When Americans vote each four years, they are not directly electing a president. Instead, under the United States Constitution, each state, as well as the District of Columbia (DC), appoints to the Electoral College a number of electors that equals the sum of the state’s allotted senators and representatives in Congress, or three electors for DC. These electors then vote. Win a majority of electors’ votes and you become president.

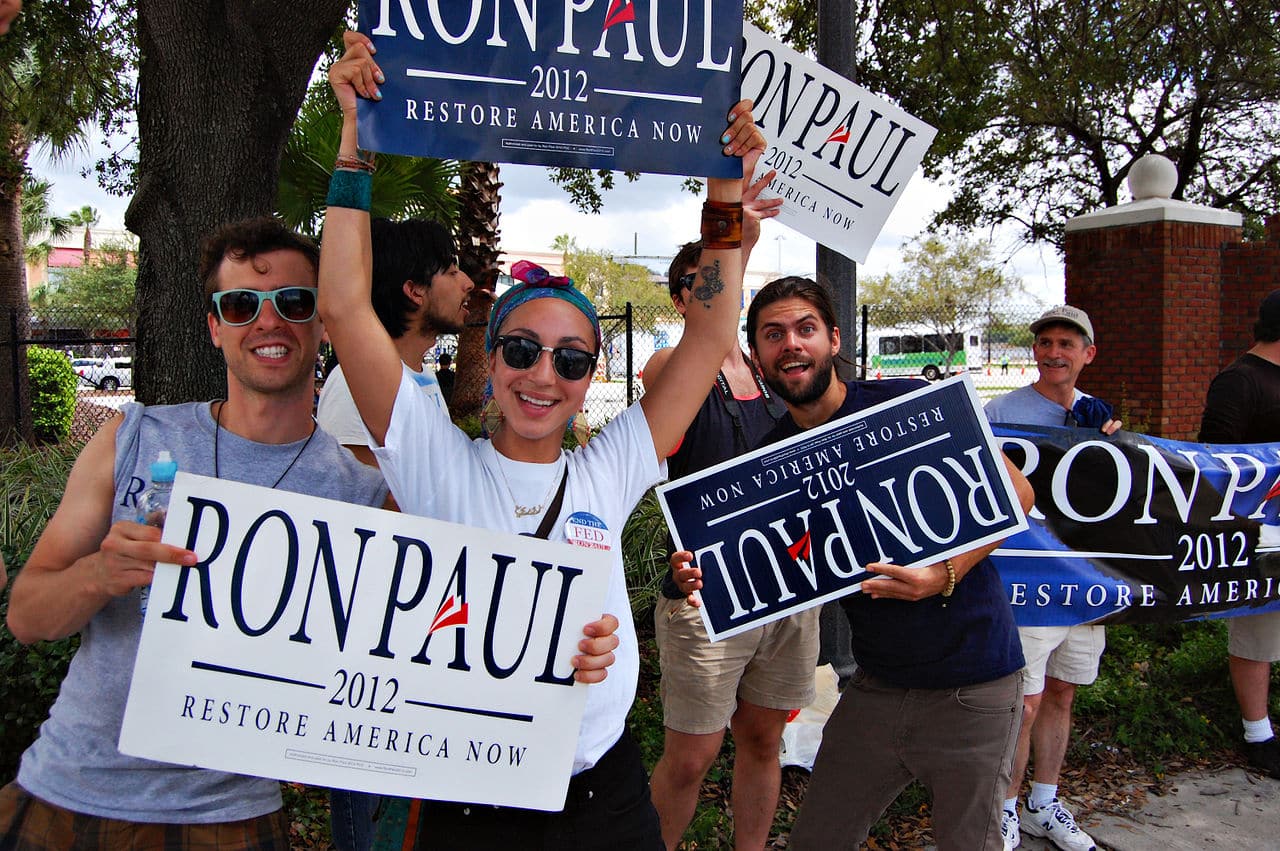

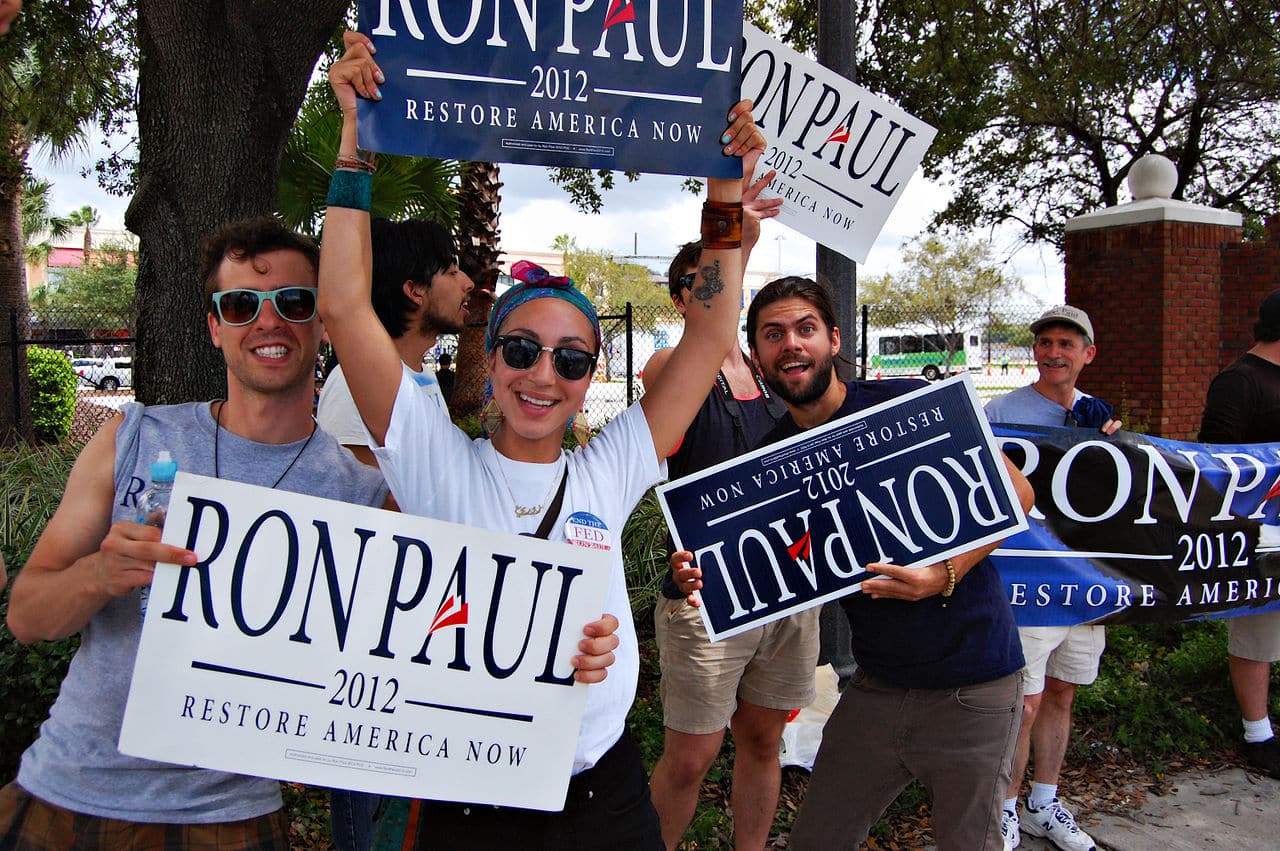

Typically, electors vote for who won the popular vote in their respective states. In fact, the process in most states is for a state to send to the Electoral College a slate of electors who have pledged to vote for the candidate who won the popular election statewide. But, sometimes electors want to vote for someone else. Kyle Cheney reported Thursday at Politico that in 2012 three of the 38 total Texas electors — all pledged to support Republican nominee Mitt Romney — suggested instead that they might vote for Rep. Ron Paul (R-TX) who had run against Romney in the Republican presidential nomination contest:

Steve Munisteri, former chairman of the Texas GOP and the 2012 leader of Texas’ Electoral College delegation, said it’s not uncommon for electors to hint at rejecting their party’s nominee. He said three Texas Republican electors in 2012 suggested they might vote for Ron Paul instead of Mitt Romney. But when reminded of oaths they took when running for the position, all of them eventually cast their ballots for Romney.

How many other electors from across America may have similarly contemplated casting their votes for Paul? Ultimately, though, none followed through on such thoughts. The 2012 Electoral College voting results included presidential votes for only President Barack Obama and Romney.

Yet, sometimes electors do vote contrary to the popular vote totals in their states. One example of this occurred in the 1972 presidential election when the John Hospers and Tonie Nathan presidential ticket of the newly formed Libertarian Party received a vote in the Electoral College despite winning less than 5,000 popular votes and being on the ballot in only two states. Roger MacBride, an elector from Virginia (one of the vast majority of states in which the Libertarian presidential ticket was not on the ballot), cast that vote. Four years later, MacBride was the Libertarian presidential nominee. While MacBride’s ticket was on the ballot in the majority of states and garnered well over 150,000 popular votes, it won neither any elector votes nor a victory in any state’s popular vote.