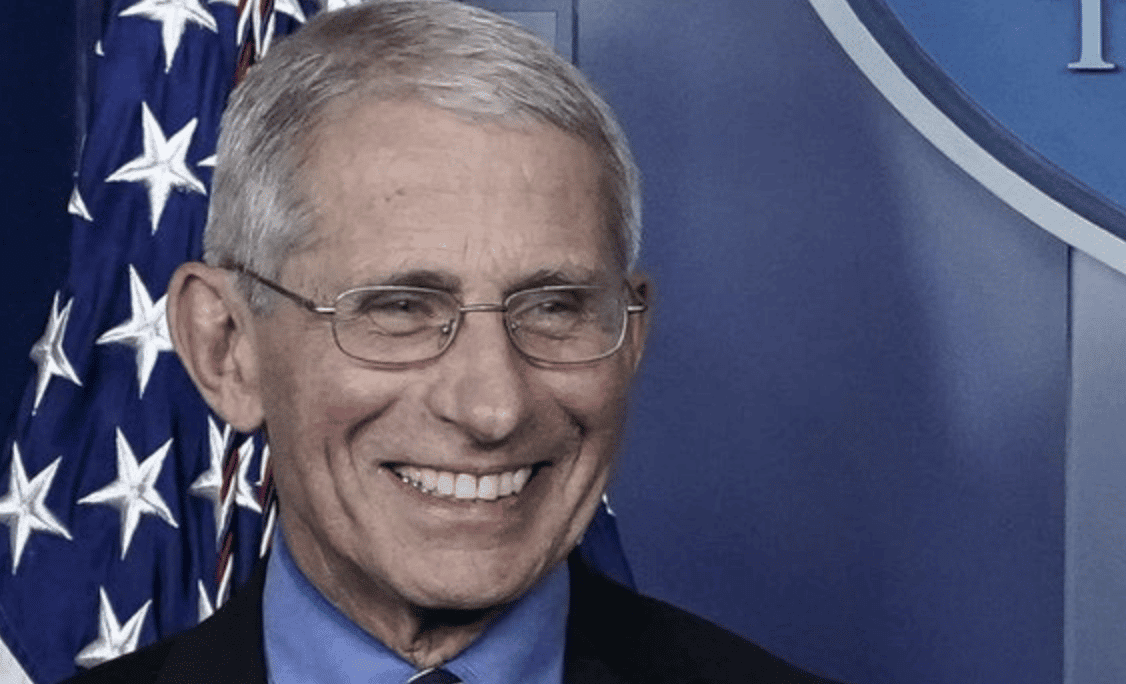

In an explosive Senate hearing on March 18, Dr. Anthony Fauci clashed with Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul over a subject that has characterized much of the White House health adviser’s recent commentary on Covid-19: the specter of reinfection, caused by one of the emerging variants of the virus.

Several recent studies suggest that both natural and vaccine-induced immunity to Covid-19 is robust at least for the medium term, and even those hinting at possible reinfections suggest it is a rare phenomenon mainly afflicting people with severely weakened immune systems.

Fauci nonetheless maintains that reinfections, particularly from the South African variant of the virus, are not only commonplace but justify maintaining a suite of restrictive nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPI) such as lockdowns, mask mandates, and social distancing regulations – perhaps even for another year.

Paul pressed Fauci to cite the scientific literature supporting this claim, to no avail. Instead, Fauci deflected the question by repeating platitudes about masks and exaggerating a recent study about reinfections. According to Fauci, previously recovered people who “were exposed to the variant in South Africa” reacted “as if they had never been infected before. They had no protection.”

A Danish study that Fauci later referenced to justify this assertion made no such claim about reinfection being widespread. Quite the contrary, its authors concluded “that protection against repeat SARS-CoV-2 infection is robust and detectable in the majority of individuals, protecting 80% or more of the naturally infected population who are younger than 65 years against reinfections.”

They did further observe “that individuals aged 65 years and older had less than 50% protection against repeat SARS-CoV-2 infection” and recommended targeted vaccinations for this group to bolster immunity. But even this finding came with several acknowledged limitations, as the study was not designed to test for repeat infection among the vast number of mild or asymptomatic cases of the disease, or to directly verify whether suspected reinfection cases were the result of misclassified lingering infections.

The study did not, however, support Fauci’s contention that reinfections are becoming commonplace.

Last week’s hearing is not the first time in recent memory that Fauci has exaggerated the evidence around reinfection, specifically invoking the South African variant. In early February, a pair of studies produced evidence that reinfections from this strain were possible, although at this point they appear to be rare. The first confirmed one single case of reinfection from the South African variant after extensive testing to rule out a misclassified lingering infection.

The second, conducted as part of the Novavax vaccine trial, indirectly inferred that a tiny number of its participants may have become reinfected with the South African variant, “suggest[ing] that prior infection with COVID-19 may not completely protect against subsequent infection by the South Africa escape variant.”

In no sense did either study claim that reinfections are commonplace or widespread. If anything, they were measured scientific calls for further investigation of each possibility. Yet here is how Fauci described them in a mid-February interview with CNN: “[t]he experience of our colleagues in South Africa indicates that even if you’ve been infected with the original virus, that there is a very high rate of re-infection to the point where previous infection does not seem to protect you against re-infection, at least with the South African variant.”

This sort of overstatement is a familiar theme for the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) lead infectious disease bureaucrat, dating all the way back to his mishandling of the AIDS crisis in the early 1980s. Fauci has a bad habit of seizing onto a small kernel of scientific data, drawing sweeping inferences upon it through unfounded speculation, and then presenting his own exaggerated spin to the public as if it is a matter of scientific fact.

Fauci’s Mutating Scientific Commentary

All the more curious, Fauci’s recent exaggerations about Covid-19 reinfection place him in direct conflict with another “expert” assessment of the very same question: his own, at various points over the course of the pandemic in the last year.

On March 28, 2020 – just shy of a year before his recent tangle with Senator Paul – Fauci aggressively contested the likelihood of reinfection in an interview with the Daily Show’s Trevor Noah. “It’s never 100%,” he explained, “but I’d be willing to bet anything that people who recover are really protected against re-infection.”

The NIH administrator’s many credulous enthusiasts in the news media will likely respond to such contradictory assertions by claiming that Fauci is simply updating his assessment in light of new evidence. Yet his track record over the past year suggests a very different story. Far from incorporating the latest scientific findings, Fauci appears to selectively invoke or downplay the specter of reinfection based on whether or not it serves his political objectives of the moment.

Fauci’s claims about reinfection do not follow a consistent trajectory of emerging evidence about whether or how frequently it happens. Instead they vacillate between depicting the possibility as either an overblown fear, concerning only a few rare cases, or an imminent cause for alarm that could spread to the entire population.

During the first several months of lockdowns in the United States, Fauci repeatedly asserted that immunity from the virus would preclude reinfection among those who had contracted the disease and recovered. “It’s a reasonable assumption that this virus is not changing very much,” he explained on an early April 2020 webcast for the Journal of the American Medical Association. “If we get infected now and it comes back next February or March we think this person is going to be protected.”

Fauci repeated a similar claim in a July 2020 interview with NIH director Francis Collins, who specifically asked him about the possibility of reinfection. “I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a rare case of an individual who went into remission and relapse,” he explained, “But Francis, I could say with confidence that it is very unlikely.”

These early statements aligned with Fauci’s political messaging in the first few months of the pandemic. He was operating under the assumption that lockdowns would successfully contain the virus, even praising Europe at the time for “successfully” pulling off this strategy (the fall second wave would belie this claim, as well as the notion that lockdowns even minimally guard against the course of the virus). If the United States would only accept similar measures through the summer and perhaps fall, the pandemic could be tamed through NPIs. Meanwhile, reinfections remained a non-issue in Fauci’s eyes.

When medical researchers documented one of the first confirmed cases of reinfection last August, Fauci saw no cause for alarm. During a virtual address to the staff of the Walter Reed Medical Center on August 26, he dismissed the prospect as “purely rare and anecdotal.” Fauci continued: “In every anecdotal case I’ve seen, there could have been another explanation for that. So, I can say that although we have to leave open the possibility, it is likely so, so rare that right now with what we know, it’s not an issue.”

Keep in mind that this description could just as easily apply to the recent studies of the South African strain, which have only confirmed or suggested a tiny number of reinfections. Fauci simply interpreted these earlier studies with greater caution and restraint against exaggerating their implications.

Not long after his August 2020 remarks, Fauci’s messaging on reinfections shifted to an opposite tack. With the looming prospect of another round of lockdowns in the fall, a group of scientists convened for a weekend meeting at AIER. On October 4th they issued the Great Barrington Declaration (GBD), challenging the efficacy of Fauci’s lockdown-centered strategy and calling attention to the widespread collateral harms it had inflicted on society. Instead, the GBD argued, we should adopt a strategy of “focused protection” for the most vulnerable until we built up herd immunity in the general population.

Herd immunity is a biological fact rather than a policy strategy. It comes about through the combination of naturally acquired immunity from recovered persons, and vaccine-induced immunity among the still-vulnerable. With anticipated testing and approval of the first vaccines in the late fall or winter, focused protection offered a viable pathway to reopening and thereby alleviating the widespread social and economic destruction caused by the lockdowns over the last year.

Suddenly Fauci began pivoting his messaging on reinfections. Shortly after the GBD came out, White House coronavirus adviser Dr. Scott Atlas endorsed “focused protection” as an alternative to a perpetual cycle of lockdowns. Fauci himself previously conceded the reality of herd immunity effects in the spring and summer when he pointed out that reinfections were anecdotal, rare, and unlikely. But now he saw his political authority being challenged by the GBD authors and by Atlas’s parallel recommendations.

On October 16, 2020 Fauci accordingly went on CNN with a new message of alarm about reinfections: “We’re starting to see a number of cases that are being reported of people who get re-infected, well-documented cases of people who were infected after a relatively brief period of time. So you really have to be careful that you’re not completely immune.”

Fauci’s statement implied that he had access to a growing body of new evidence on reinfection. In reality, he had a textbook example of the type of case he previously characterized as “rare and anecdotal” in August when he was trying to allay fears of the same phenomenon. A few days prior to the October CNN interview, a team of researchers in the Netherlands reported a single confirmed case in which an 89-year-old patient undergoing treatment for advanced cancer had contracted the disease, recovered, and then passed away after becoming reinfected with another strain. To Fauci however, the possibility of reinfection – once dismissed as an uncommon occurrence – became a political tool to ward off the GBD’s challenge to the lockdowns.

For the next several weeks, Fauci raised the reinfection specter whenever the subject of herd immunity came up. “We have seen specific instances of re-infection, people who got infected, recovered, and got infected with another SARS Covid-2,” he claimed in a C-Span interview that aired on November 12th. This statement came in response to questions about herd immunity from the NIH’s Francis Collins – the same person who asked a similar question in July. Recall Fauci’s answer then: “I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a rare case of an individual who went into remission and relapsed…But Francis, I could say with confidence that [re-infection] is very unlikely.”

On November 18th Pfizer announced the successful completion of its vaccine trial and intention to seek emergency authorization from the FDA within a matter of days. Fauci, who had been deprecating the herd immunity concept and hinting at reinfection only a week prior, pivoted his messaging yet again.

In a sense, he had no other option. The central premise of vaccination is to expedite reaching herd immunity in the population. As the GBD authors noted, natural immunity among the recovered and vaccination among the still-vulnerable work in concert with each other, bringing society above the necessary threshold for population-wide herd immunity. Initially, Fauci concurred, stating in an interview on November 22nd that “if you get an overwhelming majority of the people vaccinated with a highly efficacious vaccine, we can reasonably quickly get to the herd immunity that would be a blanket of protection for the country.

Within a matter of days, Fauci’s rhetoric shifted even further away from reinfection and toward touting the medium-term efficacy of immunity after vaccination. On November 27th he told McClatchy News: “From what we know of the duration thus far of immunity, I would be surprised if it turns out to be a 20-year duration, but I would also be surprised if it was less than a year. I think it would probably be more than a year.” A few days later, Fauci told Fox News that the country would reach herd immunity once about 70% received the vaccine.

Then the goalposts shifted

Faced with mounting political pressures to relax lockdowns and other NPI measures in the wake of the vaccine, Fauci began casting about for new rationales to extend their duration. In a now-notorious interview with the New York Times’s Donald McNeil on December 24th, Fauci bumped his herd immunity threshold upward toward 90%. The lower targets from the previous month, he now insisted, were part of an elaborate noble lie to coax the public into greater compliance with his own directives: “When polls said only about half of all Americans would take a vaccine, I was saying herd immunity would take 70 to 75 percent. Then, when newer surveys said 60 percent or more would take it, I thought, ‘I can nudge this up a bit,’ so I went to 80, 85.”

Throughout this period, the public discussion around Covid-19 refocused on the emergence of new variants of the disease caused by ongoing mutations of the original virus. Fauci’s messaging shifted as well, focusing again on the matter of reinfections with a clear message of downplaying the risk. That’s the argument he conveyed to California Governor Gavin Newsom in a brief webcast on December 31, 2020. The new UK variant, he insisted at the time, “doesn’t seem to evade the protection that’s afforded by the antibodies that are produced by vaccines…people who have been infected don’t seem to get reinfected by this.”

With each new strain however, Fauci’s message continued to pivot. By mid-February, as noted above, he was again raising the specter of reinfection from the new South African variant as a pretext for keeping mask mandates and social distancing requirements in place, even after vaccination. Fauci also pivoted away from setting target thresholds for herd immunity as vaccination numbers rapidly rose in the early spring. On March 15, 2021 he told a White House press conference that “We should not get so fixated on this elusive number of herd immunity” and should instead simply focus on vaccinating as many people as we can.

Fauci’s exchange with Rand Paul over the possibility of reinfections would take place later that same week, where he again engaged in unfounded speculation based on emerging evidence from the South African variant. While the aforementioned studies of this variant documented or inferred the possibility of reinfection, neither supported the claim that this was common or widespread.

Except Fauci’s depiction of them offered no such nuance. Instead, he offered Paul a sweeping generalization at the March 18, 2021 hearing. People with prior Covid-19 infection “had no protection” from the South African variant, according to Fauci. He doubled down on the exaggerated speculation the next day, telling CNN “I’m afraid, if people hear what Rand Paul says, and believe it, and you have an elderly person who has been infected, and they decide, ‘Well, Rand Paul says let’s not wear a mask,’ they won’t. They could get reinfected again and get into trouble.”

In just under a year’s time, Fauci’s messaging on reinfection and herd immunity has now mutated across dozens of variants of its own, each conveniently aligning with his political messaging of the moment. Although reinfection from new strains continues to be an avenue of research and investigation, the evidence we currently have suggests it remains uncommon. That hasn’t stopped America’s “leading infectious disease authority” from indulging in wildly irresponsible speculation from a national stage though, invariably appealing to alarmism as a pretext for continuing the same failed lockdown policies he has been peddling for over a year now.

Reprinted with permission from American Institute for Economic Research.