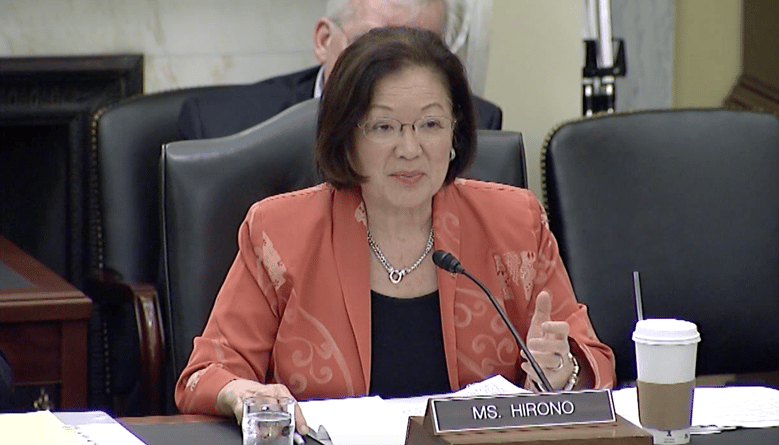

With the addition of a second woman alleging sexual misconduct of Brett Kavanaugh, it is still not clear what factual disputes will have to be addressed before a final confirmation vote occurs in the Senate. Putting aside questions over late timing of the allegations, there is agreement that the Senate will have to consider both the allegations of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and the new allegations of Deborah Ramirez. What is far more troubling is the continued disagreement on the standard that Senators should use in considering the allegations. While objecting that their Republican colleagues are not prepared to give the women an “impartial hearing,” various Democratic senators have declared (before any testimony is heard) that they believe Dr. Ford – and thus do not believe Judge Kavanaugh. That is troubling enough, but Sen. Mazie Hirono (D., HI) has introduced a far more troubling element in suggesting that she may decide the factual question on the basis of Kavanaugh’s jurisprudential views.

Hirono has previously declared that she believes Ford even before hearing either in testimony before the Committee. She also told all men everywhere to “shut up” and just stand with Ford. In her latest interview, Hirono was pressed on whether Kavanaugh has “the same presumption of innocence as anyone else in America?” For most people, the question would be an easy one to answer in the affirmative, Hirono demurred and declined to say that she would afford Kavanaugh this core presumption of the rule of law. She said that she would “put his denial in the context of everything that I know about him in terms of how he approaches his cases.” She said that she would consider his “ideological agenda” and her view that “he very much is against women’s reproductive choice.”

Hirono’s mixing of factual with ideological considerations further degrades a process that is already deeply undermined by last minute allegations and partisan bickering. It is also curious to see a senator tie credibility on sexual misconduct to one’s view of Roe v. Wade. Bill Clinton, Harvey Weinstein, Matt Lauer, Al Franken and others were all reportedly pro-choice but also labeled as abusers.

Such a reference to an accused’s political or ideological views by a judge would be viewed as the basis for a mandatory recusal for bias. It is entirely immaterial how one views constitutional rights in whether they should be believed in denying the commission of a crime.

There was, of course, a time when such a presumption of guilt on the basis for religion or nationality or other characteristics was an accepted (even celebrated) practice. During the Spanish Inquisition, who you were would determine whether you would be believed. It was not just suspected Jews but others like foreigners who faced an effective presumption of guilt. When Pedro Ginesta, an elderly man from France was arrested in 1635 for eating bacon on a day of abstinence, the indictment declared “The said prisoner being of a nation infected with heresy [France], it is presumed” that he is lying and part of “the sect of Luther.”

France for its part had the same difficulty with separating politics from law. During the French Revolution, the Law of Suspects was passed in 1793 relieving tribunals of the burden of minimal evidence in ordering arrests and any perceived counter-revolutionary views was enough to be indicted. Jacobins saw law and politics as inextricably linked. Of course, the desire to use legal or legislative means to punish political opponents becomes an insatiable appetite. One year later, the tribunals passed the Law of 22 Prairial, which stripped away remaining protections for the accused and allowed juries to convict on the ambiguous basis of “moral certainty.”

Hirono’s description of her approach comes dangerously close to the Jacobin use of “moral certainty” in judging facts. If Kavanaugh’s opposition to Roe can be used to subject him to a higher burden, would Weinstein’s support of Roe afford him a lower burden of proof?

It is not enough for Democratic Senators to simply say that they are not judges and therefore entitled to any standard of review no matter how pre-determined or unfair. Members of Congress do not have license to mete out punishments and judgments without due process to citizens. The Framers expressly barred Congress from passing “bills of attainder” – legislation that effectively singles out individuals or groups for special punishment for perceived offenses. