Last September a very informative paper was published by the neoconservative Atlantic Council. In connection with this institution are such important public figures as Collin Powell, Condoleezza Rice and Henry Kissinger. The paper, written by John T. Watts, summarizes the main conclusions drawn at this year’s Sovereign Challenges Conference in Washington, DC. The text allows for a deep look into some of the minds of the American elite and their allies. Its reading is therefore highly recommended. The inclined reader, however, should sometimes overlook empty phrases and distracting rhetoric to get to the heart of the matter.

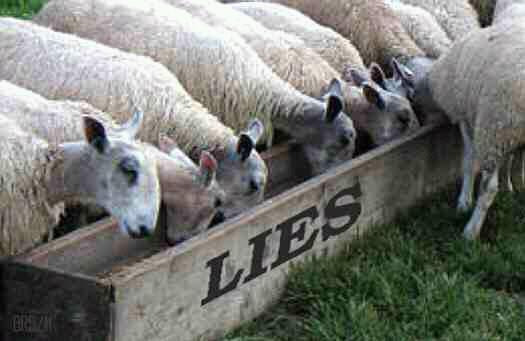

At its core, it’s about maintaining power. According to Watts, the big problem is “disinformation”, which is disseminated through new and alternative media. It destabilizes public institutions and in the worst case undermines the sovereignty of the state. This must be prevented.

Neoconservatives are fully aware that any state system ultimately depends on the trust of its citizens. Trust is the basis for the functioning of state institutions. New communication technologies, however, have increasingly enabled “extremist ideological” currents to spread their toxic messages and deprive people of confidence in existing institutions. It is precisely this loss of trust on the part of citizens that endangers the sovereignty of the state.1

The flood of information in the Internet age plays a decisive role because it makes targeted “disinformation” by small but well-organized groups possible in the first place. It leads to exaggeration, isolation and one-sidedness within one’s own “echo chamber”. According to Watts, the sudden availability of large amounts of information can overburden a society. Too much useless and qualitatively inferior information can lead to isolation and polarization. People specifically select their sources of information and limit themselves in the process. They even have to do so in view of the many alternatives available to them. But in doing so, they tend to rely on those sources that confirm and reinforce their own prejudices.

In order to underline the potential seriousness of the situation, Watts refers to Nate Silver’s book The Signal and the Noise, in which a parallel is drawn between the invention of the printing press and the advent of the Internet. This analogy was also taken up by the Scottish historian Niall Ferguson in his recent book The Square and the Tower.2 Both authors recall that the invention of printing not only made Luther’s Reformation of the Christian Church possible, but also provided a powerful means of communication for many populist and, from today’s point of view, deterrent movements. Here, for example, one can refer to the witch hunts of the early modern period. After Luther’s Reformation, Europe was also plunged into centuries of religious wars. Is something similar threatening us today in the age of the Internet? It is clear that also today existing hierarchies and power structures are questioned and start to falter. This usually leads to the old elites giving their all in order to maintain their privileged position.

But first it has to be clarified who is really behind the specter of “disinformation”. Watts refers not only to all sorts of “conspiracy theorists” like “truthers,” “chemtrailers” or “anti-vaxxers”, whose political and social impact can really be doubted, but also to Islamic terror groups or the Russian secret service, which is said to have influenced the outcome of the American presidential elections through such powerful social networks as Facebook.

At this point, however, we should pause for a moment. Is interference in the political affairs of other countries an exclusively Russian phenomenon? No. This has always been the case everywhere, especially on the part of the USA in recent history. So, if the Russian secret service is behind targeted disinformation, can the American establishment really free itself from it? Here, too, a clear no. Think, for example, of the deliberate manipulation of public opinion before various military interventions in the Middle East.

For Watts it is simply about which narrative dominates and determines public opinion. Truth is an elastic term, he claims. The question is merely: “Whose truth?” So, it is nothing but a power struggle. From this point of view disinformation is merely a truth deviating from one’s own truth and must be fought against. One’s own truth becomes the disinformation of the opponent. Therefore, according to Watts, new gatekeepers are needed in the modern flow of information. The prevailing opinion must be brought back on track.

The good thing, however, is that Watts is wrong. Truth is not subjective. It is, if at all, very limited in elasticity. And if it turns out that the hitherto so dominant narrative of the American establishment has overstretched the truth at one point or another, it is a blessing that modern communication technology makes it possible to point this out critically and effectively. We can only hope that technology will always stay one step ahead of regulators and gatekeepers – and that citizens will ultimately trust the narrative that is closest to the truth.

—

1. The loss of trust is reflected, for example, in this year’s Edelman Trust Barometer: Global Report. Interestingly, India, for example, has a higher trust index than the USA.

2. The interested reader is referred to Dr. David Gordon’s review of Ferguson’s book.

Reprinted with permission from LewRockwell.com.