Two summers ago Judge Andrew Napolitano joined the faculty of Mises University, the Mises Institute’s summer program for students. He was interested in teaching a nine-session special seminar to a select group of attendees. Students didn’t know what the format would be, but they were all thrilled at the opportunity. As it turns out, they were treated to a high-level seminar with a professor who spoke with authority, pulled out obscure legal references without notes, and traversed the room interacting with students. It was an experience they would not soon forget.

And this is the Judge Napolitano who comes through in Suicide Pact: The Radical Expansion of Presidential Powers and the Assault on Civil Liberties: the law professor in command of his material, presenting his case, anticipating objections, and leaving his audience spellbound.

Had the Judge given us nothing but a blow-by-blow overview of the enormities of George W. Bush and Barack Obama, we would have been in his debt. But Suicide Pact does much more than just this. For one thing, the Judge looks beyond the presidents to the whole federal apparatus, which – “checks and balances” civics lessons to the contrary notwithstanding – is so often complicit in presidential misdeeds. For another, he cuts through the delusions of left and right alike. While he places special emphasis on the outrages of the past two presidential administrations, he will admit of no golden-age mythology. Presidential crimes and overreach are not strange aberrations, explains the Judge. They extend back into American history for more than two hundred years.

Not ten years after the ratification of the Constitution, for example, the Alien and Sedition Acts curtailed civil liberties to a degree that shocks us even today. Critics of the president and Congress could find themselves fined or imprisoned. Ordinary Americans were punished for offhand remarks, as were newspaper writers and even a US congressman from Vermont.

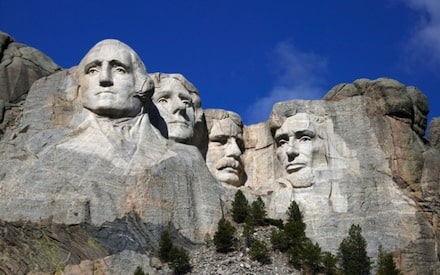

But some of the greatest offenders turn out to be – who else? – the very presidents schoolchildren are traditionally taught to revere. Violations of American liberty carried out by the likes of Abraham Lincoln, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt have in turn been gleefully embraced in the 21st century as precedents for the various presidential enormities Americans have become conditioned to accept as normal.

The Judge discusses, among other things, Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus and use of military commissions when civilian courts were still functioning. He covers the key cases: Ex parte Merryman, Ex parte Vallandigham (which involved the deportation of a US congressman from Ohio who opposed the war), and Ex parte Milligan. In other words, the book is a course in major episodes in American legal history, with the Judge as your professor.

Woodrow Wilson, another president admired by the historians, has his own list of outrages. We know about the Federal Reserve and World War I, of course, but presidential and federal power increased in other important ways as well. Wilson was given sweeping control over the economy via the Overman Act, for example. That was one of the reasons “progressives” supported the war: they knew it would mean more government power over individuals and their property. Wilson likewise presided over restrictions on free speech that seem incredible to modern ears: people imprisoned for giving speeches or writing small-circulation pamphlets, German-Americans intimidated and harassed, and an official channel of propaganda dissemination, the Committee on Public Information, making sure Americans understood the official line on world events.

In his discussion of Wilson, by the way, the Judge characteristically refuses to confine himself only to complaints that will resonate with a right-wing audience. He also covers the Red Scare, the Palmer Raids, and the deportations under the Alien Act of 1918. (That Act provided that any alien anarchist, whether or not he favored peaceful methods, could be deported; the process took place without counsel, jury, or judge.)

The Judge’s story continues through World War II, a period in which we seldom hear about the fate of American liberty. We read in Suicide Pact about domestic spying and the seldom mentioned curtailments on economic liberty during the war. The internment of the Japanese is of course the most arresting example of a presidential enormity, and one that FDR’s admirers in the historical profession have so often downplayed as a curious and unfortunate footnote to an otherwise wonderful presidential tenure. As the Judge puts it, FDR ordered “a massive rights deprivation to placate a hysterical public whose hysteria his agents flamed, and upon which he capitalized so as to enhance presidential power.”

During the Korean War Harry Truman seized the steel mills, citing his commander-in-chief powers. In the Youngstown case, the Supreme Court ruled against Truman, but on procedural grounds: Congress rather than the president should have seized the private property. And even this was a rare display of boldness for the Court: Judge Napolitano notes that Youngstown was “the only presidential executive order ever overturned in its entirety by the United States Supreme Court,” and that “lower courts have struck down only two other presidential directives.”

Younger readers may not recall the matter of COINTELPRO, a program begun in secret by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in 1956 to keep tabs on dissident organizations. Neither the president nor the attorney general knew anything about the program. COINTELPRO had a systematic strategy:

1) Gathering information;

2) Crafting a negative public image of the targeted group;

3) Interfering with the group’s internal structure;

4) Instigating internal fighting and disagreement;

5) Limiting the group’s access to public resources;

6) Constraining protest and assembly abilities;

7) Interfering with specific individuals and their ability to participate in the group.

It probably goes without saying that the details of the program were not revealed to the public by a congressional investigation or a New York Times report. A group called Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI, which was itself being investigated by COINTELPRO, broke into the FBI’s field office and got hold of confidential documents describing the program in detail. It was officially discontinued, though of course no government officials were criminally prosecuted. Along with the revelations about government surveillance under George W. Bush and Barack Obama, it serves as a salutary reminder that whatever we know about government activity likely pales beside what we don’t know.

All this historical material is by way of background, context, and introduction to the more recent expansions of presidential power in the wake of the war on terror, and here I simply urge you to read the Judge for yourself. The right wing, full of righteous rage at the imperial Obama, managed to look the other way while George W. Bush expanded federal power, and his own in particular, throughout two presidential terms.

Not so Judge Napolitano. The PATRIOT Act, warrantless wiretapping, renditions, torture, drones, military commissions, Guantanamo – the whole apparatus of the war on terror is laid out in detail here, complete with background, analysis, and criticism. Here is the systematic case against the prosecution of the war on terror on the domestic front. And it again invites the question: if we know all these things are happening, what else is happening that we don’t know?

Everyone knows the Judge is an outstanding television personality, a captivating public speaker, and a persuasive writer, but Suicide Pact establishes him once and for all as an important scholar of American history and law. The book, which carries the story up to 2013, doesn’t have a happy ending, of course. But that story isn’t yet finished, and when liberty makes its return, we will have the likes of Judge Napolitano to thank. When others in his position were toadies of the regime, he was telling unfashionable truths to an American public that often prefers the comfortable lie.

Reprinted with permission from LewRockwell.com.