As the world waits to see if Iran and the P5+1 reach a final nuclear agreement by November 24, we remain relatively pessimistic about the prospects for such an outcome. Above all, we are pessimistic because closing a comprehensive nuclear accord will almost certainly require the United States to drop its (legally unfounded, arrogantly hegemonic, and strategically senseless) demand that the Islamic Republic dismantle a significant portion of its currently operating centrifuges as a sine qua non for a deal.

While we would love to be proved wrong on the point, it seems unlikely that the Obama administration will drop said demand in order to close a final agreement.

Alternatively, a final deal would become at least theoretically possible if Iran agreed to dismantle an appreciable portion of its currently operating centrifuges, as Washington and its British and French partners demand. However, we see no sign that Tehran is inclined to do this. Just last week, Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi reiterated that, in any agreement, “all nuclear capabilities of Iran will be preserved and no facility will be shut down or even suspended and no device or equipment will be dismantled.”

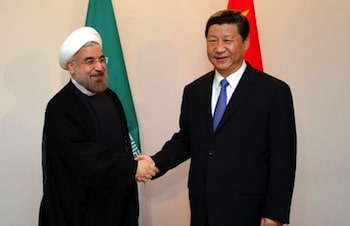

Still, almost regardless of the state of U.S./P5+1 nuclear diplomacy with Iran a month from now, the Islamic Republic’s relations with a wide range of important states are likely to enter a new phase. Among these states, China figures especially prominently.

To explore the historical factors and contemporary dynamics shaping the prospective trajectory of Sino-Iranian relations, we have written a working paper, American Hegemony (and Hubris), the Iranian Nuclear Issue, and the Future of Sino-Iranian Relations. It has been posted online, see here to download, as part of the Penn State Law Legal Studies Research Paper Series. It will soon be published as a chapter in a forthcoming volume on The Emerging Middle East-East Asia Nexus.

As our paper notes, the People’s Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Iran have, over the last three decades, “forged multi-dimenstional cooperative relations, emphasizing energy, trade and investment, and regional security.” There are compelling reasons for this. Among other things, both political orders were born of revolutions dedicated to restoring their countries’ independence and sovereignty after extended periods of dominance by foreign—above all, Western—powers. Today, both are pursuing what we describe as “counter-hegemonic” foreign policies, especially vis-à-vis the United States.

But, while U.S. primacy incentivizes closer Sino-Iranian ties, it has also kept those ties from advancing as far as they might have otherwise, particularly on the Chinese side. Over the years, Beijing has tried to balance its interests in developing ties to Tehran with its interest in maintaining at least relatively positive relations with Washington. Our paper examines a series of trends that are reducing China’s willingness to continue accommodating U.S. pressure over relations with Iran.

We assess that, as these trends play out, “Chinese policymakers will continue seeking an appropriate balance between China’s relations with the Islamic Republic and its interest in maintaining positive ties to the United States. Nevertheless, [this] balance will continue shifting, slowly but surely, toward more focused pursuit of China’s economic, energy, and strategic interests in Iran.”

We also argue that, unless the United States fundamentally revises its own posture toward the Islamic Republic, “a deepening of Sino-Iranian relations will almost certainly accelerate trends in the international economic order—e.g., backlash against Washington’s increasingly promiscuous use of financial sanctions as a foreign policy tool and the slow erosion of dollar hegemony—that are weakening America’s global position.”

We look forward to a lively discussion.

Reprinted with authors’ permission.