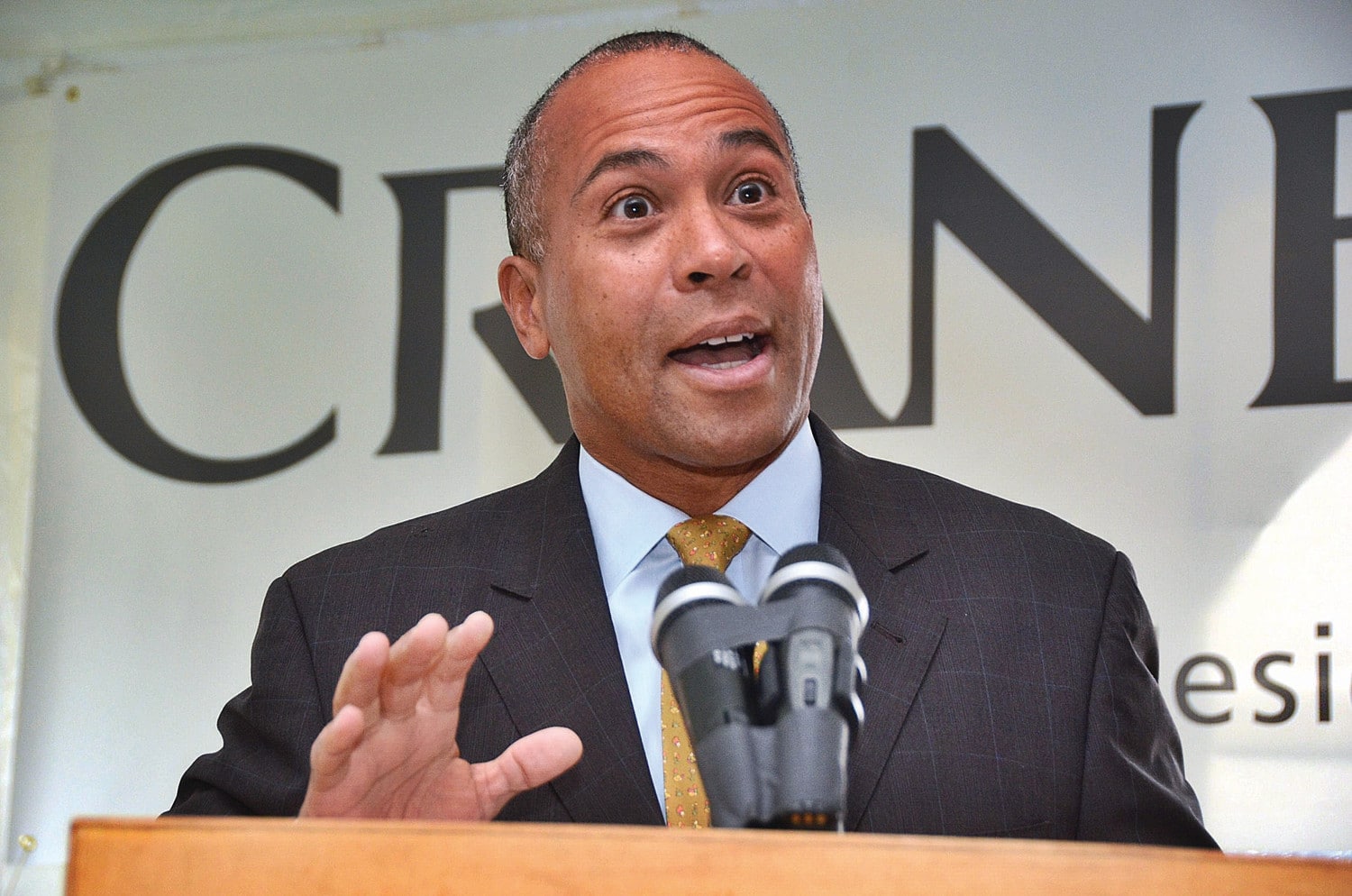

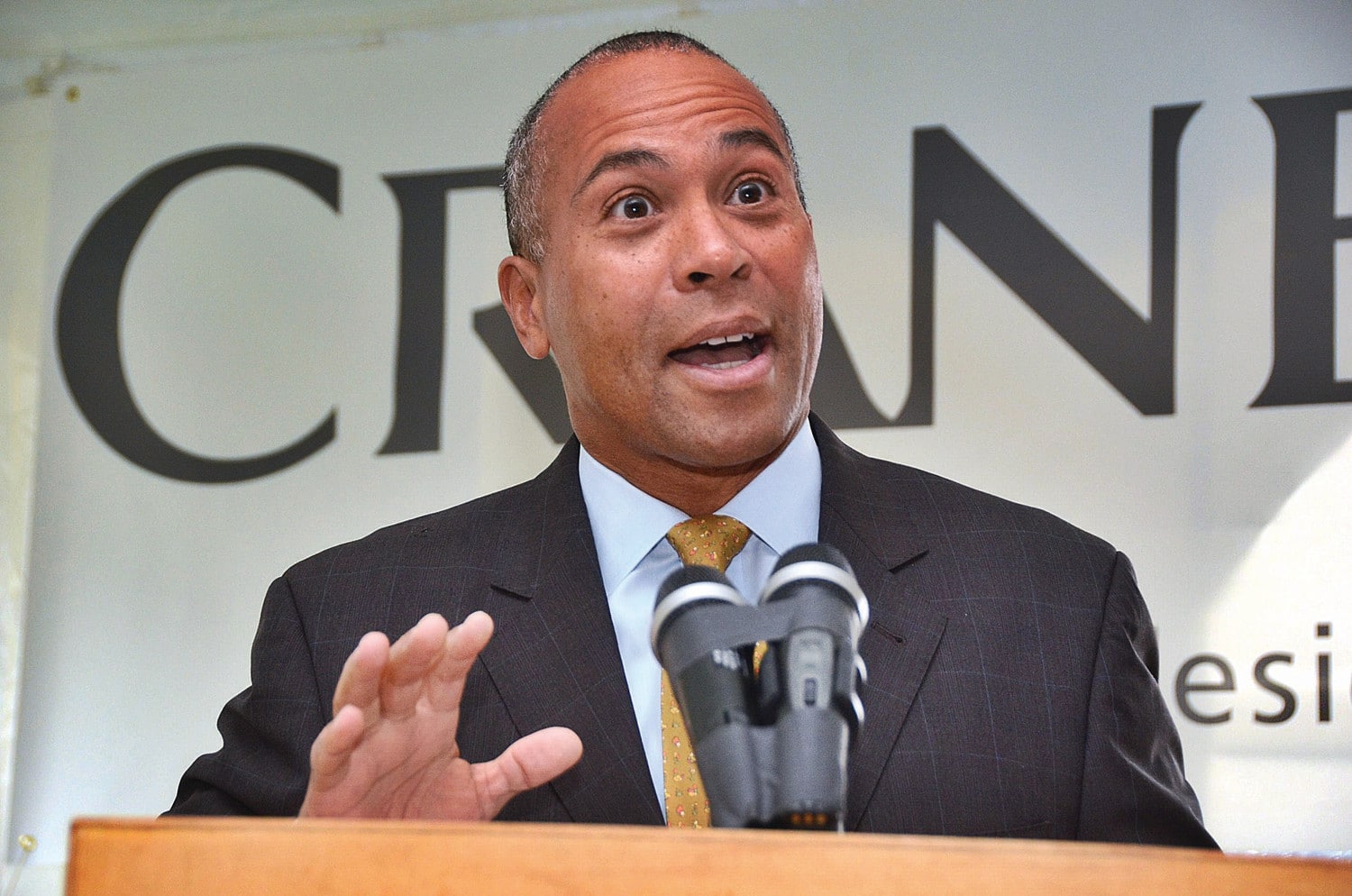

Former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick entered the presidential race last week. Patrick is touted as a centrist Democrat and is reportedly former president Barack Obama’s favorite candidate. Patrick is also the only candidate in the race responsible for disastrous coverups at both the federal and state level.

Patrick was assistant attorney general for Civil Rights in the Clinton administration. Shortly before Clinton won the 1992 election, US marshals killed 14-year-old Sammy Weaver and an FBI sniper shot Randy Weaver and killed his wife, Vicki Weaver, as she held their baby in the cabin door at Ruby Ridge.

An Idaho jury found Weaver not guilty on almost all charges and federal judge Edward Lodge slammed the Justice Department and FBI for concealing evidence and showing “a callous disregard for the rights of the defendants and the interests of justice.” A task force of 24 FBI and Justice Department officials compiled a 542-page report detailing federal misconduct and coverups and suggested criminal charges against FBI officials involved in Ruby Ridge. Patrick rejected the task force’s recommendation, ruling instead that the FBI sniper who killed Vicki Weaver had not used “excessive force” and did not intend to violate her civil rights.

When the facts came out, Patrick barely flinched

In June 1995, the secret report leaked out and made a mockery of Patrick’s “no excessive force” ruling. One FBI SWAT team member at Ruby Ridge recalled the Rules of Engagement: “If you see ’em, shoot ’em.” The report condemned that rule as practically a license to kill that flagrantly violated the US Constitution. The task force was especially appalled that the Weavers were gunned down before receiving any warning or demand to surrender, noting that the FBI’s tactics “subjected the government to charges that it was setting Weaver up for attack.” Patrick apparently shrugged off such concerns.

