I’ve been reading The New Jacobinism: America as Revolutionary State by Claes G. Ryn, first published in 1991. It’s a short but insightful polemic about the pernicious influence of neoconservatism—the “New Jacobinism”—on American affairs. Here is a brief overview:

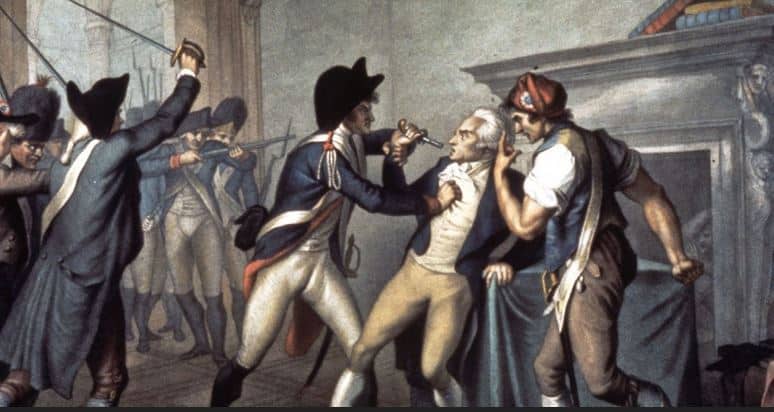

This strongly and lucidly argued book gave early warning of a political-intellectual movement that was spreading in the universities, media, think-tanks, and foreign-policy and national security establishment of the United States. That movement claims that America represents universal principles and should establish armed global hegemony. Claes G. Ryn demonstrates that, although this ideology is often called “conservative” or “neoconservative,” it has more in common with the radical Jacobin ideology of the French Revolution of 1789. The French Jacobins selected France as savior of the world. The new Jacobins have anointed the United States. The author explains that the new Jacobinism manifests a precipitous decline of American civilization and that it poses a serious threat to traditional American constitutionalism and liberty. The book’s analyses and predictions have proved almost eerily prophetic.

“Prophetic,” indeed, for two reasons.

First, it was published a decade before “President George W. Bush made neo-Jacobin ideology the basis of US foreign policy,” transforming America into the spearhead of the “global democratic revolution” with all the blood and tears that has entailed. Second, Ryn’s close encounter with neoconservatism helps to make sense of certain intellectual trends today.

The first wave of neoconservatives were liberals and anti-Stalinist leftists who defected to the camp of American conservatism in the 1960s and 1970s. In time, they would exert tremendous influence over the movement, most notably—or notoriously—by championing a hawkish foreign policy, which Ryn describes as neo-Jacobin. Key figures in the early days included Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz, both of whose waddling spawn might be their most heinous crimes.

Another important, albeit adjacent figure, is Allan Bloom, author of the 1987 bestseller, The Closing of the American Mind. As a critique of the academic left, it impressed conservatives then and remains a key text today. Ryn, however, immediately noticed serious red flags.

To be sure, Bloom insisted he was “not a conservative—neo or paleo.” Nevertheless, his polemic against left-wing intellectual trends was essentially an early articulation of neoconservatism, its pages being marked with the discrediting of tradition and history that characterizes the movement. Ryn was one of the few people who understood its real meaning.

A sign of the great and growing influence of the intellectual and political movement of concern to me was the enormous attention paid to The Closing of the American Mind by Allan Bloom (1930-1992). . . . . To many, Bloom’s book appeared to offer a conservative philosophy of education, but, to me, it seemed to require no special powers of discernment to recognize that, on the whole, the book was really a defense of the Enlightenment mind, which Bloom rather loosely and arbitrarily identified with the American mind. This was the mind whose “closing” he bemoaned. His book exhibited just the intellectual pattern of discrediting history and tradition that has been discussed. . . . Bloom sought to detach Americans from their distinctive historically evolved heritage, formed by classical, Christian, and British tradition. America was great not because of what that history had made it, but because America was founded on universally valid principles that belonged to all humanity.

For Bloom, as with the neoconservatives, America is chiefly an idea rather than a real place and product of a unique history and particular people. And it is this abstraction that provides the theoretical basis for “exporting” the “American idea” by force to the world—at the expense of flesh and blood Americans. This view reaches its apogee in Bill Kristol’s suggestion that “lazy” pockets of the white working class should be replaced with “new Americans.” To be an American, after all, is merely to subscribe to an idea composed of a vague set of principles simple enough to stuff in a Happy Meal and distribute to illegal aliens as they cross the border.

With these points in mind, Ryn was invited to contribute to a symposium in Modern Age on Bloom’s bestseller the year it was published.

I did not consider the book philosophically weighty or otherwise impressive; the huge attention that it was receiving was not due to its intrinsic merit but to its appealing to a large and growing part of the opinion-molding establishment. The celebration of Bloom was symptomatic of the intellectual trends of the time. Bloom did not escape criticism, but he had a large and extensive cheering section. . . . [Bloom’s book] contained ideas that were hard to reconcile with central features of the Western heritage, including the American political tradition. Many read it carelessly and selectively, paying attention primarily to its criticism of intellectually placid students addicted to drugs and bad music, of sycophantic, trendy professors, and of cowardly academic administrators. But only in these limited ways and only as compared to the extreme radicalism that the book criticized might the book appear to have a conservative aspect.

To Bloom, “the essence of philosophy was the rejection of historically formed beliefs and the abolition of all authority in favor of reason.” That kind of thinking tended in the direction of ideological uniformity, toward a Rousseauian totalitarianism.

But it was the next part of Ryn’s account that really caught my eye, because it gets at the “why” that helps explain the warm reception Bloom’s otherwise radical book received among conservatives.

