FBI agents across the nation are tracking down and arresting Trump supporters who walked into the US Capitol during the January 6 protest that turned into a brawl. Scores of protestors have already been charged with unlawful entry—“knowingly entering or remaining in a restricted building or grounds without lawful authority.” The media is treating this as a heinous and self-evident offense, but my own experience at Washington protests makes me wary of treating transgressions as treason.

I roamed downtown Washington on the day before the inauguration. The city was a ghost town, and most of the stores were either boarded up or out of business. More than a dozen subway stops were barricaded shut to prevent any guys wearing furry hats with horns from suddenly appearing from underground to strike terror into the hearts of the media.

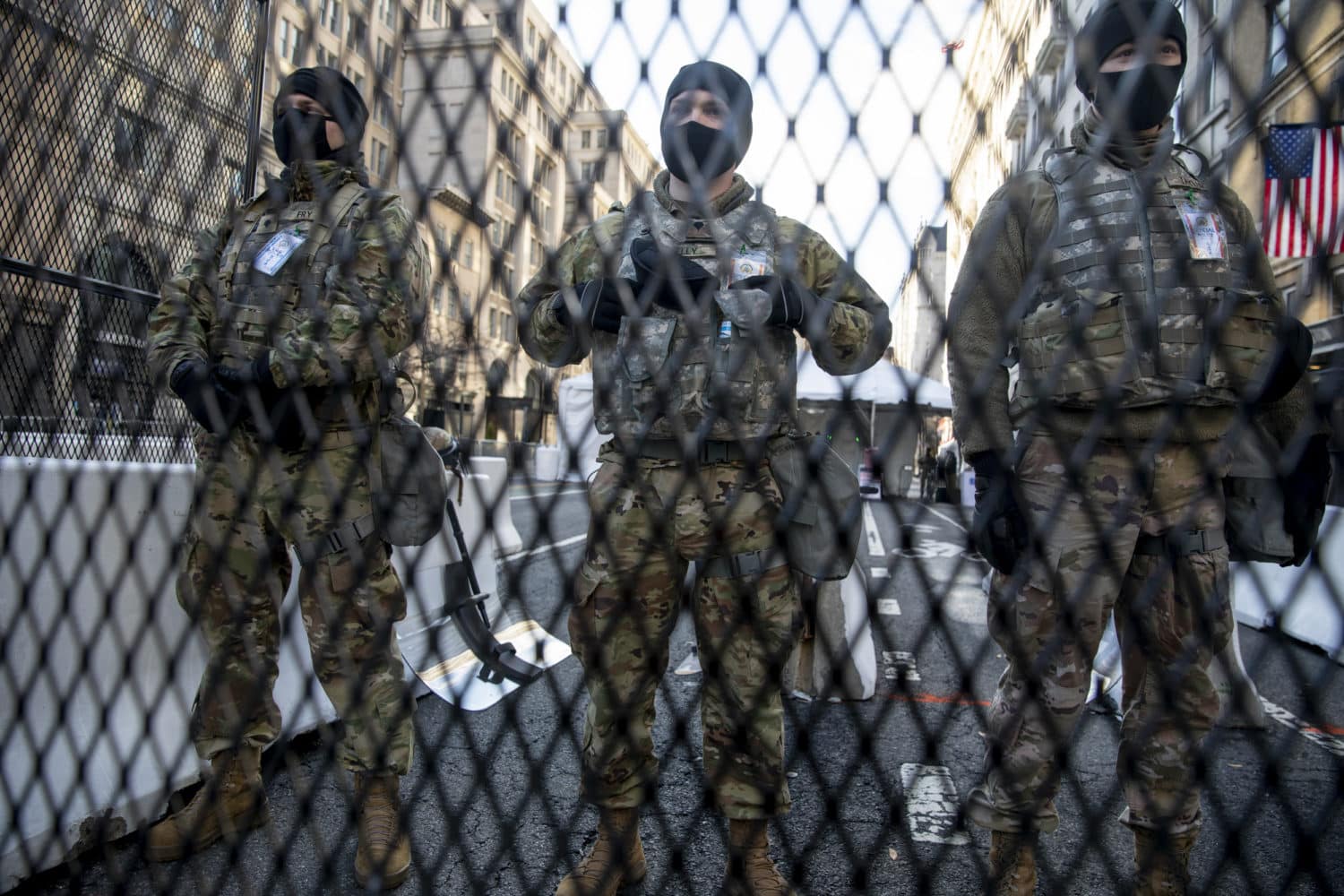

Practically the only folks on the streets were National Guard troops touting automatic weapons (mostly without ammo magazines). There were snipers on rooftops and helicopters occasionally buzzing overhead—all part of what DC mayor Muriel Bowser hailed as the “peaceful transition of power in our country.” If it had been even more “peaceful,” drones would have been blowing up manhole covers. Deploying twenty thousand troops in the nation’s capital was noncontroversial for the nation’s media, because the soldiers were supposedly protecting America against right-wing extremists.

