In 1974, when Friedrich Hayek won the Nobel Prize in Economics, he used his acceptance speech to deliver a warning to the world. Do not again fall for “the pretense of knowledge,” he counseled.

Hayek was singling out economic policymakers who presume to possess the knowledge needed to confidently predict and design market outcomes, much as engineers precisely predict and design mechanical outcomes.

Yet, as Hayek surely recognized, such epistemic arrogance is rampant throughout all social thought, and not just economics. It particularly plagues the realm of foreign policy.

Consider how impossible it is to know exactly what is going on in anyone else’s mind. Nobody can predict with certainty an individual’s future choices, and the preferences those choices reveal. The mind of even a single person is to a great degree opaque. Now take that opacity and multiply it by the millions of minds that make up an economy or a country. That is a hell of a lot of ignorance and unpredictability.

Add to this the manifold nature of the material world in which we live. Then contemplate the fluctuating and elaborate interplay of all those minds and materials. Only then do you begin to realize how unfathomably complex the social world is, and the absurdity of anyone thinking they can engineer society.

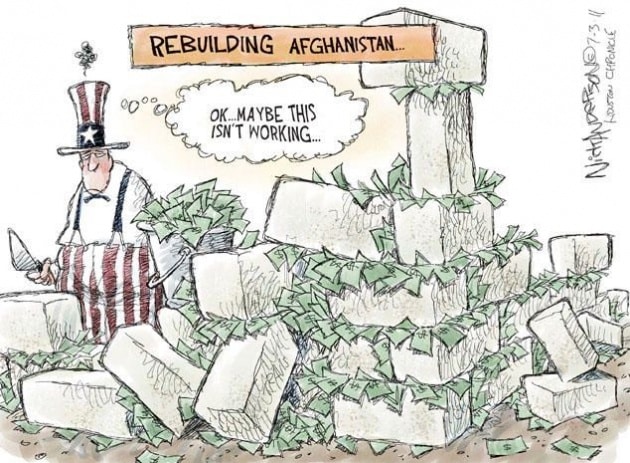

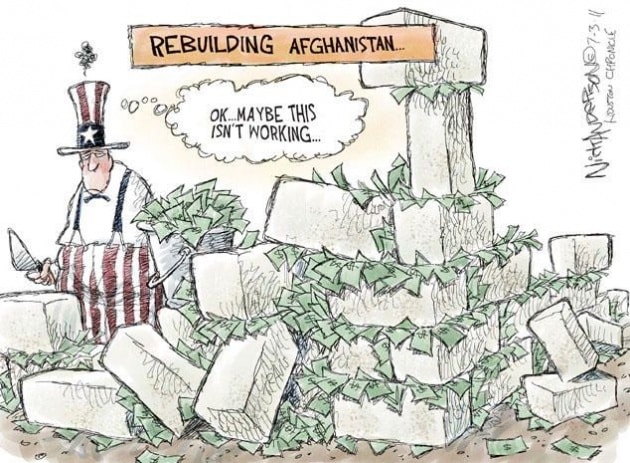

Foreign policy planners are particularly prone to this kind of hubris. They are infatuated with the belief that they can whip a country, a region, even the whole world, into shape through the judicious application of extreme violence. This faith is impervious to mounting evidence to the contrary. Consider, for example, recent US foreign policy.

The Bush administration neocons guaranteed that regime change in Afghanistan and Iraq would be the first steps toward remaking the Greater Middle East with the blessings of freedom and democracy.

No sooner had the neocons covered themselves with failure than they were superseded by devotees of the counterinsurgency doctrine, or COIN. This doctrine was nothing more than a warmed over retread of the “hearts and minds” hooey of the Vietnam era. Yet the COIN peddlers did have one strategic success: capturing the hearts and minds of the foreign policy wonks in DC and Arlington. The Democratic-oriented COINsters proved just as arrogant as the Republican neocons, boasting that they could “change entire societies” and that they had a “government in a box” to bestow upon the benighted people living under their occupation.

