Edward Snowden, the admitted U.S. National Security Agency whistleblower, is charged with violations of the U.S. Espionage Act of 1917, codified under Chapter 37, “Espionage and Censorship.” It is seemingly not an oversight that Chapter 37 is entitled “Espionage and Censorship,” as censorship is the effect, in part, of this chapter.

In fact, the amendment of §793 that added subsection (e) was part of the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950, which was, in turn, Title I of the Internal Security Act of 1950. In addition, these statutes were initially passed as the U.S. was entering World War I, with what was called the Sedition Act of 1918 added as amendments to the Espionage Act in short order.

They were codifications into federal law of what had been put into practice during the previous major war the U.S. fought, its own Civil War, codifying such martial law offenses as “corresponding with” or “aiding” the enemy by such acts as “mail carrying across the lines.” [See 1880 JAG Digest, W. Winthrop, attached to Prosecutors Brief.]

During the Civil War, draconian and extra-constitutional means had been used to suppress dissenting speech with the use of military commissions to enforce martial law and to punish any act, to include speech, that was deemed disloyal.

As a disclaimer, this isn’t to demonize President Abraham Lincoln or to sympathize with the Confederate cause. The South’s system of slavery, along with the slavery that still existed in parts of the North, was the epitome of tyranny, with totalitarian martial law applied to every single slave under the legal regime which had been created. But here the intent is to show how great a threat it is to free speech and a free press to use legal cases from that period as precedent for what the U.S. government is doing in the military commissions today.

This Civil War-era repression of free speech and the press, though unconstitutional under the First Amendment, was justified under the pretense of the “law of war,” falling under the President’s “war powers.”

Lieber’s Code of 1863 – or General Order No. 100 – was the first codification of the law of war and was named after the German-American jurist Francis Lieber. With all its virtues of more humanitarian treatment of prisoners of war, it was foremost a martial law regulation, as the first section addresses, establishing the authority of the military over civilians and declaring what acts constituted offenses.

But as the Supreme Court stated in the 1866 case, Ex Parte Milligan, “for strictly there is no such thing as martial law; it is martial rule; that is to say, the will of the commanding officer, and nothing more, nothing less.” [See Ex Parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2, 35 (1866)]

After the Civil War, so repudiated were those extra-constitutional practices – i.e., decrees by a president – that they weren’t resorted to again when the U.S. entered World War I, although the same passions were ignited in 1917. Yet, instead of executive decree implementing martial law, repressive laws were passed legislatively as the U.S. Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918.

But as the enforcement of these laws became evermore repressive, resulting in the McCarthyism of the 1950s, U.S. Courts began rolling back the suppression of speech, culminating with the 1969 Supreme Court decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio. In Brandenburg, it was held that speech could only be forbidden or proscribed, even if it advocates the use of force, “except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” [See Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444, 447 (1969).]

When ‘Everything Changed’

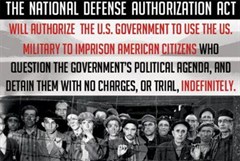

But with the attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001, military commissions were once again established by Executive Order invoking the “law of war.” Congress later ratified this substitution of military authority for civil authority with the Military Commission Acts of 2006 and then 2009, and expanded the authority even further with Section 1021 of the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act.

But beginning with the charges when the first Military Commission convened, vague offenses of “material support for terrorism” and conspiracy were claimed to be “war crimes” triable by military commissions. These were offenses that were analogized to “aiding the enemy” by Military Commission prosecutors. However, “aiding the enemy,” as interpreted during the Civil War, could be mere criticism of government officials, such as “publicly expressing hostility to the U.S. government,” according to documents filed by Military Commission prosecutors.

Under a strict reading of Section 793(e) of the Espionage Act, it is conceivable that the U.S. government, if it so chose, could prosecute any publisher, journalist, blogger or anyone else who may pass on classified information such as by forwarding a news article with WikiLeaks information in it. The over-classification of this information thus serves to censor the very sort of information necessary for a functioning democracy; what our government does in our name, whether embarrassing or not.

