The Greek crisis is dominating headlines this week, and promises to be the most important economic and financial topic of conversation through the weekend and into Monday. Neither the Greek government nor the European Central Bank (ECB) seem to be prepared to give an inch, and there’s every indication that things could come to head next week. If Greece does default, and if there is a resulting crisis in European markets, will the Federal Reserve get involved? To quote Sarah Palin, “You betcha!” How would the Fed do this? Read on to find out.

Although the euro is the dominant currency in Europe, a lot of debt in Europe is still denominated in dollars. The dollar being the world’s reserve currency and dollar markets being incredibly liquid, it just makes sense for a lot of companies to do business in dollars. But when a crisis hits and those businesses need dollars, they have to get a hold of dollars somehow. Banks in Europe have a limited supply, and once those dollars are gone, there is no dollar-printing central bank in Europe that can step in. Enter the Federal Reserve.

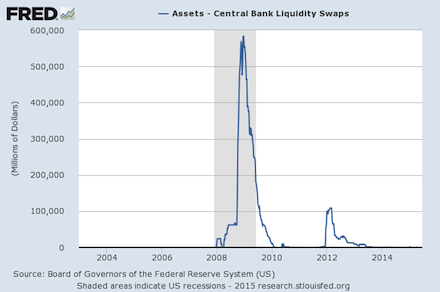

The Fed sets up liquidity swap lines with the ECB. These swap lines were, for many years, not highly publicized, and not even broken out as a separate category on the Fed’s balance sheet. That is, until the financial crisis hit and the swap lines rose to close to $600 billion. Even since the financial crisis they remain open, are periodically renewed, and occasionally still used, without much publicity.

A swap line is an agreement between the Fed and a foreign central bank to swap currency. For instance, the Fed creates new dollars, the ECB creates new euros, and they agree to exchange them. For the period of the swap, the Fed holds those newly-created euros as an asset, and the ECB loans those dollars out to firms that need dollars to make dollar-denominated payments. Presumably those firms are only in need of short-term dollar financing, and can pay those loans back. When the swap unwinds, the ECB then sends those dollars back to the Fed, the Fed returns the euros to the ECB, and the swap lines are drawn back down to zero. Sounds nice and easy, until there’s a problem.

Of course, there are many problems with swap lines. The inflationary effects of creating that new money and loaning it temporarily, the deflationary effects as it gets sucked back out of the system, and of course the fact that the central bank is picking winners and losers by determining which companies get to borrow those dollars. And those are just the problems when it is individual companies that are in danger of failing. Now we have an entire nation (Greece) that is in danger of failure, a nation that is in a currency union with all the other Eurozone countries. So what happens when (or if?) Greece implodes?

This drama has been going on for months, so maybe the big players have already minimized their exposure to Greece. Fed Chairman Janet Yellen seemed to downplay the importance of Greece when she was asked about it at her press conference on Wednesday. But what if this is a bigger problem than anyone realizes? I still remember getting called to a staff briefing in mid-2007, almost exactly eight years ago now, where committee staff on the House Financial Services Committee informed us that a little-known unit of Bear Stearns had gotten itself into a little bit of difficulty. Nobody seemed to think it was a terribly important issue, but they were going to monitor things. Little did we know that that incident was the harbinger of the financial crisis. Over the next year things went from bad, to worse, to catastrophic. It started small, but snowballed tremendously.

Now back to the swap lines. If you want to get a sense of the Fed’s involvement in Europe, watch the swap lines. Swap line data is published every Thursday afternoon on the Fed’s balance sheet, the H.4.1 release. If you look at the St. Louis Fed’s charts and data on swap lines, you’ll see the huge amount of swaps during the financial crisis, and then a smaller but still significant increase in swap lines during the first iteration of the Greek financial crisis back in 2012. While swaps have been relatively non-existent this year, there was a small blip back in April, likely Greek-related, and more importantly, another blip this week. While the amount, $114 million, is a drop in the bucket compared to what it has been in the past, this number needs to be watched. It could very well be an indicator of the Fed getting involved in Europe again. And if the doomsday scenario ends up taking place next week, expect that $114 million figure to skyrocket. The Fed seems to want the conversation to revolve around a possible upcoming interest rate hike, so it’s been relatively silent on the topic of Greece and its involvement in bailing out Europe. But even if the Fed doesn’t say anything about Greece, its money-printing to pump up the swap lines will do plenty of talking.

Reprinted with permission from the Carl Menger Center.