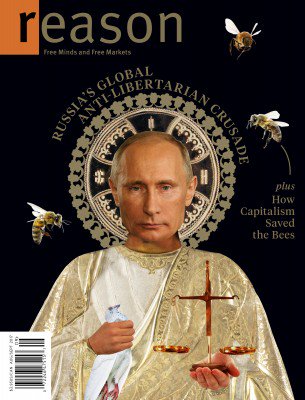

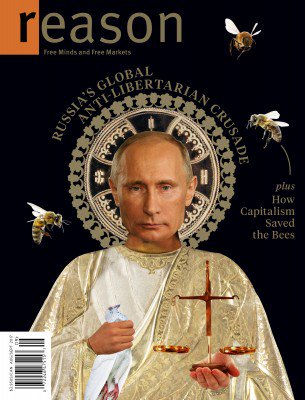

Fear and loathing of Russia is all the rage in Washington, D.C., as both liberal Democrats and neoconservative Republicans unite in a campaign to demonize the Kremlin as “the premier and most important threat, more so than ISIS,” as Sen. John McCain recently put it. While Hillary Clinton and her dead-ender supporters conjure a Vast Russian Conspiracy to hand the 2016 election to Donald Trump, and the neocons take advantage of this to push their longstanding hatred of Russian President Vladimir Putin, even ostensible libertarians are getting into the act.

This may seem counterintuitive: after all, the modern libertarian movement was born in rebellion against the cold war politics of the Vietnam war era, and libertarians have always opposed Washington’s interventionist foreign policy, such as NATO and a destabilizing and dangerous arms race. Yet even libertarians are not immune to the power of groupthink and the tyranny of political fashion, as the cover story in the most recent edition of Reasonmagazine makes all too clear.

Provocatively entitled “Russia’s Global Anti-Libertarian Crusade,” and authored by longtime Russophobe Cathy Young – herself an immigrant from Russia – the piece makes the case for viewing Russia in McCain-esque terms, i.e., an implacable enemy, the driving force behind an “illiberal international” dedicated to stamping out the last vestiges of liberty all across the globe. And it doesn’t stop there: Young advocates a series of measures to be undertaken by both governments and private entities to stem the “illiberal” tide – including economic sanctions against Russia. She writes:

Aside from a verbal commitment to liberal democracy and the rule of law, what can Western countries do to curb Russia’s anti-liberal influence without risking military conflict? Economic sanctions – particularly when they target the Russian political elite and its properties abroad, as opposed to targeting ordinary Russian consumers – can be more effective than they are often believed to be.

As Young and the editors of Reason know full well, existing sanctions against Russia are not limited to “the Russian political elite.” And, in any case, Young doesn’t object to these comprehensive restraints on trade: she wants them extended to include particular persons and institutions for the sole purpose of antagonizing them and making any sort of rapprochement between Russia and the United States impossible.

Which leads us to scratch our heads and ask: what’s up with a “libertarian” magazine pushing economic sanctions? What happened to “free trade” and untrammeled capitalism, supposedly the touchstones of the free market philosophy so energetically celebrated by Reason since its founding in 1969? Isn’t it odd that Reason opposes economic sanctions on Communist Cuba, but wants them slapped on Russia – which is just emerging from 70-some years of its Marxist nightmare? Perhaps one explanation is that the magazine is funded in large part by oil oligarch Charles Koch, of Koch Industries, who stands to make billions if Russian energy exports are blocked by government action.

While ascribing this motivation to the editors of Reason may seem uncharitable, it is the least uncharitable explanation for publishing Young’s farrago of falsehood, innuendo, and neo-McCarthyite rubbish. Far worse would be an ideological motivation: that they actually believe the pathetic conspiracy theory Young cobbles together out of the imaginings of various professional Russophobes.

While distancing herself from the “more extreme” anti-Russian narratives, which she admits are conspiracy theories with little evidence to support them, Young weaves a “moderate” conspiracy theory of her own – with just as little evidence to support it. She claims that the Russians are supporting the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party of Greece, and Hungary’s “quasi-fascist” Jobbik movement, although no evidence of this is presented. She says in several instances that the National Front party of France’s Marine Le Pen is a Russian front: her “evidence” is that a Russian bank with “links to the Kremlin” provided the party with a loan. One wonders if, say, a British bank (with undefined “links” to Westminster) loaned money to an America political party, would that make them a tool of Perfidious Albion?

Who needs actual evidence, anyway, when writing about Russia? After all, as computer security expert Jeffrey Carr points out, there is exactly zero public proof that the Russians “hacked” the 2016 elections – and yet the media “reports” this as undisputed fact.

Bereft of any actual facts, Young proceeds to assemble an ideological construct, one that, however, has some pretty big cracks in the foundations. To wit:

Cloaked in the mantle of religious and nationalist values, the Kremlin positions itself as a defender of tradition and sovereignty against the godless progressivism and the migrant hordes overtaking the West. It has a global propaganda machine and a network of political operatives dedicated to cultivating far-right and sometimes far-left groups in Europe and elsewhere.

How does one reconcile Russia’s alleged crusade against “godless progressivism” with their alleged support for “far-left groups in Russia and elsewhere”? She mentions Syriza, the Greek leftist party that briefly came to power. Leaving aside that Young nowhere documents this alleged support – not even with so much as a single link – it would seem more than a bit odd for the Kremlin, the supposed fountainhead of Orthodox Christianity, to be behind the success of the Greek Syriza party, which is militantly secular: a Syriza proposal to completely separate the Greek state from the Orthodox Church and levy a special tax on all church members would seem to contradict Young’s thesis. Are leftists now suddenly defenders of “tradition”?

Young’s hostility to Orthodox Christianity is one of the linchpins of her conspiracy theory: Putin’s support for Christian values, as viewed through the lens of Russian Orthodoxy, is depicted as a threat to the West. This is a curious argument to make, since Christianity – while in retreat in the West – is still seen as the basis of the Western individualist ethic, the foundation of the very same “liberal values” that Young extols throughout her essay.

She cites John Schindler, a former US Naval War College professor forced out for sending photos of his penis to a Twitter follower, in support of this contention. Schindler asserts that Edward Snowden is a Russian agent and that Glenn Greenwald, who reported on Snowden’s findings, was in it for the money. Young cites him as a credible authority, invoking his theory that Putin is engaged in “Orthodox Jihadism” against the West. It doesn’t matter that Putin’s “Orthodox jihadists” – Where are they? Who are they? – aren’t the ones planting bombs throughout Western Europe. They’re against gay marriage, aren’t they? Writes Young: “The main example of Western decadence and liberal extremism was, of course, same-sex marriage.” Case closed! Except that Schindler ridiculing Greenwald, who is gay, as “Glenda” seems to undercut Young’s depiction of the former Naval War College professor and NSA veteran as a champion of liberal tolerance. One also has to wonder what Young, an admirer of novelist Ayn Rand, makes of Schindler’s belief that Rand was a secret Russian agent.

Another building block of Young’s argument that Putin’s Russia is “authoritarian” and a danger to the West is Ivan Ilyin, an early twentieth century Russian writer whom she describes as an “authoritarian nationalist,” a designation that has little to do with his actual views. During his time as Russia’s chief executive, Putin has quoted Ilyin on exactly five occasions, and Young sees this as “telling” – but what exactly does it tell us?

When Ilyin was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1922, he went to Berlin, where he was forced out by the Nazis for the crime of failing to teach in accordance with the doctrines of National Socialism – an odd transgression for an “authoritarian nationalist” to have committed, but there you have it. While Young gives us a highly colored view of Ilyin’s politics, a more expansive – and fairer – synopsis is provided by Paul Robinson in The American Conservative:

Ilyin believed that the source of Russia’s problems was an insufficiently developed ‘legal consciousness’ (pravosoznanie). Given this, democracy was not a suitable form of government. He wrote that ‘at the head of the state there must be a single will.’ Russia needed a ‘united and strong state power, dictatorial in the scope of its powers.’ At the same time, there must be clear limits to these powers. The ruler must have popular support; organs of the state must be responsible and accountable; the principle of legality must be preserved and all persons must be equal under the law. Freedom of conscience, speech, and assembly must be guaranteed. Private property should be sacrosanct. Ilyin believed that the state should be supreme in those areas in which it had competence, but should stay entirely out of those areas in which it did not, such as private life and religion. Totalitarianism, he said, was ‘godless.’

That Putin isn’t presiding over a Jeffersonian republic is a complaint that fails to view modern Russia’s history in context. It wasn’t that long ago that Josef Stalin was sending millions to the Gulag, and a one-party totalitarian state reigned supreme in Russia and its satellites. Ilyin’s advocacy of a strong central state makes sense in the context of Putin’s task: dismantling a system from the top. (See libertarian economist Henry Hazlitt’s novel, Time Will Run Back, about a socialist dictator who decides to free up the system.)

Borrowing from the academic contingent of neo-Cold Warriors, such as Timothy Snyder, Young invokes the theories of one Alexander Dugin, an obscure Russian rightist whose philosophy of “Eurasianism” posits a struggle between a capitalist-globalist-universalist West intent on imposing its rule worldwide and a Russian-led resistance energized by traditionalism and Christian values. Undeterred by her own observation that Dugin’s influence is minimal, she goes on to link “Eurasianism” to the “global anti-libertarian crusade” that is supposedly a threat to our precious bodily fluids. Yet Dugin has next to no influence inside the Russian government, or within the body politic: he is a marginal figure. So what’s the big deal?

Young cites Montenegro as an example of an insidious Russian plot to overthrow “pro-Western” forces, but a simple look at the alleged coup supposedly attempted by a murky group of allegedly pro-Russian types shows that this is absolute bollocks. As the New York Times reported:

[Former Montenegro Prime Minster Milo] Djukanovic and his officials initially provided no evidence to support their allegation of a foiled coup attempt on Oct. 16, the day of national elections. They said only that 20 Serbs – some of whom turned out to be elderly and in ill health – had been detained just hours before they were to launch the alleged putsch. Nonetheless, Mr. Djukanovic insisted it ‘is more than obvious’ that unnamed ‘Russian structures’ were working with pro-Moscow politicians to derail the country’s efforts to join NATO.

Evidence? Who needs it? After all, we’re talking about Russia! Meanwhile, everyone supposedly involved in the “plot” has been released – except for leaders of the opposition party, who have been rounded up on suspicion of aiding the “plotters.”

You don’t have to be a neoconservative, says Young, in order to support “freedom friendly” countries, and if Russia “bullies” the Baltics, Georgia, and Ukraine into “returning to vassalage” it would be a “net loss for liberty” and for America.

To begin with, there is zero evidence that the Russians have any desire – or even the capacity – to retake the Baltics, for example. What they are concerned about, however – and what is completely off Young’s radar – is that ethnic Russians who live in Estonia, for one, and have lived there for generations exist in a legal limbo and are forbidden to vote in national elections. In his interviews with Oliver Stone, Putin points out that, with the sudden fall of the Soviet Union, millions of ethnic Russians woke up one day to find themselves outside their own country. Young, who left Russia at an early age, is indifferent to their fate.

More to the point, however, is that the social and political systems outside the United States which are less than Jeffersonian utopias have zero impact on the status or strength of our constitutional system and civil liberties in this country. What does have an impact is our policy toward these countries: if we engage in a cold war with Russia, and spend ourselves into oblivion in an arms race, risking war and even nuclear annihilation, America will itself become much less “freedom-friendly.”

The real point of Young’s elaborate conspiracy theory is to discredit anyone who challenges the narrative that a cold war with Russia is both inevitable and desirable. This means framing the debate – although there hasn’t really been a debate – in a certain way. She writes:

Pro-Russian (or at least anti-anti-Russian) arguments have become fairly common not just among conservatives but among a contingent of libertarians, such as former Rep. Ron Paul and Antiwar.com Editorial Director Justin Raimondo. The new Republican affection for Russia is largely a matter of political polarization: Since Putin is the Democrats’ boogeyman du jour, he can’t be all bad. But quite a few conservatives also genuinely see Putin’s Russia as a Christian ally against Islam, a perspective recently endorsed by Ann Coulter in a March column trollishly titled ‘Let’s Make Russia Our Sister Country.’

Young’s hostility to Christianity aside, what Young is attempting to do here is to define the debate in terms very similar to those employed by the neoconservatives during the run up to the Iraq war. If you opposed that war, you were “pro-Saddam” or “pro-Iraq”: if you supported it you were for installing a “freedom-friendly” regime in Baghdad.

This loading of the dice will not stand: the idea that opposing a new cold war with Russia makes one “pro-Russian” is nonsensical, unless “pro-Russian” means you don’t want to start World War III. Is it “pro-Russian” to point to the fact that the United States under George W. Bush and Bill Clinton unilaterally abrogated the ABM Treaty, and that this act fueled a new arms race and increased the risk of war? Is it “pro-Russian” to have opposed the expansion of NATO, which violated a verbal agreement between the first Bush administration and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev?

In Cathy Young’s World – right next door to Bizarro World – the answer is yes.

Opponents of a new cold war with Russia are neither pro-Russian nor fans of Vladimir Putin. They are simply advocates of a common sense approach to Russia, and to US foreign policy in general, which holds that America’s real interests lie in cooperation with the world’s largest nation insofar as that is possible.