And, while prosecution under a federal statute would entitle a defendant to the due process rights of the U.S. Constitution, under military commissions, there is only the barest due process required, with a chimerical “right” to habeas corpus. So this parallel body of “law” – outside the Constitution and international treaties guaranteeing a free press and free speech – should be chilling to journalists and other communicators of political information, especially since the U.S. government asserts that prosecutions under U.S. military commissions apply globally.

Applying Civil War Precedents

This body of law is what Military Commissions Chief Prosecutor Mark Martins terms the “U.S. common law of war.” [See Brief for Respondent at 54, Al Bahlul v. United States (D.C. Cir.)(No. 11-1324).] With the exception of a couple of spying cases, this so-called “U.S. common law of war” is entirely drawn from the martial law cases of the Civil War, all in U.S. territory – Union states, not Confederate.

In making this argument, U.S. Military Commission prosecutors have argued that “it has long been clear that a class of wartime offenses exists that national authorities may criminalize and punish as a matter of domestic law.” This disingenuously ignores that these are only “offenses” when they are committed within the national territory of the authorities criminalizing them – thus the term “domestic” – and when the “offender” is captured in that same territory.

Military Commission prosecutors argue, however, that this “U.S. common law of war” is available to them in the prosecution of anyone regardless of where the alleged offense or the capture took place.

This colossal claim of universal jurisdiction by the U.S. military, using as precedent offenses that were acts of disloyalty in Union territory for the most part, raises the very real possibility that any global dissent to U.S. policy – by journalists, bloggers or political activists – can in the future be seen as violations of the “U.S. common law of war.”

This has the potential for any journalist – whether from a close ally, such as Great Britain, or from a “third-class partner,” such as Germany – to be subject to U.S. military arrest for any role they may have had in “communicating” U.S. classified information or anyone who may further disseminate it.

Using the Civil War offenses as precedents, this could also include offenses such as “publicly expressing hostility to the U.S. government,” which in fact was an offense cited by Brig. Gen. Martins as part of a list of offenses from the 19th Century JAG Digest to support his current proposition for the existence of a “U.S. common law of war.”

Totalitarian Foundation

To fully understand the totalitarian foundation of what is being called the “U.S. common law of war” – and noting the “law of war” was also the basis of “law” under such regimes as the German Nazis, the Soviet Union and Pinochet’s Chile – it is necessary to look at the original Civil War sources.

Brig. Gen. Martins’s Civil War predecessor in an equivalent position was William Whiting, Solicitor General of the War Department. He compiled what was a “legal guide” for Union Army Commanders, entitled “Military Arrests in Time of War,” and then expanded that to “War Powers Under the Constitution of the United States.” The guide was printed as one volume in 1864 as a compilation of opinions previously issued by the War Department.

In this legal guide, Whiting outlined and justified why it was necessary for civilians in the North to be subject to military arrest if their acts should in any way cause them to be the “enemy,” not just to “aid the enemy,” and what offenses those acts would be constituted as under the law of war, or martial law.

To be clear on terms, Whiting explained, “Martial Law is the Law of War.” Or, as General Henry W. Halleck, an acknowledged international law expert at the time of the Civil War, wrote in his treatise on international law. “Martial law, which is built upon no settled principles, but is entirely arbitrary in its decisions is in truth and reality no law, but something indulged rather than allowed as a law.” [See Henry W. Halleck, Vol. 1, Halleck’s International Law or Rules Regulating the Intercourse of States in Peace or War 501 (1878)(1st Ed. 1861).]

This understanding of the law of war, or martial law, was echoed by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Johnson Field, when he wrote in 1878: “It may be true, also, that on the actual theatre of military operations what is termed martial law, but which would be better called martial rule, for it is little else than the will of the commanding general, applies to all persons, whether in the military service or civilians. . . . The ordinary laws of the land are there superseded by the laws of war.” [See Beckwith v. Bean, 98 U.S. 266, 293-294 (1878).]

But Justice Field added, “This martial rule – in other words, this will of the commanding general … is limited to the field of military operations. In a country not hostile, at a distance from the movements of the army, where they cannot be immediately and directly interfered with, and the courts are open, it has no existence.”

Worldwide Battlefield

Today, however, U.S. government officials routinely describe the whole world as the battlefield, with seemingly the global population subject to the “U.S. common law of war,” as interpreted under the Civil War precedents, meaning President Lincoln’s Martial Law Proclamation of Sept. 24, 1862.