Top FBI officials were suspended on suspicion of committing perjury on the case the following month. Though Patrick had effectively absolved the government, the Justice Department paid $3 million to settle a wrongful death lawsuit from the Weaver family. When the Senate Judiciary Committee held hearings on Ruby Ridge later that year, five FBI officials (including the sniper who killed Vicki Weaver) involved in the case invoked their Fifth Amendment rights to avoid incriminating themselves. In 1997, the chief of the FBI’s violent crimes section was sent to prison for destroying a report on the FBI’s failures at Ruby Ridge, Idaho.

If Patrick had accepted the task force’s recommendation and permitted prosecutions, the Weaver case might not have swayed so many Americans to believe that FBI agents can kill gun owners with impunity. When FBI snipers swarmed on the scene of the Bundy Ranch five years ago, memories of Ruby Ridge spurred legions of gun-toting activists to race to the scene to protect the Bundy family. (FBI lies and misconduct in that case resulted in charges being dismissed and a federal judge condemning the bureau last year.)

In 2006, Patrick was elected governor of Massachusetts, one of the nation’s most liberal states. In July 2012, Patrick declared that “warehousing non-violent offenders is a costly policy failure” and proudly signed a bill that offered parole to a few hundred non-violent drug offenders. But despite the governor’s rhetoric, Massachusetts continued rounding up and locking away vast numbers of people caught with prohibited substances. Patrick strongly opposed decriminalizing marijuana.

The Massachusetts drug-conviction assembly line relied on state laboratories which assessed suspected narcotics. In September 2012, Massachusetts state lab chemist Annie Dookhan was arrested for falsifying tens of thousands of drug tests, “always in favor of the prosecution. Worse, when she was feeling especially helpful, she’d add bogus weight to a borderline sample,” as Rolling Stone reported. Dookhan routinely certified samples she received as illicit narcotics without ever testing them.

Governor Patrick described Dookhan as an isolated “rogue chemist” but the Boston Globe concluded that the lab debacle “crushes any hope Patrick may have had of finishing his term unburdened by scandal.” Patrick responded to the scandal by announcing plans to “create a kind of boiler room, or a war room where some folks who can work through the documents… from different agencies to make sure we get a comprehensive list” of people potentially wrongfully convicted thanks to Dookhan.

The lab scandal continued

Five months after the Dookhan scandal broke, another Massachusetts state lab chemist, Sonja Farak, was arrested for tampering with evidence as well as heroin and cocaine possession. Patrick quickly assured the media: “The most important take-home, I think, is that no individual’s due process rights were compromised” by Farak’s misconduct.

Actually, Farak had personally abused narcotics from her first day on the job in 2004 — sometimes even cooking crack cocaine on the single burner in the lab and snorting meth and cocaine in courthouse bathrooms when she was called to testify. She detailed her drug adventures in hundreds of pages of diaries, including the day she was “freaking out” and “crawling on the floor… trying to find crack, which I thought was there.”

The state attorney general’s office insisted that Farak had only started consuming narcotics at work a few months before her arrest and blocked all efforts to expose her drug binges since 2004. Massachusetts state lawyers also withheld reports “showing that the machines used for testing in Farak’s lab were issuing faulty reports” that could lead to unjustified convictions.

Though Patrick, whose second term ended in early 2015, had promised speedy justice to the wrongly convicted, state officials scorned due process and decency. Slate reported in 2015 that “district attorneys take the position that it is not their responsibility to help identify Dookhan or Farak defendants….[P]rosecutors have no special duty to notify defendants that their convictions might have been obtained with evidence that was falsified by government employees.” A ProPublica investigation noted in 2016 that “it took four years for prosecutors to even attempt to systematically notify the thousands of defendants that their convictions might have been won unfairly.” Most of the victims could not afford lawyers to challenge their convictions, resulting in innocent people spending more months and years in prison. In 2016, a judge condemned two prosecutors overseeing the challenged convictions for their “intentional, repeated, prolonged and deceptive withholding of evidence from the defendants.” More than 61,000 drug convictions were eventually overturned due to the state laboratory abuses.

Deval Patrick does not bear responsibility for either Ruby Ridge or the Massachusetts drug lab debacles, but he does bear responsibility for his responses. He compounded the first scandal, failing to stand up for the Weaver’s civil rights. And he failed to honor his pledge for speedy relief of injustice in the second scandal.

That’s not a record that qualifies Patrick for the presidency.

James Bovard, author of “Attention Deficit Democracy,” is a member of USA TODAY’s Board of Contributors. Follow him on Twitter: @JimBovard

Reprinted with author’s permission from USA Today.