No sooner had the COIN crowd been disgraced in turn than they were eclipsed by the Obama administration’s champions of the “Responsibility to Protect” doctrine, or R2P. Following the 2011 inception of the Arab Spring rebellions, R2P was a leading justification in Washington for regime change operations in Libya and Syria. These efforts focused on regime decapitation and have largely eschewed nation-building. Yet even their more modest goals proved unattainable. The R2Pers did not head off, but only precipitated humanitarian disasters. Somehow flooding countries with weaponry and jihadist recruits turned out not to have a salutary effect on civil society.

After all these invasions, “surges,” and interventions, the Greater Middle East has been “remade” alright, into a cauldron of collapse, chaos, and carnage. Yet, unperturbed, Western planners continue to dream up new schemes for the region.

Even if their stated intentions were genuine, these geopolitical planners could not have succeeded and never will. It is foolish enough for domestic governments to think they are capable of “remaking society.” It is an even greater folly for foreign governments to think so.

This is because foreign planners are in an even worse position than domestic ones when it comes to “local knowledge,” or what Hayek referred to as “the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place.”

Hayek stressed the importance of local knowledge in the context of an economy. In his classic essay on the subject, he argued that it is impossible for a central planner to access and integrate all the relevant knowledge that is dispersed throughout the minds of individuals in society. And it is only through such an integration of the untold billions of bits of local knowledge that a complex economy can be rationally coordinated. Hayek added that:

The problem which we meet here is by no means peculiar to economics but arises in connection with nearly all truly social phenomena…

And so nation builders are just as helpless in the face of this “knowledge problem” as economic central planners. Just as with the production of anything else, there are innumerable local circumstances relevant to the production of peace and security, which is ostensibly the business of governance.

What are the tribal dynamics of this province? What are the sectarian dynamics of that town? Who are the pillars of this neighborhood community? What are the security needs of that family business? Local knowledge like this is crucial to navigate the multitude of adjustments and compromises necessary for avoiding civil strife. The military intelligence officer likes to fancy himself a quick study when it comes to these affairs. But his stunning rate of failure belies not only his incompetence and his perverse incentives, but the overwhelming nature of the challenge for any outsider.

De-Baathification. The marginalization of Muqtada al-Sadr. Drone-striking tribal leaders working for order and reconciliation in countries from Somalia to Pakistan. If military planners can’t avoid such obvious unforced errors as these, what chance do they have against more subtle problems?

It is no wonder then, that US intervention has fomented and fueled sectarian and tribal civil wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, Yemen, Somalia, Pakistan, and elsewhere. The expertise of America’s geopolitical planners has proven to be, not in the building of nations, but in the demolition of societies.

What is the alternative? According to Hayek, the market society manages to handle the knowledge problem in two ways. The first is through decentralization. Hayek wrote:

We need decentralization because only thus can we insure that the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place will be promptly used.

The second is the market price system, which performs the essential (and amazing) function of communicating local knowledge from throughout the economy to every market participant and meaningfully integrates it into his/her decision-making process.

Ideally, judicial and security services should also be left wholly to the market and to other purely voluntary institutions of civil society. Then, the provision of peace and justice would be responsible, service-oriented, and responsive to variations in local circumstances and needs.

But failing that, the next best thing would be maximum decentralization and devolution in governance. The more familiar a ruler is with local circumstances, the less monumental will be his blunders. Foreigners ruling Middle Eastern neighborhoods from “green zones” and other garrison outposts according to diktats sent by detached and self-absorbed politicos residing in the imperial capital of the West is the exact opposite of what’s needed.

Another name Hayek had for the pretense of knowledge was, “the fatal conceit.” The numberless victims of geopolitical planners are a grim testimony to just how fatal that conceit can be.

Reprinted with permission from Antiwar.com.