This read, in pertinent part: “ all Rebels and Insurgents, their aiders and abettors within the United States, and all persons . . . guilty of any disloyal practice, affording aid and comfort to Rebels against the authority of the United States, shall be subject to martial law and liable to trial and punishment by Courts Martial or Military Commission.”

An 1862 U.S. Army Order is quoted at the embarkation point for Alcatraz: “The order of the President [Abraham Lincoln] suspending the writ of habeas corpus and directing the arrest of all persons guilty of disloyal practices will be rigidly enforced.”

Disloyal practices were not limited to actual acts of rebellion but could be an offense such as any of the following: unauthorized correspondence with the enemy; mail carrying across the lines; and publicly expressing hostility to the U.S. government or sympathy with the enemy. [See William Winthrop, A Digest of Opinions of The Judge Advocate General of the Army 328-29 (1880).]

As readily apparent, those offenses go to the core of freedom of expression, as guaranteed under the U.S. First Amendment and internationally under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. But according to 19th Century “law of war” expert Col. William Winthrop, these were “offences against the laws and usages of war.” They were charged generally as “Violations of the laws of war,” or by their specific name or descriptions. [See William Winthrop, Military Law and Precedents 1314 (2d ed. 1920).]

These particular offenses for which civilians were tried by military commissions would have been committed in Union territory, as the population of the Confederate states was given belligerent rights and thus did not have the “duty of loyalty” as did civilians in the North.

The most prominent civilian tried and convicted by military commission was Clement Vallandigham, a former Ohio congressman and a member of the Democratic Party who supported the right of states to secede. In 1863, he was charged with “having expressed sympathies for those in arms against the Government of the United States, and for having uttered . . . disloyal sentiments and opinions.” [See Ex Parte Vallandigham, 68 U.S. 243, 244 (1863).]

But Vallandigham was only one of hundreds convicted for disloyal speech. Today’s Military Commissions prosecutors cite the 1862 case of editor Edmund J. Ellis to support their position that material support for terrorism is a “war crime,” even though it involved only disloyal speech from a newspaper editor convicted of violating the laws of war by publishing information “intended and designed to comfort the enemy.” [See Special Order No. 160, HQ, Dep’t of the Missouri (Feb. 24, 1862), 1 OR ser. II, at 453-57, cited in Bahlul v. U.S., Government brief at 48.]

That might be the same “offense” as the editors of the Guardian and Der Spiegel would be charged with under the so-called “U.S. common law of war.”

Defining a Violation

What is a law of war violation? During the Civil War, the War Department’s Solicitor General William Whiting provided a definition for the martial law that the U.S. was under:

“Military crimes, or crimes of war, include all acts of hostility to the country, to the government, or to any department or officer thereof; to the army or navy, or to any person employed therein: provided that such acts of hostility have the effect of opposing, embarrassing, defeating, or even of interfering with our military or naval operations in carrying on the war, or of aiding, encouraging, or supporting the enemy.” (Emphasis added.)

But as the United States has adopted these Civil War military commissions as precedents, the U.S. government logically has adopted this domestic martial law definition as well for the U.S. military to apply globally. And, as Whiting explained, military arrests may be made for the punishment or prevention of military crimes. [See William Whiting, War Powers under the Constitution of the United State 188 (1864).]

As Whiting stated, “the true principle is this: the military commander has the power, in time of war, to arrest and detain all persons who, being at large he has reasonable cause to believe will impede or endanger the military operations of the country.”

He elaborated further: “The true test of liability to arrest is, therefore, not alone the guilt or innocence of the party; not alone the neighborhood or distance from the places where battles are impending; not alone whether he is engaged in active hostilities; but whether his being at large will actually tend to impede, embarrass or hinder the bona fide military operations in creating, organizing, maintaining, and most effectually using the military forces of the country.” (Emphasis in original).

“Aiding the enemy” is, in fact, what constitutes the entirety of what Whiting describes as crimes of war. While it exists under martial law as described by Whiting, it is also codified under the U.S. Uniform Code of Military Justice as Article 104.

