shrink existing forces until more money and people are provided to restore them to their original size. This is a dead end. Compared with the last war, the next war is frequently virgin territory.

Given his experience during WWII, Eisenhower was very hard on service parochialism. Realizing that the service chiefs viewed themselves as first being accountable first and foremost to their own service, he insisted that the Service Secretaries stand firmly behind the Eisenhower administration’s defense program, even though it might not fully meet any one service’s desires.

In 2025, new national leadership must provide the American People with solutions that are effective and sustainable. President Eisenhower’s 1958 prescription is still a good guide for the future: “The purpose is clear. It is safety with solvency. The country is entitled to both.”