To the extent that my article [in Modern Age] was noticed, purported conservatives seemed merely puzzled or to regard me as a spoilsport. Why question this celebrated critic of leftist trends in education? In one way I was not surprised by this reaction. Intellectuals are much like other people: most are followers who find reasons to assent at the moment. It was also obvious that the forces lionizing Bloom were capable of rewarding sympathizers.

In short, the right was willing to overlook Bloom’s radicalism because it had been easily wooed by celebrity—by the cachet of a prominent someone who had said some of what they had been saying about the left, despite fundamental and, indeed, irreconcilable differences. Ryn took it as a sign of neoconservatism’s ideological ascendancy, propelled by striving social climbers and sympathizers. Ironically, praise for his critique came from what was at the time developing into the “premier neoconservative think tank,” the American Enterprise Institute.

AEI had sought to boost its academic reputation by attracting distinguished scholars. Perhaps most prominent was Robert Nisbet, formerly the Schweitzer Professor at Columbia. But Nisbet obviously did not fit in very well. He called my article on Bloom “a superb indictment” and wrote me twice about it. He said, “Your review of Bloom is by far the best I have seen.” Later he added, “It pins [Bloom’s] Rousseauism/totalitarianism right to the wall. . . . Thank you!”

Still, the neoconservative force with which Bloom has been associated would influence the right profoundly.

I see the same tendency alive and well today among many conservatives who are eager to celebrate “disruptors” they perceive as having social capital or access to new social scenes, like Bari Weiss and others. Every quasi-dissenter is embraced with open arms by conservatives who are eager to compromise to accommodate their new friends—a relationship that is rarely reciprocal.

Too many conservatives are never happier than when garbled variations of right-wing points are mouthed on “Real Time with Bill Maher” by those who consider genuine conservatism the refuge of rubes and reprobates. Never mind that they often attack these positions before embracing qualified and sanitized versions of them.

But what else might explain this curious weakness on the right? Perhaps it is a confusion that arises from the fracas, a cloudy distortion of where and what the center is today. If the left has effectively achieved cultural hegemony in this country, which it has, then the cultural “center” is not midway between right and left but left of center. Take Weiss, who facilitated an attack on yours truly by British neoconservative Douglas Murray.

Like her anti-Stalinist predecessors, Weiss has broken with the “woke” left. But does that make her an ally to the right? Peruse National Review’s coverage of Weiss, and you’ll get that impression. Indeed, a recent piece in the magazine lionized her and boosted Senator Tim Scott—one of the worst Republicans on issues like law and order—against the New York Times. There is one sure loser in a fight between Weiss-Scott and the Times: the right.

A week before that article in National Review, Weiss’ publication ran a story by Peter Meijer, a moderate Republican, complaining about the Democratic Party’s funding of his “far-right” opponent. Democrats supported John Gibbs, who is to Meijer’s right, because they hoped Gibbs might be easier to defeat come midterms. Gibbs ultimately beat Meijer. But more to the point: Weiss has wasted no time since “leaving the left” to start policing the boundaries of the right. Because Weiss has not fundamentally moved, she simply pines for a stage in the revolution that suits her comfort level better.

As Trotskyites, those who would become the first neoconservatives wanted to spread “socialism.” After their transformation, the missionary impulse remained and switched to promoting “capitalism” and “democracy,” but as Ryn notes: “Capitalism, though cruel, was, in Marx’s view, a highly progressive force” because it undermines old traditions and social structures all the same. Similarly, people like Weiss yearn merely for a liberalism that served as the precursor to the woke ideology they now condemn.

Here is an illustrative lament from a typical Weiss reader commenting “on the ideological takeover of Hollywood” by wokeness:

I have been running the Oscar website AwardsDaily.com since 1999. I was one of the leaders pushing for inclusion and diversity starting back in 2001 when Halle Berry became the first black actress (and since, only black actress) to win in the category. It is hard to overstate just how hard it it [sic] was for actors, writers and directors to penetrate the white wall. I felt it was my moral duty to change that. But then Trump was elected. Then the community and the left became locked in a kind of mass hysteria.

The author goes on to decry the Democratic Party for exploiting identity politics and blasts “outrage culture” for stifling the arts.

Utterly absent, however, is any reflection on the role people like her and Weiss played in bringing us to this point—on their making the “explosion of woke” a certainty when they fashioned dynamite out of “inclusion and diversity” to knock down the “white wall.” Don’t they see that they helped set the stage for this moment? Woke ideology is not an aberration born of hysteria as these people pretend; it is the violent resolution of liberalism’s contradictions, the gunshot that ends the tension between individualism on the one hand and social justice on the other.

The real enemy, moreover, is still the reactionary, who reaches the height of his villainy in holding woke “McCarthy trials,” as the commentor puts it. But McCarthy was the good guy, as any genuine rightist knows.

The conservative insists that an alliance and compromise with these neo-Jacobins is necessary to win the culture war. Access to their audiences justifies the cost because we can “red pill” them. But that, of course, is incorrect. People who thought the main problem with Hollywood until recently was white racism are never going to come around to the right’s point of view, no matter how uncomfortable they are with the left for the moment. And while the conservative is willing to be amenable to change, these castaways are not. Instead, they become more tribal and territorial, convinced that holding the (left-of-) “center” places them on the right side of history.

My takeaway from Ryn’s gloss on the rise of neoconservatism is that the right should strive to be more jealous of its camp. It should want to be as ruthless as neoconservatives in exerting their influence and as willful as the left in asserting its vision. What it shouldn’t be is a refuge for yesterday’s radicals who are frightened by the monsters and maladies they helped create.

Reprinted with permission from Contra.

Subscribe to Contra here.