In either case, it was never contemplated that it criminalized anyone who didn’t have a “duty” of loyalty to the United States by being resident within the United States, until the U.S. government adopted an expansive interpretation of it in order to charge non-U.S. citizens with Material Support for Terrorism under the fallacious claim that the two offenses are analogous.

Talking to the ‘Enemy’

Under Article 104, Aiding the Enemy is defined as, in pertinent part, any person who: “(2) without proper authority, . . . gives intelligence to or communicates or corresponds with or holds any intercourse with the enemy, either directly or indirectly; shall suffer death or such other punishment as a court-martial or military commission may direct.” (Emphasis added.)

Article 99 is referenced for the definition of “enemy,” which defines enemy as the organized forces of the enemy in time of war and includes civilians as well as members of military organizations. In addition, Article 99 states: “‘Enemy’ is not restricted to the enemy government or its armed forces. All the citizens of one belligerent are enemies of the government and all the citizens of the other.”

Article 104c(6) explains the offense of “Communicating with the enemy” further: “No unauthorized communication, correspondence, or intercourse with the enemy is permissible. The intent, content, and method of the communication, correspondence, or intercourse are immaterial. No response or receipt by the enemy is required. The offense is complete the moment the communication, correspondence, or intercourse issues from the accused. The communication, correspondence, or intercourse may be conveyed directly or indirectly.” (Emphasis added.)

But this strict rule of non-intercourse, the term used during the Civil War era which strictly prohibits any “communication” with the “enemy,” is what provides the elements of “war treason,” as was frequently charged in the Civil War.

‘War Treason’

Article 90 of Lieber’s Code provided: “A traitor under the law of war, or a war-traitor, is a person in a place or district under Martial Law who, unauthorized by the military commander, gives information of any kind to the enemy, or holds intercourse with him.”

As war-traitors are the enemy also, as Solicitor General Whiting wrote, then any communication with a war-traitor – as the editor of the Guardian could be defined under the “U.S. common law of war” – would also be communication with the enemy, at least under this theory.

This is the foundation of totalitarian law, as we saw in the former Soviet Union and in Nazi Germany. In fact, both those regimes relied on military courts to strictly enforce loyalty by punishing “disloyalty,” war-treason, severely.

Germany under the Nazis even had a dedicated court, the National Socialist People’s Court, or Volksgerichthof (VGH), strictly for the prosecution of disloyal internal “enemies,” to include “non-German ‘terrorists’ in occupied France, Belgium, Norway and Holland, who were deported to Germany to stand trial in the VGH courts.” The court’s motto was; “Those not with me are against me.” [See H.W. Koch, In the Name of the Volk – Political Justice in Hitler’s Germany, 5 (1989).]

This isn’t to analogize the United States to totalitarian regimes, though German officials are currently likening the U.S. NSA surveillance program to the tactics of the Stasi. But it is to point out that the body of law that is the so-called “U.S. common law of war” has the same underlying legal theory as totalitarian bodies of “law,” and represents a threat to the global free flow of information and freedom of expression.

In the digital age, it is impossible to avoid “communicating” with the enemies of the United States as everyone on the planet has digital access to the Internet. Nations can no longer cut the telegraph lines to enemy territory to prevent communication, nor can a journalist limit his or her global digital audience.

Consequently, the “U.S. common law of war” hangs like the sword of Damocles over the global exercise of freedom of speech, of the press and of conscience. It is held in abeyance only at the sufferance of the U.S. president, but it could be allowed to fall at the start any new crisis.

As Lt. Col. Ralph Peters, U.S. Army (Ret.) wrote in 2009, “Although it seems unthinkable now, future wars may require censorship, news blackouts and, ultimately, military attacks on the partisan media.” [See Ralph Peters, Wishful Thinking and Indecisive Wars, The Journal of International Security Affairs, Spring 2009, www.securityaffairs.org/issues/2009/16/peters.php.]

Todd E. Pierce retired as a Major in the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General (JAG) Corps in November 2012. His most recent assignment was defense counsel in the Office of Chief Defense Counsel, Office of Military Commissions. In the course of that assignment, he researched and reviewed the complete records of military commissions held during the Civil War and stored at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Republished with author’s permission.

Image: Voltairenet.