Hassan Rohani’s election as Iran’s president seven months ago caught most of the West’s self-appointed Iran “experts” by (largely self-generated) surprise. Over the course of Iran’s month-long presidential campaign, methodologically-sound polls by the University of Tehran showed that a Rohani victory was increasingly likely.

Yet Iran specialists at Washington’s leading think tanks continued erroneously insisting (as they had for months before the campaign formally commenced) that Iranians could not be polled like other populations and that there would be “a selection rather than an election,” engineered to install Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s “anointed” candidate—in most versions, former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili. On election day, as Iranian voters began casting their ballots, the Washington Post proclaimed that Rohani “will not be allowed to win”—a statement reflecting virtual consensus among American pundits.

Of course, this consensus was wrong—as have been most of the consensus judgments on Iran’s politics advanced by Western analysts since the country’s 1979 revolution. After Rohani’s victory, instead of admitting error, America’s foreign policy elite manufactured two explanations for it. One was that popular disaffection against the Islamic Republic—supposedly reflected in Iranians’ determination to elect the most change-minded candidate available to them—had exceeded even the capacity of Khamenei and his minions to suppress. This narrative, however, rests on agenda-driven and false assumptions about who Rohani is and how he won.

At sixty-five, Rohani is not out to fundamentally change the Islamic Republic he has worked nearly his entire adult life to build. The only cleric on the 2013 presidential ballot, Rohani belongs to Iran’s main conservative clerical association, not its reformist antipode. While he has become the standard bearer for the Islamic Republic’s “modern” (or “pragmatic”) right, with considerable support from the business community, his ties to Khamenei are also strong. After Rohani stepped down as secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council in 2005, Khamenei made Rohani his personal representative on the Council.

Backing Rohani was thus an unlikely way for Iranian voters to demand radical change, especially when an eminently plausible reformist was on the ballot—Mohammad Reza Aref, a Stanford Ph.D. in electrical engineering who served as one of reformist President Mohammad Khatami’s vice presidents. (Methodologically-sound polls showed that Aref’s support never exceeded single digits; he ultimately withdrew three days before Iranians voted.) The outcome, moreover, hardly constituted a landslide—not for Rohani and certainly not for reformism: Rohani won by just 261,251 votes over the 50-percent threshold for victory, and the parliament elected just one year before is dominated by conservatives.

The other explanation for Rohani’s success embraced by American elites cites it as proof that U.S.-instigated sanctions are finally “working”—that economic distress caused by sanctions drove Iranians to elect someone inclined to cut concessionary deals with the West. But the same polls that accurately predicted Rohani’s narrow win also show that sanctions had little to do with it. Iranians continue to blame the West, not their own government, for sanctions. And they do not want their leaders to compromise on what they see as their country’s sovereignty and national rights—rights manifest today in Iran’s pursuit of a civil nuclear program.

The Iranian Challenge

Iran’s presidential election and the smooth transfer of office to Rohani from term-limited incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad stand out in today’s Middle East. Compared to Afghanistan, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Palestine, Syria, and Tunisia, the Islamic Republic is actually living up to former U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s description of Iran as “an island of stability” in an increasingly unsettled region. And compared to some Gulf Arab monarchies, where perpetuation of (at least superficial) stability is purchased by ever increasing domestic expenditures, the Islamic Republic legitimates itself by delivering on the fundamental promise of the revolution that deposed the last shah thirty-five years ago: to replace Western-imposed monarchical rule with an indigenously generated political model integrating participatory politics and elections with principles and institutions of Islamic governance.

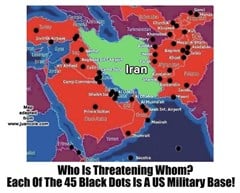

These strengths have enabled the Islamic Republic to withstand sustained regional and Western pressure, and to pursue a foreign policy strategy likely to reap big payoffs in 2014. This strategy aims to replace American hegemony, regionally and globally, with a more multi-polar distribution of power and influence. It seeks to achieve this by using international law and institutions, and by leveraging the Islamic Republic’s model of participatory Islamist governance, domestic development, and foreign policy independence to accumulate real “soft power”—not just with a majority of Iranians living inside their country, but (according to polls) with hundreds of millions of people across the Muslim world and beyond, from Brazil to China and South Africa. Such soft power was on display, for example, in the last year of Ahmadinejad’s presidency, when, during a trip to China, he won a standing ovation from a large audience at Peking University, where a representative sample of next-generation Chinese elites showed themselves deeply receptive to his call for a more equitable and representative international order.

