“The lamps are going out all over Europe,” Sir Edward Grey famously said on the eve of World War I. “We shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.”

It was 100 years ago this week that Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, setting in motion the unspeakable calamity that contemporaries dubbed the Great War. Well in excess of 10 million people perished, and by some estimates, many more.

Numbers, even staggering ones like this, can scarcely convey the depth and breadth of the destruction. The war was an ongoing slaughter of devastating proportions. Tens of thousands perished in campaigns that moved the front just a matter of yards. It was World War I that gave us the term “basket case,” by which was meant a quadruple amputee. Other now-familiar tools of warfare came into common use: the machine gun, the tank, even poison gas. Rarely has the State’s machinery of senseless destruction been on more macabre display.

The scholarly pendulum has swung back in the direction of German atrocities having indeed been committed in Belgium, though perhaps not quite as gruesome as the tales of babies being passed from bayonet to bayonet that were disseminated to Americans early in the war. In turn, a vastly larger number of Germans, with estimates as high as 750,000, died as a result of the British hunger blockade that violated longstanding norms of international conduct, even during wartime.

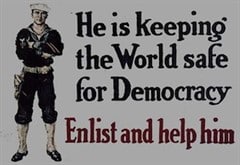

The machinery of State propaganda reached heights never before seen. Whole peoples were systematically demonized in the service of the warmakers. Sound money was abandoned, to return only briefly and in a hobbled form during the interwar period.

To be sure, some socialists opposed the war, since it pitted the working classes of the world against each other. Others, intoxicated by the spirit of nationalism, abandoned socialism (at least in its internationalist aspects) and plunged into the war with gusto. Among these: Benito Mussolini.

And yet there is scarcely an atrocity that States cause that another State, in the name of peace, cannot make indescribably worse.

The intervention by Woodrow Wilson, against the wishes of most Americans – were that not so, neither the draft nor the ceaseless propaganda would have been necessary – was one of the most catastrophic decisions ever made, by anyone. It set in motion a sequence of events whose consequences would reverberate throughout the 20th century.

One can make a case, not merely plausible but indeed quite compelling, that in the absence of Wilson’s intervention, the entire litany of 20th-century horrors could have been avoided. Without a punitive peace, which only Wilson’s intervention made possible, the Nazis would have had no natural constituency, and no path to power. The Bolshevik Revolution, which succeeded only because of the unpopularity of the war, might not have occurred if the promise of coming American support had not kept that war going.

Even George Kennan, a pillar of the establishment, admitted in retrospect: “Today if one were offered the chance of having back again the Germany of 1913 – a Germany run by conservative but relatively moderate people, no Nazis and no Communists – a vigorous Germany, full of energy and confidence, able to play a part again in the balancing-off of Russian power in Europe, in many ways it would not sound so bad.”

Meanwhile, the Turkish collapse, writes Philip Jenkins, led some Muslims to seek a different basis on which to unify, and that in turn has encouraged the most illiberal forms of Islam.

Oh, but everyone is against war, right?

Yes, just about everyone makes the perfunctory nod to the tragedy of war, that war is a last resort only, and that everyone sincerely regrets having to go to war.

But war has been at the heart of much modern ideology. For years, Theodore Roosevelt had exulted at the prospect of war. Peace was for the weak and flabby. The strains of war were a school of discipline and manliness, without which nations degenerate. Fascists, in turn, urged their countries to adopt for domestic use the patterns of military life: regimentation, limitations on dissent, the common pursuit of a single goal, proper reverence for The Leader, the subordination of all other allegiances in favor of loyalty to the State, and the priority of the “public interest” over mere private interests.

If the fascist right has been rightly associated with militarism, that isn’t because the revolutionary left has been any less dedicated to organized violence. Robert Nisbet wrote, “Napoleon was the perfect exemplar of revolution as well as of war, not merely in France but throughout almost all of Europe, and even beyond. Marx and Engels were both keen students of war, profoundly appreciative of its properties with respect to large-scale institutional change. From Trotsky and his Red Army down to Mao and Chou En-lai in China today, the uniform of the soldier has been the uniform of the revolutionist.”

For their part, those people we associate with progressivism in the United States, with only a handful of exceptions, overwhelmingly favored intervening in the war. They favored it not only out of the bipartisan sense of American righteousness that goes back as far as one cares to look, but also precisely because they knew war meant bigger and more intrusive government. They knew it would make people accustomed to the idea that they can be called upon to carry out the State’s program, whatever it may be.

Murray N. Rothbard drew up the indictment of the Progressives on this count. He added that the standard view of historians that World War I amounted to the end of Progressivism was exactly backwards: World War I, with its economic planning, the impetus it gave to government growth, and its disparagement of private property and the mundane concerns of bourgeois life, represented the culmination of everything the Progressive movement represented.

By contrast, war is the very negation of the libertarian creed. It disrupts the international division of labor. It treats human beings as disposable commodities in the service of State ambition. It undermines commerce, sound money, and private property. It results in an increase of State power. It demands the substitution of the great national effort in place of the private interests of free individuals. It urges us to sympathize not with our fellow men around the world, but with the handful of people who happen to administer the State apparatus that rules over us. We are encouraged to wave the flags and sing the songs of our expropriators, as the poor souls on the other side do the same.

In the hands of commerce and the market, the fruits of capitalist civilization improve living standards and lift people out of destitution. But the political class cannot be trusted with these good things. The very success of the market economy has meant more resources to be siphoned off by the warmakers. As Ludwig von Mises wrote in Nation, State, and Economy (1919):

War has become more fearful and destructive than ever before because it is now waged with all the means of the highly developed technique that the free economy has created. Bourgeois civilization has built railroads and electric power plants, has invented explosives and airplanes, in order to create wealth. Imperialism has placed the tools of peace in the service of destruction. With modern means it would be easy to wipe out humanity at one blow. In horrible madness Caligula wished that the entire Roman people had one head so that he could strike it off. The civilization of the twentieth century has made it possible for the raving madness of the modern imperialists to realize similar bloody dreams. By pressing a button one can expose thousands to destruction. It was the fate of civilization that it was unable to keep the external means that it had created out of the hands of those who had remained estranged from its spirit. Modern tyrants have things much easier than their predecessors….

Nothing in the world is easier than opposing a war that ended long ago. It takes no real courage to be against the Vietnam War in 2014. What takes courage is opposing a war while it is being fought – when the propaganda and intimidation of the public are at their height – or even before it breaks out in the first place. With the memory of the moral and material catastrophe of World War I before us 100 years later, let us pledge never again to be fooled and exploited by the State and its violent pastimes.

Reprinted with permission from LewRockwell.com.