For the first time since the Singapore summit, a shadow of doubt has been cast over the Korean peace process. Its source is the United States’ unyielding demand for complete North Korean nuclear disarmament before ending the Korean War and prior to allowing the sanctions exemptions needed for carrying out North-South peace initiatives.

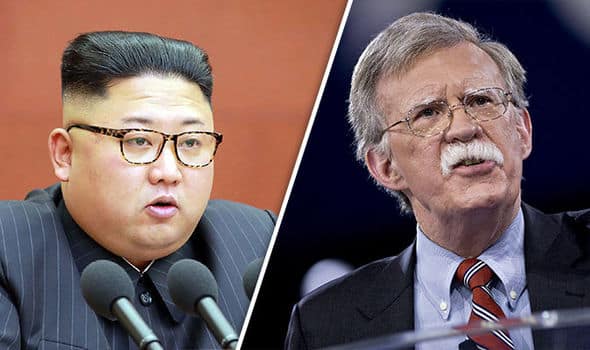

The US’ unwillingness to take a more conciliatory approach on these two issues stems from the misguided conviction among senior Trump administration officials that maximum pressure was the key to bringing Kim Jong-un to the negotiating table in the first place. These officials believe declaring the end of the war would eliminate the leverage of a military option, while sanctions exemptions would weaken the economic pressure put on North Korea, creating an environment in which their nuclear weapons arsenal is tacitly accepted.

On the contrary, the administration’s reversion to a hardline approach has exhausted the momentum provided by the Singapore summit, and their reluctance to declare an end to the war as a confidence-building measure threatens to stall the peace process completely.

More than ever, the burden rests on the shoulders of South Korean President Moon Jae-in to drive negotiations forward by pushing back against Washington’s uncompromising position. However, given the intractable nature of the current impasse, if Moon fails to convince the Trump administration to soften its stance, his government will eventually be forced to make an existential decision about South Korea’s future role in Northeast Asia.

Mike Pompeo’s Visit to Pyongyang and the US Recommitment to Maximum Pressure

After the Singapore summit, President Trump was much-maligned in the media and by his political opposition in Washington for being too soft on North Korea. On the contrary, the US government’s surprising willingness to build trust with the North by canceling provocative military drills was one of the major reasons Singapore was a success. It fostered hope on both sides of the Korean Peninsula that peace might be given a chance after all.

As a result, there was much anticipation leading up to US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s visit to Pyongyang in early July. As the first significant follow-up in negotiations since Singapore, his trip was expected to inject further momentum into the peace process, but ultimately served to do the exact opposite – a fact revealed through a North Korean Foreign Ministry missive following the meeting.

Much was made of the term “gangster-like” used in the North Korean statement when describing Pompeo’s negotiations posture, but as a whole, their dispatch was an expression of grave disappointment (“Our hopes and expectations were so naive as to be gullible”) and a warning that his hardline approach would not be conducive to successful diplomacy in the long term.

The statement described Pompeo’s position as “unilateral…denuclearization demands, calling for [complete, verifiable and irreversible nuclear disarmament],” while offering nothing of substance in terms of how to carry out the Singapore agreement (primarily, improving US-NK relations, establishing a peace regime, and working towards denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula). Their account was corroborated by a report stating Pompeo was only interested in discussing three items at the meeting: “A full declaration of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal, a timeline for dismantling the nuclear program, and an unfulfilled promise made by Kim at the summit,” the latter of which was unspecified.

It was surprising to hear North Korea react in such a negative way after Pompeo described the meeting as “successful” upon his return to Washington, but the most significant revelation from the dispatch was that the US had either changed its attitude on the importance of concessions, or had always considered the temporary cancellation of military drills to be the solitary carrot it was willing to offer the North in this process.

More specifically, it became apparent the US intends to use the potential of a peace agreement as a future reward for North Korea carrying out complete nuclear disarmament, rather than as the security bedrock needed to begin the long process of denuclearization.

US officials confirmed their new hardline position through comments made in New York on July 20th after a UN Security Council briefing on the Korean Peninsula co-hosted by a South Korean delegation. They accused North Korea of violating fuel import sanctions 89 times throughout the first five months of 2018 and appealed for Russia and China to maintain their commitment to the UN sanctions regime, adding that the violations are ongoing. “When sanctions are not enforced, the prospects for successful denuclearization are diminished,” Pompeo said (failing to note the seemingly contradictory fact that the great progress made in US-North Korean relations this year took place while these alleged violations were occurring).

Regarding concession to the North, US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley added, “What we continue to reiterate is we can’t do one thing until we see North Korea respond to their promise to denuclearize. We have to see some sort of action.”

Yeonhap News then sought clarification with a US official on July 23rdregarding the Trump administration’s position on declaring an end to the Korean War. “Peace on the Korean Peninsula is a goal shared by the world,” the official responded. “However, the international community has repeatedly made clear it will not accept a nuclear-armed [North Korea]. As we have stated before, we are committed to building a peace mechanism with the goal of replacing the Armistice agreement when North Korea has denuclearized.”(Emphasis added.)

The US has therefore reversed the order of priorities indicated in the Singapore declaration. The conciliatory approach taken by Trump at the summit has devolved into a unilateral demand for North Korean nuclear disarmament prior to any security or economic incentives from Washington – a complete non-starter for North Korea given the US’ history of regime change and deceit around the world. If the Trump administration does not back down from this position, negotiations will go nowhere and Kim Jong-un will be forced to seek alternative means to reintegrate North Korea into the global economy, a process that is already beginning.

As China Resumes Economic Cooperation with the North, US Denies South Korea Sanctions Exemptions

The US has already lost its grip on maximum economic pressure, despite its insistence that UN Security Council members hold the line on sanctions. In addition to Russia and China putting on hold the UN Security Council motion to halt all petroleum transfers to North Korea, the Chinese government has committed roughly $89 million dollars to complete a bridge connecting Liaoning Province with North Korea across the Yalu River.