If you oppose Cold War II, you are siding with Russia – this is the assumption at the heart of Young’s argument, and it is, simply put, a primitive lie. She writes:

Ron Paul–style libertarians are inclined to see Russia as a check on U.S. foreign adventurism and Russia hawks as hardcore proponents of the American imperial leviathan. ‘Unfortunately, there is a small contingent who fall victim to the fallacy that ‘the enemy of the enemy is my friend,’ and if the Kremlin is the enemy of my enemy, then it must be my friend,” [Cato Institute vice president and Atlas Network activist Tom] Palmer says.

The real fallacy is Palmer’s attempt to characterize libertarian opposition to the new cold war as evidence of active collaboration with and support for the Russian state – a smear similar to the one he frenetically propagated during the Iraq war (he opposed what he saw as “premature” US withdrawal), when he accused Antiwar.com and myself of supporting terrorism and advocating the death of US soldiers.

If Russia is “a check on US adventurism,” it isn’t doing a very good job, as demonstrated by the interventions in Syria, Libya, Iraq, Somalia, Afghanistan, etc. etc.

Although Palmer claims to be a libertarian, his Atlas Network has the endorsement of a US government agency, the National Endowment for Democracy, which is part of the “regime change” apparatus the US operates throughout the world. While it’s not clear if Atlas gets direct government funding, their personnel and activities are intertwined with the NED, and perhaps other government agencies. Two years after the invasion of Iraq, Palmer traveled to that country to attend a conference on “Advancing Women’s Rights: Two Years in Iraq” – a title that, given Iraq’s present state, cruelly mocks its sponsors down through the years. The conference – where Palmer lectured participants on “What is Democracy?” – was funded in part by the US government. He also addressed the Iraqi Parliament on the subject of their proposed constitution, which he praised in an op ed.

Now that Putin has taken the place of Saddam Hussein as the bogeyman of the moment, Palmer has taken up the cudgels against the Kremlin, traveling to Ukraine to support the corrupt kleptocracy of Petro Poroshenko and hailing the Ukrainian central government’s war on its own citizens. There he railed against the “red-brown homophobic racist bigoted movements” which Putin is supposedly behind. By the way, Franklin Templeton, a major investment firm, is Ukraine’s biggest private investor in government bonds: Templeton also contribute substantial amounts in the form of “Freedom Grants” to Palmer’s Atlas Network.

Just follow the money.

“Wouldn’t it be nice if we could get along with Russia?” President Trump said this repeatedly during the 2016 presidential campaign, and it enraged the foreign policy elites of both parties, who are banking their prestige – and their stock options – on a confrontation with Putin. The military-industrial complex, the national security bureaucracy, the out-of-fashion Kremlinologists who hope for new relevance in this age of renewed Russophobia, and, yes, the Cathy Youngs of this world – embittered Russian émigrés who carried their hate of the homeland with them in their suitcases – flipped out.

Trump’s victory was followed by an all-out offensive by these people, who built an elaborate conspiracy theory that claims Trump is a Russian agent, “Putin’s puppet,” as Hillary Clinton foolishly put it. The campaign to create a climate of anti-Russian hysteria, to the point where a US official meeting with the Russia ambassador is considered suspect, is well advanced, and the Young piece in Reason is part of this: the goal is to police the libertarian movement in order to expunge it of “pro-Russian” elements, such as myself and Ron Paul.

Well, good luck with that, Cathy: most libertarians – I’d say the overwhelming majority – are against the new cold war, and look with disdain on the ludicrous evidence-free antics of the Democrats and their neoconservative allies in the Never Trump camp to paint the President as a Russian sleeper agent. Of course, she’ll have more luck inside the Beltway, where the winds of conformism reach gale force – thus the editors of Reason put Young’s screed on their cover. Libertarian organizations inside the Beltway, such as the Cato Institute – which has been jumping on the Hate Russia bandwagon lately – cited in Young’s piece have become increasingly irrelevant as far as the grassroots libertarian movement is concerned. In that sense, Young’s attempt to smear such good libertarians as Ron Paul is merely virtue-signaling to the Beltway that the “mainstream” libertarians are going to go along with the current Russophobic hysteria, regardless of what us “extremists” may say or do.

The truth is, however, that the “small contingent” Palmer spoke of is a description of him and his fellow cold warriors, who represent nothing and no one but themselves and their wealthy donors. Our movement, the libertarian movement, was born in the midst of the cold war: we learned early on that the War Party is the greatest enemy of liberty, the adversary that must be defeated before we can get our old republic back. The crazed anti-Russian campaign now being waged by both the “left” and “right” wings of the War Party can only lead to a military conflict – a war that could annihilate us all. Somehow, I doubt that “Libertarians for World War III” is going to get much traction – but, hey, they’re trying!

Reprinted with permission from Antiwar.com.