In the current regional and international context, the West is increasingly challenged to come to terms with the Islamic Republic as an enduring entity representing legitimate national interests. In Tehran, the United States and its European allies could have a real partner in countering al-Qa’ida-style terrorism and extremism, in consolidating stable and representative political orders in Syria and other Middle Eastern trouble spots, and in resolving the nuclear issue in a way that sets the stage for moving toward an actual WMD-free zone in the region. But partnering with Tehran would require Washington and its friends in London and Paris to accept the Islamic Republic as the legitimate government of a fully sovereign state with legitimate interests—something that Western powers have refused to accord to any Iranian government for two centuries.

President Obama’s highly public failure to muster political support for military strikes against the Assad government following the use of chemical weapons in Syria on August 21, 2013 has effectively undercut the credibility of U.S. threats to use force against Iran. On November 24, 2013, this compelled an American administration, for the first time since the January 1981 Algiers Accords that ended the embassy hostage crisis, to reach a major international agreement with Tehran—the interim nuclear deal between Iran and the P5+1—largely on Iranian terms. (For example, the interim nuclear deal effectively negates Western demands—long rejected by Tehran but now enshrined in seven UN Security Council resolutions—that Iran suspend all activities related to uranium enrichment).

But recent Western recognition of reality is still partial and highly tentative. The United States and its British and French allies continue to deny that Iran has a right to enrich uranium under international safeguards. They also demand that, as part of a final deal, Tehran must shut down its protected enrichment site at Fordo, terminate its work on a new research reactor at Arak, and allow Western powers to micromanage the future development of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure. Such positions are at odds with the language of the interim nuclear deal and of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). They are also as hubristically delusional as the British government’s use of the Royal Navy to seize tankers carrying Iranian oil on the high seas after a democratically-elected Iranian government nationalised the British oil concession in Iran in 1951—and as London’s continued threat to do so even after the World Court ruled against Britain in the matter.

If Western powers can realign their positions with reality on the nuclear issue and on various regional challenges in the Middle East, Iran can certainly work with that. But Iranian strategy takes seriously the real prospect that Western powers may not be capable of negotiating a nuclear settlement grounded in the NPT and respectful of the Islamic Republic’s legal rights—just as Britain and the United States were unwilling to respect Iran’s sovereignty over its own natural resources in the early 1950s. Under such circumstances, more U.S.-instigated secondary sanctions that illegally threaten third countries doing business with Iran will not compel Tehran to surrender its civil nuclear program. Rather, Iran’s approach—including a willingness to conclude what the rest of the world other than America, Britain, France, and Israel would consider a reasonable nuclear deal—seeks to make it easier for countries to rebuild and expand economic ties to the Islamic Republic even if Washington does not lift its own unilaterally-imposed sanctions.

Likewise, Iranian strategy takes seriously the real prospect that Washington cannot disenthrall itself from Obama’s foolish declaration in August 2011 that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad must go—and therefore that America cannot contribute constructively to the quest for a political settlement to the Syrian conflict. If the United States, Britain, and France continue down their current counter-productive path in Syria, Tehran can play off their accumulating policy failures and the deepening illegitimacy of America’s regional posture to advance the Islamic Republic’s strategic position.

How Will the West Respond?

Coming to terms with the Islamic Republic will require the United States to abandon its already eroding pretensions to hegemony in the Middle East. But, if Washington does not come to terms with the Islamic Republic, it will ultimately be forced to surrender those pretensions, as it was publicly and humiliatingly forced to do in 1979. Moreover, continuing hostility toward the Islamic Republic exacerbates America’s inability to deal with popular demands for participatory Islamist governance elsewhere in the Middle East. Less than a month after Rohani’s election, it was widely perceived that the United States tacitly supported a military coup that deposed Egypt’s first democratically elected (and Islamist) government. The coup in Egypt hardly obviates the fact that, when given the chance, majorities in Middle Eastern Muslim societies reject Western intervention and choose to construct participatory Islamist orders. Refusing to accept this reality will only accelerate the erosion of U.S. influence in the region.

The United States is not the first imperial power in decline whose foreign policy debate has become increasingly detached from reality—and history suggests that the consequences of such delusion are usually severe. The time for American elites to wake up to Middle Eastern realities before the United States and its Western allies face severe consequences for their strategic position in this vital part of the world is running out.

Reprinted from Going to Tehran blog.