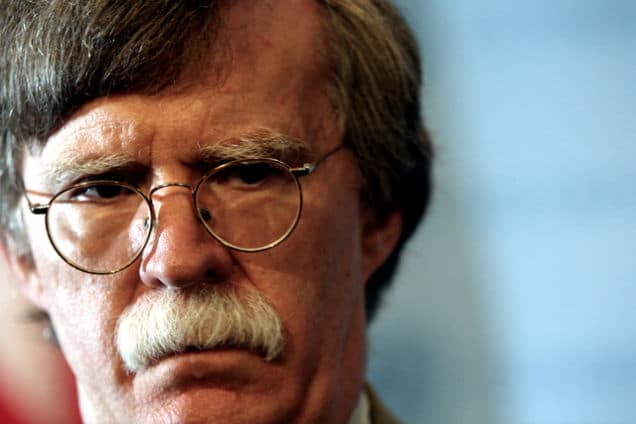

“We’re not looking for regime change [in Iran]. I want to make that clear,” President Trump said Monday at a news conference in Japan, “nobody wants to see terrible things happen, especially me.” That’s good to hear, but has Trump’s National Security Advisor gotten the message?

It’s the undeterrable John Bolton, after all, who’s been at the epicenter of the rumors of war plaguing Washington in recent weeks. It’s Bolton who ordered up a Pentagon plan for “retaliatory and offensive options” to check Iran, including a 120,000 troop surge to the region, and Bolton who blustered that a recent carrier-strike-group deployment signaled America’s willingness to meet any Iranian challenge with “unrelenting force.”

Trump is said to be frustrated by his aide’s brinksmanship, privately cracking that “if it was up to John, we’d be in four wars now.” “In recent days,” the New York Times reports this morning, “the disconnect between Mr. Trump and his national security adviser has spilled over into public,” with the president undercutting Bolton on Iran and North Korea. But Bolton still has his job. Ironically enough, it turns out that the longtime “Apprentice” host is gun-shy about firing people.

Is there anything Congress can do about a rogue presidential appointee that the president won’t fire? The progressive foreign-policy group Win Without War has an interesting proposal: they’re running a petition drive: “Tell Congress: Impeach John Bolton!”

Can Bolton be impeached? The answer turns on whether the National Security Advisor is one of the “civil Officers of the United States” to which Article II, sec. 4 applies. The term isn’t defined in the Constitution, and there’s little precedent to go on, the House having impeached just one executive-branch official below the presidential level in 230 years: Gilded-Age Secretary of War William Belknap. As the Congressional Research Service notes, it’s something of an open question “whether Congress may impeach and remove subordinate, non-Cabinet level executive branch officials.”

Still, the fact that Bolton, unlike a Cabinet secretary, doesn’t hold a Senate-confirmed position is a technicality that shouldn’t protect him, especially when it’s clear—even to the president—that his recklessness might drag us into an unnecessary war. Impeachment arose in England as a means of striking ministers close to the Crown, including those who gave “pernicious” foreign policy advice. Early American constitutional commentators like William Rawle and Justice Joseph Story believed the power extended to “all” federal executive officers. And as James Madison explained in the first Congress: “If an unworthy man be continued in office by an unworthy president, the house of representatives can at any time impeach [that officer], and the senate can remove him.”

In practice, it’s rarely been necessary to go that far. “The issue has almost invariably proven moot,” Frank Bowman explains in his comprehensive new volume High Crimes and Misdemeanors: A History of Impeachment for the Age of Trump. Historically, “any appointee whose continued service was so politically toxic as to provoke a serious effort at impeachment has been shuffled off the stage” when the president demands his or her resignation.

A resolution to impeach Bolton, something any member of the House could introduce, might serve as the shot across the bow that convinces Trump it’s time to clean his own house. It needn’t make it to the floor to be effective: merely securing enough cosponsors could be enough. On the other hand, such a move might cause Trump to dig in his heels—with a president this mercurial it’s hard to tell.

However, there’s another way Congress can use the threat of impeachment to deter an illegal and unnecessary war. As I explained in the American Conservative last week, the House could pass a simple resolution “expressing the sense of the House of Representatives that the use of offensive military force against Iran without prior and clear authorization of an Act of Congress constitutes an impeachable high crime and misdemeanor under article II, section 4 of the Constitution.”

The late, great Rep. Walter Jones (R-NC) proposed a similar measure in President Obama’s second term, when the administration publicly contemplated airstrikes on Syria. Jones introduced a concurrent resolution stating that “except in response to an actual or imminent attack against the territory of the United States, the use of offensive military force by a President without prior and clear authorization of an Act of Congress” is an impeachable offense. The Jones resolution only secured a handful of cosponsors and proved unnecessary when President Obama decided to seek congressional authorization for airstrikes, then abandoned the effort entirely.

Last summer, Jones and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI) revived the idea of pre-defining unauthorized warmaking as an impeachable offense. On the theory that “the law should warn before it strikes,” House Resolution 922 defined undeclared wars as high crimes and misdemeanors under Article II, section 4. Constitutional lawyer Bruce Fein, who originally proposed the idea and helped draft the bill, described its chances of passing as “remote in the short run. Its immediate purpose is to spark a public and congressional debate about war powers.”

The prospect of war with Iran ought to be all the spark that’s needed. As Gabbard recently noted, the conflict Bolton covets would make the Iraq War “look like a cakewalk—[it] would take far more American lives, it would cost more civilian lives across the region.”

The current House leadership fears that an impeachment drive would be a “divisive” distraction. Instead, Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) told House Democrats last week, “we need to show [voters] that we are doing all of these other things that they care about so much” (whatever those are). Pelosi may be right to worry about the political costs of an all-consuming impeachment effort in the run-up to the 2020 election. But a resolution along the lines proposed by Jones and Gabbard doesn’t open an impeachment inquiry. It wouldn’t distract and shouldn’t divide–unless one considers it “divisive” for Congress to defend its core prerogatives and head off an illegal war.

True, a sense of the House resolution wouldn’t have the force of law: it’s a mere statement of intent by the members who sign on. But it could serve as fair warning to the president, and a precommitment device for the House: a public pledge to take action should the administration cross the line. In politics as in war, deterrence sometimes requires a credible threat.

Reprinted with permission from Cato.org.