If there was a prize for the world’s most ineffective institution, the International Criminal Court would win hands down.

Consider this: The court has been in operation for fifteen years, has spent over a billion Euros, and has convicted just four war criminals. Yes, that’s correct. In a decade and a half, an institution proclaiming itself the world’s first permanent war crimes court has jailed just four war criminals.

In any other justice system that kind of abysmal conviction rate would get its chiefs sacked. But not the ICC. They continue to have a comfortable luxurious life in The Hague, ruling on the handful of cases that come their way, while the world’s wars rage fiercer than ever.

One reason the ICC is such a disaster is the paradox at the heart of its existence.

The ICC is not part of the United Nations. Instead, it has authority over the 124 states that have joined it. But most states likely to commit war crimes don’t join the ICC. The result? A court full of states that don’t commit war crimes.

The big three powers, the United States, China, and Russia have have all refused to join, concerned about accountability. The US State Department puts it best, saying there are “insufficient checks and balances on the authority of the ICC prosecutor and judges,” and the court has “insufficient protection against politicized prosecutions or other abuses.”

A close look at the ICC shows these concerns are well founded.

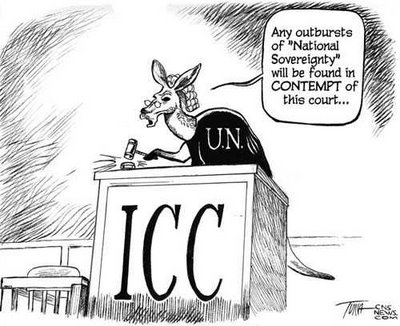

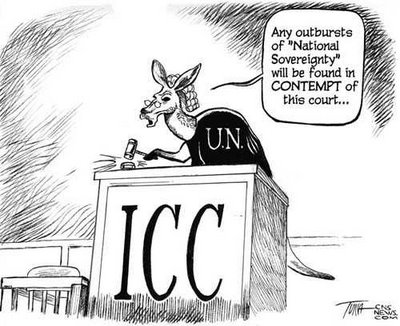

Other court systems in other parts of the world are controlled by governments. The ICC is controlled by majority votes among its member states, but those states have no power over legal decisions themselves. In effect, the ICC runs itself.

Nor does the ICC have juries. In the Hague, the judges are the jury also.

Most seriously, the ICC has no legal oversight body to keep it honest.

Most states around the world have fully independent appeals processes, like the US Supreme Court, which is separated from the courts it keeps in line.

Not the ICC. It does have an appeals court, but its appeal judges are part of the ICC. They socialise, inevitably, with the rest of the ICC in the Hague.

Even when the UN does get involved, the results at the ICC are dismal. The UN Security Council can order the ICC to investigate war crimes in a State that is not an ICC member. It did just that with Sudan and Libya. But so far, nobody from either country has been jailed by the Hague.

The latest ICC Libya indictment has been been issued against an army special forces commander charged with executions in Benghazi. But many Libyans wonder why the most terrible crimes seen in Libya in recent years, such as televised mass executions by Islamic State, go unpunished. Why has the ICC has decided not to indict ISIS, the most horrific force on the planet?

Another controversy is the trial of Gaddafi’s former intelligence chief Abdullah al Senussi, who Hague judges decided could be tried in Libya despite the country being in the grip of war and chaos. A mad cap trial, guarded by militias, ended with a death sentence in a process slammed by human rights groups.

Meanwhile, African leaders are furious that their continent is the only one being investigated. Until January last year all nine ICC cases were in Africa, and the only change since then is the addition of, of all places, Georgia!

Several African states, including South Africa, have mooted or actually quit the ICC altogether.

Maybe some in the ICC assume that African states require the Europeans in Holland to keep Africans in line and adhering to human rights practices not through their own judicial institution but by a internationally politically manipulated ICC kangaroo Court.

Finally, when cases finally get underway, they last for what seems like an eternity. Former Ivory Coast president Laurent Gbagbo was arrested for alleged rights violations in 2011 but his Hague trial didn’t get going until January of last year and is still continuing. If he’s found innocent this year, he will have spent more than seven years locked up in a Hague prison for nothing. Justice? Not exactly. This July, Presiding Judge Piotr Hofmański rejected a decision by the trial judges denying the 72-year-old Gbagbo interim release.

Yet, unbelievably, ICC spending keeps growing, jumping from 80 million Euros a year in 2007 to 141 Euros last year.

A sign of the ICC’s impotence is the recent ruling in the Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir case. Even though the ICC wanted to send a clear message to all its members, and to South Africa, with their ruling, Bashir travelled in and out with impunity. The South African government was not going to observe the ICC’s ruling. It’s that simple.

The ICC must either be totally reformed or, preferably, disbanded. It is the antithesis of truth and justice and inevitably a hindrance to peace and reconciliation in countries they purport to investigate.