At Farragut Square, I entered the “green zone”—the official term for the area the military locked down and the same term the US military used earlier in Baghdad. I ambled over to the edge of Lafayette Park next to the White House, scene of clashes between demonstrators and police last June and a Trump photo op that went awry. I have witnessed many rowdy protests at this park over the decades, but it was walled off with thick wire fencing. I could see the forms of soldiers on the other side of the barrier but not much else. No chance of getting even a glimpse of the White House.

I chatted with a Secret Service policeman guarding the entrance to the park. When I said I was heading toward the Mall, he replied: “You can’t go through here but if you go down to the next block—Seventeenth Street—you can walk to Constitution Avenue from there.”

I thanked the dude and made tracks. But after walking a block or two on Seventeenth, further progress was barred by a tangle of high barriers.

I saw a solitary soldier standing guard to make sure that no pickpockets carted off one of the four thousand–pound concrete jersey barriers blocking the road. He told me that if I went one block over, to Eighteenth Street, that was clear all the way to the Mall.

At Constitution Avenue, I saw that the Mall was completely barricaded. On the other side of the high fences, I saw troops patrolling with their rifles at the ready in case anyone tried to kidnap the geese in the Reflecting Pool.

In the distance, I could see the Washington Monument, but that was as close as I could get—that landmark was protected by row after row of barricades, from the edge of Constitution Avenue onward. To justify writing off my subway fare as a business expense, I took a bevy of bad photos, including a few with a large yellow Police Line Do Not Cross sign juxtaposed with the base of the monument.

Heading back up Eighteenth Street, I ran into another military roadblock—a half dozen soldiers staked out by a closed subway station. I told them I was looking to get to Dupont Circle. A young soldier with a heavy Southern accent replied, “You can’t go this away. The road is closed at the end of this block.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. I’m just following orders. You can go over to the next block—Seventeenth Street—and go up on that road.”

I tipped my hat to the dude and ambled along. There was no rhyme or reason to the street closures—just a long series of arbitrary edicts.

A pack of Metropolitan Police bicyclists suddenly came up the street. There was a slight incline in the road, so the cops were struggling like Tour de France riders crossing the highest peak in the French Alps.

As I watched their arduous ascent, I flashed back to fifteen years earlier when I had roamed the same street on my road bike while hundreds of thousands of marchers protested the Bush administration’s Iraq War. That event was well organized, with plenty of activist lawyers stationed along the route with cameras to document if the police used any brutality on the peaceful demonstrators. I had walked my bike with the marchers as they passed the Treasury building on the east side of the White House, where I snapped my all-time favorite photo of a glassy-eyed cop.

After hoofing for a mile with the protestors, I hopped on my bike, zipped down the street between Lafayette Park and the White House and then swung down Seventeenth Street on the west side of the White House. That road was almost empty except for two cops standing in the middle twenty-five yards ahead of me. As I got closer to them, a fat cop suddenly raised his four-foot wooden pole over his head and began moving directly into my path.

I was puzzled until I heard the other cop mumbling about how I wasn’t allowed on that street. His partner was getting ready to bust his stick over my head.

I revved up my speed, veered to the right, and laughed at the flatfoot over my shoulder. The street closing was not marked, but cops were still entitled to assail any violators—as long as there was no one around to film the beating. Actually, if that cop had smashed me with that pole, I might have been arrested on ginned-up charges such as assaulting a policeman. In the same way that cops routinely justify shooting motorists by claiming the driver was trying to run them down, so the pole dude might have claimed I was trying to run him over.

This struck me as a microcosm of what American society is becoming—more and more government agents waiting to whack anyone who violates a secret, unannounced rule.

I rode around the area to the west of the White House and, hearing some speakers in the distance, swung down another street toward the Ellipse in front of the White House. As I reached the intersection with Seventeenth Street, a gnarly police commander with a burning cigar butt clenched between his teeth screamed at me: “How did you get here!?!”

“I rode down the street,” I replied.

“You’re not allowed to come down on this street!”

“I didn’t see any signs or anything prohibiting it,” I said.

“I had two policemen at the entrance of the street,” he raged. “How did you sneak by them?”

I said I hadn’t seen anyone.

