This talk was delivered on November 9, 2019, at the Mises Institute symposium in Lake, Jackson, Texas.

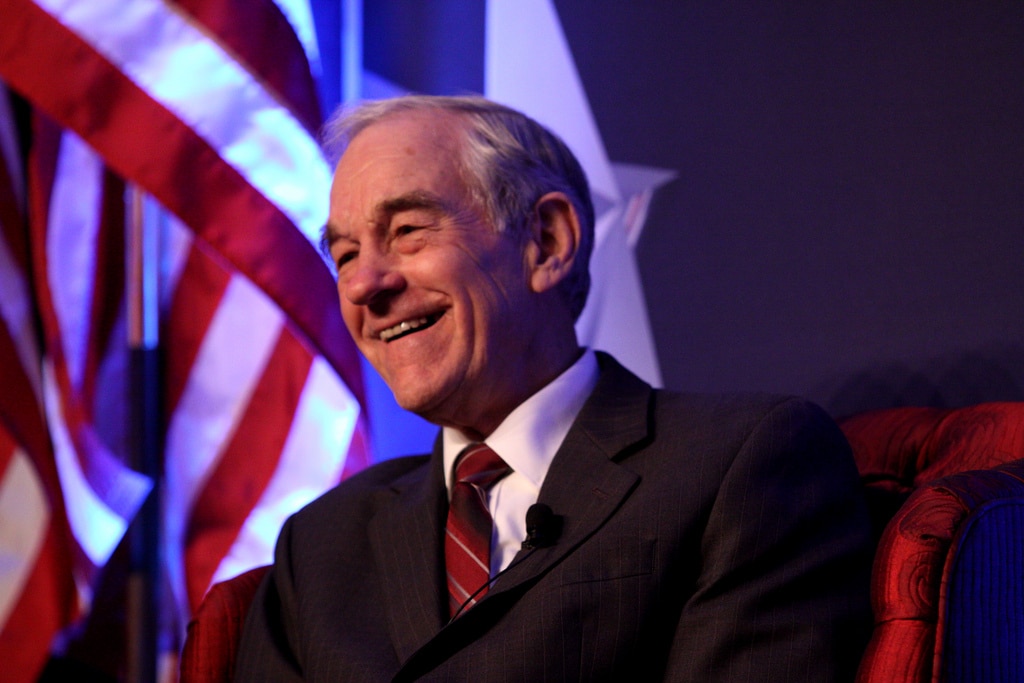

I had the rare honor of serving as Ron Paul’s congressional chief of staff, and observed him in many proud moments in those days, and in his presidential campaigns. People today sometimes compare Ron Paul with Bernie Sanders. The comparison of Bernie to Ron goes like this: both launched insurgent, anti-establishment presidential campaigns while in their 70s, shook up their respective party establishments, and attracted large youth followings. But Bernie is no Ron.

Just on the surface: Bernie is a grump and difficult to work with; Ron is a kindhearted gentleman who always showed his appreciation for the people in his office.

More importantly, Ron urged his followers to read and learn. Countless high school and college students began reading dense and difficult treatises in economics and political philosophy because Ron encouraged them to. Ron’s followers, meanwhile, were curious enough to dig beneath the surface. Is the state really a benign institution that can costlessly provide us whatever we might demand? Or might there be moral, economic, and political factors standing in the way of these utopian dreams?

It’s not hard to cultivate a raving band of people demanding other people’s things, as Bernie Sanders does. Such appeals arouse the basest aspects of our nature, and will always attract a crowd. It’s very hard, on the other hand, to build up an army of young people intellectually curious enough to read serious books and consider ideas that go beyond the conventional wisdom they learned in school about government and market. It’s hard to build up a movement of people whose moral sense is developed enough to recognize that barking demands and enforcing them with the state’s gun is the behavior of a thug, not a civilized person. And it’s hard to persuade people of the counter-intuitive idea that society runs better and individuals are more prosperous when no one is “in charge” at all.

Yet Ron accomplished all these things.

As the person who reached more people with the message of liberty than anyone in our time, Ron has also taught us how that message can and must be spread. I want to talk about five of these lessons.

First and foremost, Ron is a critic of the warfare state.#1 The subject of war cannot, and should not, be avoided.

Ron is not a pacifist – an ancient charge against those who oppose constant war. He believes in the right to self-defense, but he does not believe in the initiation of violence, whether by private criminals or the state. The state has recently taken more than a million lives in its imperialist anti-Muslim wars. Ron Paul has opposed them with all his heart and soul. He is a man of peace and the golden rule, in his private life and his policy.

The war in Iraq, which was still a live issue when Ron first ran for the Republican nomination, had been sold to the public on the basis of lies that were transparent and insulting even by the US government’s standards. The devastation – in terms of deaths, maimings, displacement, and sheer destruction – appalled every decent human being.

Yes, the Department of Education is an outrage, but it is nothing next to the horrifying images of what happened to the men, women, and children of Iraq. If he wasn’t going to denounce such a clear moral evil, Ron thought, what was the point of being in public life at all?

Still, this is the issue strategists would have had him avoid. Just talk about the budget, talk about the greatness of America, talk about whatever everyone else was talking about, and you’ll be fine. And, they neglected to add, forgotten.

But had Ron shied away from this issue, there would have been no Ron Paul Revolution. It was his courageous refusal to back down from certain unspeakable truths about the American role in the world that caused Americans, and especially students, to sit up and take notice.

Worried about the budget? You can’t run an empire on the cheap. Concerned about TSA groping, or government eavesdropping, or cameras trained on you? These are the inevitable policies of a hegemon. In case after case, Ron pointed to the connection between an imperial policy abroad and abuses and outrages at home.While still in his thirties, Murray Rothbard wrote privately that he was beginning to view war as “the key to the whole libertarian business.” Here is another way Ron Paul has been faithful to the Rothbardian tradition. Time after time, in interviews and public appearances, Ron has brought the questions posed to him back to the central issues of war and foreign policy.

Inspired by Ron, libertarians began to challenge conservatives by reminding them that war, after all, is the ultimate government program. War has it all: propaganda, censorship, spying, crony contracts, money printing, skyrocketing spending, debt creation, central planning, hubris – everything we associate with the worst interventions into the economy.

But Ron Paul permanently changed the nature of the discussion on war and foreign policy. The word “nonintervention” rarely appeared in foreign-policy discussions before 2007. Opposition to war was associated with anti-capitalist causes. That is no longer the case.

In exposing the fraudulent American foreign policy debate, Ron exposed an overlooked truth about American political life. The debates Americans are allowed to have are ones in which the real decisions have already been made: income tax or consumption tax, fiscal stimulus or monetary stimulus, sanctions or war, later war or war right away. With debates like these, it hardly matters who wins. Ron pulled back the curtain on all of it.Ron kept insisting that there was no real foreign policy debate in America because all we were allowed to do was argue over what kind of intervention the US government should pursue. Whether intervention itself was desirable, or whether the bipartisan assumptions behind US foreign policy were sound – this was not even mentioned, much less debated.

#2 Tell the truth.

It wasn’t just on war that Ron defied the censors of opinion. Ask Ron Paul a question, and you get an answer. In Miami he said the embargo on Cuba needed to be lifted. In South Carolina he stuck to his guns on the drug war. He never ran away from a question, or twisted it, in spin-doctor fashion, into the question he wished he had been asked.

And the audiences kept growing: thousands and thousands of students were coming out to see him, at a time when his competitors could barely fill half a bingo hall.

Ron knew that the philosophy of liberty, when explained persuasively and with conviction, had a universal appeal. Every group he spoke to heard a slightly different presentation of that message, as Ron showed how their particular concerns were addressed most effectively by a policy of freedom.

#3 The problem is not one person, nor one party.When Ron first spoke to the so-called values voters, for example, he was booed for saying he worshipped the Prince of Peace. The second time, when he again made a moral case for freedom, he brought the house down. But he did not pander to them nor to anyone else, and he never abandoned the philosophy that brought him into public life in the first place. No one had the sense that there was more than one Ron Paul, that he was trying to satisfy irreconcilable groups. There was one Ron Paul.

Ron rarely gets worked up about some government functionary who had been receiving some graft. Yes, this is wrong, and yes, the guy should be sacked.

But to spend inordinate time on the scandal of the day is to suggest that if only we had good people in charge, the system would work. The vast bulk of what the state does shouldn’t be done at all, with good or bad people, and whatever else it does can be far better managed by free individuals.

If a government official spends inordinate sums on vacations and luxuries, or is exposed for being on the take, be assured that the person’s political opponents will be all over the story. Meanwhile, the inherent corruption of the system itself, with its systematic expropriation and redistribution, is ignored. But that is by far the more important story, and it’s the only one that really deserves our attention.

Before leaving Washington and electoral politics, Ron delivered an extraordinary farewell address to Congress. The very fact that Ron could deliver a wise and learned address only goes to show he was no run-of-the-mill congressman, whose intellectual life is fulfilled by talking points and focus-group results.#4 There is more to life, and more to liberty, than politics.

That a farewell address seemed so appropriate for Ron in the first place, while it would have been risible for virtually any of his colleagues, reflected Ron’s substance and seriousness as a thinker and as a man.

In that address Ron did many things. He surveyed his many years in Congress. He made a reckoning of the advance of the state and the retreat of liberty. He explained the moral ideas at the root of the libertarian message: nonaggression and freedom. He posed a series of questions about the US government and American society that are hardly ever asked, much less answered. And he gave his supporters advice on spreading the message in the coming years.

“Achieving legislative power and political influence,” he said,

should not be our goal. Most of the change, if it is to come, will not come from the politicians, but rather from individuals, family, friends, intellectual leaders, and our religious institutions. The solution can only come from rejecting the use of coercion, compulsion, government commands, and aggressive force, to mold social and economic behavior.

No focus groups urged Ron to talk about the Federal Reserve. No politician had made an issue of the Fed in an election in its 100-year history. Stick to the script, the professionals would have said: lower taxes and lower spending, the monotonous refrain uttered by every Republican politician, who typically has no interest in carrying through with either one anyway.#5 The Fed cannot be ignored.

Here again, had Ron adopted conventional political advice, he would have forfeited these historic moments and the Ron Paul phenomenon would not have been greatly diminished, if not compromised altogether.Yet Ron pointed to the Fed as the source of the boom-bust cycle that has harmed so many Americans. His dogged insistence on this point got a great many Americans curious: what, after all, was the Fed, and what was it up to? An unlikely issue, to be sure, and yet it was his willingness to talk about it that in my view helps to account for much of his fundraising success. There was a small but untapped portion of the public that responded with enthusiasm to Ron’s very mention of the Fed, and they wanted more.

Only a few months after Ron officially suspended his 2008 campaign, the financial crisis struck. Just as Ron had said, there was something indeed wrong with the economy.

Because he hadn’t hesitated to say what he believed, even if it meant dealing with an issue no political operative would have encouraged him to discuss, Ron was a prophet. That point alone opened countless more people to Ron’s ideas: here was the only guy in Washington who warned us of what was to come. (And incidentally, has there been a time in American history in which more people were reading – and writing! – anti-Fed books?)

People could see, too, that Ron hadn’t just gotten lucky in 2007 and 2008. In 2001, Ron said on the House floor that the Fed-fueled bubble in tech stocks, which had just burst, was being replaced by a Fed-fueled real-estate bubble, which would burst just as surely.

Of course, it’s not enough just to get rid of the Fed, essential as that is. We need sound money, and for Ron, following Mises and Rothbard, this means the gold standard. Once, when our Ron was invited on the other Ron’s Air Force One for a flight to Houston, Ron Paul commented on Reagan’s watch, which was made from a $20 gold piece. “I wish we still had that monetary system,” said Ron Paul. “You know, no nation that abandoned the gold standard has remained great,” said Reagan. Don Regan told the president to drop the subject.

In 1982, Ron Paul served on the US Gold Commission to evaluate the role of gold in the monetary system. In fact, the Commission was his idea. It was carrying forth a promise made in the Republican platform.

Ron couldn’t pick the members, so from the beginning, the deck was stacked. The majority was dominated by monetarists, who saw gold as too scarce and paper as just fine. Ron Paul’s team was ready, however, with this marvelous minority report.

Rarely has a dissent on a government commission done so much good!

The result was The Case for Gold, and it was the greatest result of the commission. It covers the history of gold in the United States, explains that its breakdown was caused by governments, and explains the merit of having sound money: prices reflect market realities, government stays in check, and the people retain their freedom.

The scholarship and rigor impressed even the critics of the minority. Ron and Lewis Lehrman worked with a team of economists that included Murray Rothbard, who was the main author, so it is hardly surprising that such a book would result.

I am convinced that historians, whether or not they agree with him, will continue to marvel at Ron Paul for many, many years to come. Libertarians a century from now will be in disbelief at the very notion that such a man actually served in the US Congress of our time.

One of the most thrilling memories of the 2012 campaign was the sight of those huge crowds who came out to see Ron. His competitors, meanwhile, couldn’t fill half a Starbucks. When I worked as Ron’s chief of staff in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I could only dream of such a day.

Now what was it that attracted all these people to Ron Paul? He didn’t offer his followers a spot on the federal gravy train. He didn’t pass some phony bill. In fact, he didn’t do any of the things we associate with politicians. What his supporters love about him has nothing to do with politics at all.

Ron is the anti-politician. He tells unfashionable truths, educates rather than flatters the public, and stands up for principle even when the whole world is arrayed against him.

Of course, Ron Paul deserves the Nobel Peace Prize. In a just world, he would also win the Medal of Freedom, and all the honors for which a man in his position is eligible.

But history is littered with forgotten politicians who earned piles of awards handed out by other politicians. What matters to Ron more than all the honors and ceremonies in the world is all of you, and your commitment to the immortal ideas he has championed all his life.

It’s Ron’s truth-telling and his urge to educate the public that should inspire us as we carry on into the future.

Little did he know that those thankless years of pointing out the State’s lies and refusing to be absorbed into the Blob would in fact make him a hero one day. To see Ron speaking to many thousands of cheering kids, when all the while respectable opinion had been warning them to stay far away from this dangerous man, is more gratifying and encouraging than I can say. I was especially thrilled when a tempestuous Ron, responding to the Establishment’s description of his campaign as “dangerous,” said, you’re darn right — I am dangerous, to them.

Even the mainstream media has to acknowledge the existence of a whole new category of thinker: one that is antiwar, anti-Fed, anti-police state, and pro-market. The libertarian view is even on the map of those who despise it. That, too, is Ron’s doing.

Young people are reading major treatises in economics and philosophy because Ron Paul recommended them. Who else in public life can come close to saying that?

No politician is going to trick the public into embracing liberty, even if liberty were his true goal and not just a word he uses in fundraising letters. For liberty to advance, a critical mass of the public has to understand and support it. That doesn’t have to mean a majority, or even anywhere near it. But some baseline of support has to exist.

That is why Ron Paul’s work is so important and so lasting.

Reprinted with permission from LewRockwell.com.