The New Yalu River Bridge project was suspended in 2014 after China tightened the screws on North Korea in response to nuclear weapons testing. Its resumption is a clear violation of UN sanctions and indicates China’s intent to push forward with economic projects in the North. The governor of Liaoning Province also stated recently, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, that economic integration with North Korea is necessary to make up for harm done by the Trump administration’s tariffs.

Meanwhile, though the Moon administration has long shown public support for maintaining the entire sanctions arsenal until complete North Korean denuclearization, a report out of South Korea on July 22nd revealed that Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-hwa requested partial sanctions exemptions during the UN Security Council briefing last week. This suggests their united front with Washington on the issue is a public facade.

“Foreign Minister Kang emphasized the need for limited sanctions exemptions in specific requested areas to enable cooperation on points of discussion with North Korea,” the report stated. Kang also stressed that “the UN Security Council sanctions on North Korea are a roadblock to implementing the measures agreed upon through the Panmunjom Declaration and the various levels of North-South negotiations.” (Translated from original Korean by author.)

Kang publicly downplayed the significance of the request (which was denied by the White House anyway) upon her return to South Korea. However, Seoul’s public position has never really made sense because the maximum application of sanctions has, as Kang privately indicated, prevented the progress of such projects as cooperative reforestation and joint railway development from moving beyond the planning stages. This is due to the inability to bring necessary materials into North Korea. Meanwhile, North Korean children continue to die of completely curable diseases due to dirty water and malnutrition, issues that would be much easier to address once certain sanctions are removed.

Kang’s request also came after increasing North Korean criticism that the South is taking too long to carry out cross-border initiatives. North Korean state media most recently condemned Moon Jae-in’s government for kowtowing to Washington in negotiations and urged South Korea to change the Trump administration’s position on ending the war.

To Save the Peace Process, Moon Must Push Back on Hardline US Policies

The peace process was a Korean effort from the beginning, one that the United States merely joined in on. In spite of this, US involvement is crucial to enable the removal of sanctions holding back inter-Korean cooperation. Unfortunately, the US is demanding North Korean nuclear disarmament before peace and sanctions removal of any kind, conditions to which North Korea cannot possibly accede. To resolve this catch-22 situation, President Trump needs to reverse course back to the conciliatory approach that made the Singapore summit a success. Given that his senior officials seem ideologically opposed to doing so, the burden rests on President Moon to convince him.

Specifically, Moon must push the Trump administration to back off its insistence on complete nuclear disarmament prior to declaring the end of the Korean War. This would provide the modicum of confidence in Washington’s motives that North Korea needs to begin denuclearization. It must also insist that the end of the war be accompanied by specific sanctions exemptions, enabling the two Koreas to move forward with cooperative initiatives and thereby open up a separate, Korean-only peace process that is not directly impacted by the ups and downs of denuclearization negotiations between the US and North Korean governments.

Moon has long expressed the need for a declaration ending the Korean War and, during a recent visit to Singapore, set the end of 2018 as a target date. This best-case-scenario would require nudging the US toward a softened negotiations stance by September, when it is hoped the three parties will meet during the UN General Assembly.

To make this more palatable for Washington, the Moon administration is reportedly trying to convince the US that ending the war will require little more than a “‘political declaration’ [without] legal or institutional force.” While this alone may seem too weak for North Korea, supplementary security guarantees by China and Russia could sweeten the pot.

While in Singapore, the South Korean president noted the importance of the international community joining “efforts for North Korea’s regime security,” adding that, “the corresponding measures North Korea is demanding from the US aren’t the kind of lifting of sanctions or economic compensation it has called for in the past, but an end to hostile relations and the building of trust.” Indeed, during his visit to Moscow in June, a first for a South Korean president in two decades, Moon discussed Northeast Asian security, the peace process and economic opportunities with Russian President Vladimir Putin – perhaps an indication he is rallying support for such an approach.

For its part, North Korea continues to make overtures to Washington in spite of the US’ about-face on diplomacy. Most recently, it dismantled a site for testing ballistic missiles at some point over the last two weeks (after the failed Pompeo meeting). This was termed a “significant confidence building measure on the part of North Korea” by 38 North, a leading website for analysis on North Korea.

Kim Jong-un therefore clearly remains committed to diplomacy despite US inflexibility, at least for the time being. His enthusiasm likely won’t last forever, though; if Moon cannot convince the Trump administration to retract its demand for complete denuclearization prior to some form of peace agreement, the negotiations will inevitably pass their expiry date.

South Korea’s Role as an Agent of Influence in Northeast Asia at Stake

It is foolhardy to predict anything in the age of Trump. The US president’s willingness to go against Washington norms – sporadically for the sake of diplomacy and peace – may be Moon’s best hope in pushing through the Washington consensus for maximum pressure. However, a plethora of historical examples suggest the US imperial system is philosophically and financially invested in conflict and dominance rather than diplomacy when dealing with adversarial states. This is especially true in the case of North Korea, a country that has been on the hit list for decades.

President Moon may eventually be forced to make a decision about the fate of his country: whether or not South Korea should remain a vassal of the United States that is cut off from its northern half and the vast economic opportunities that physically reconnecting with the Asian continent represents.

There is no way to know if the current South Korean administration is bold enough to attempt a departure from the American orbit to achieve peace with North Korea, or what that process would even entail. But as China reintegrates its economy with the North, the bottom line is that South Korea may be completely left behind if Moon fails to influence the Trump administration or refuses to consider more drastic measures to continue the pursuit of Korean peace.

Reprinted with permission from Antiwar.com.