The cop boss was tottering on the edge of arresting me. Another policeman, dressed in civvies, suggested to this cigar chomper that he just let me go through the opening of the metal sawhorses.

Not a chance. The boss cop insisted that I reverse course and ride back down that street. I did so and, at the end of that block, I saw four DC police officers lounging in the shade, talking and laughing among themselves. Regardless of his subordinates’ negligence, the police commander took great satisfaction in reversing one bicyclist’s path. Maybe he even reported it as an “antiterrorism success” to superiors that day.

What the hell, I avoided getting thumped that day. But the flashback made me think of the plight of the hundreds of protestors who entered the Capitol on January 6 and now are facing legal ruin or long prison sentences.

In the past few weeks, the media and Democratic politicians have caterwauled that the clash at the Capitol was an attempted coup, putsch, or “insurrection” (the preferred label in the House of Representatives’s impeachment of Trump). A small number of participants assaulted police and did serious property damage. But most of the protestors entered the Capitol through open doors and wreaked no havoc once they had crossed the threshold. Videos show Capitol policemen doing nothing to impede legions of protestors who often stayed inside the designated rope lines for visitors. As American Conservative founder Pat Buchanan noted, “Had it been [A]ntifa or BLM that carried out the invasion, not one statue would have been left standing in Statuary Hall.” Many of the participants said they didn’t realize they were prohibited from entering the Capitol, and the vast majority left peacefully after a brief visit.

Most Americans support vigorous prosecution of protestors who physically assaulted police at the Capitol. But partly because of the thundering chorus that all participants were guilty of treason, and partly because of Democrats’ and media allies’ howling about the Capitol being “holy” and a “temple,” peaceful protestors also face legal ruin and possibly long jail sentences. The Washington Post reported, “Authorities say they could ultimately arrest hundreds, building some of their cases with the social media posts and live streams of alleged participants who triumphantly broadcast images of the mob.”

Federal prosecutors may pile “seditious conspiracy” charges atop the “unlawful entry” offense, threatening protestors with twenty-year prison sentences. Overcharging is routinely done by the feds to browbeat guilty pleas from people who cannot afford thousands of dollars in legal fees to prove their innocence. But the Justice Department may be realizing that many of its cases against the roughly eight hundred protestors who entered the Capitol could explode in the government’s face. Most of the 135 people charged thus far have no criminal records, and many are former military. The Washington Post noted on Saturday that…

…some federal officials have argued internally that those people who are known only to have committed unlawful entry—and were not engaged in violent, threatening or destructive behavior—should not be charged….Other agents and prosecutors have pushed back against that suggestion, arguing that it is important to send a forceful message that the kind of political violence and mayhem on display Jan. 6 needs to be punished to the full extent of the law.

One federal law enforcement official commented, “If an old man says all he did was walk in and no one tried to stop him, and he walked out and no one tried to stop him, and that’s all we know about what he did, that’s a case we may not win.” If the cases are all tried in Washington, then that would mean that the DC federal court would have to handle almost three times as many criminal cases as its total caseload for 2020. The Post noted that top officials are keenly aware that “the credibility of the Justice Department and the FBI are at stake in such decisions” on prosecuting protestors. It will take only a few cases against protestors to be squashed by jury nonguilty verdicts to severely damage the histrionic sedition storyline of the January 6 clash.

Americans who hanker to legally impale peaceful Capitol protestors should pause to recognize that far more turf in this nation may soon be permanently off limits to private citizens. DC Mayor Bowser warned that after the inauguration, “We are going to go back to a new normal. I think our entire country is going to have to deal with…a very real and present threat to our nation.” Some members of Congress favor turning Capitol Hill into the equivalent of a supermax prison, permanently surrounding the area with a high fence with razor wire. House speaker Nancy Pelosi says every day on Capitol Hill should be a “national security event.” Will that mean TSA-style checkpoints with far more pointless prodding of anyone who deigns to step onto federal grounds? The George W. Bush administration was notorious for decreeing vast “restricted zones” around the president when he traveled around the nation. Anyone who protested or even held up a critical sign in those areas could face arrest and federal prosecution. That type of repression could be revived by Biden, who was notorious for his dreadful record on civil liberties when he was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

In a free society, peaceful citizens deserve the legal benefit of the doubt. In an age where government agents have endlessly intruded onto people’s land and into their emails, citizens should not be scourged for transgressing unknown or unmarked federal boundaries. There are enough real criminals in this nation that federal prosecutors don’t need to seek publicity by destroying people who may have unknowingly illicitly violated politicians’ sacred turf.

Reprinted with permission from Mises.org.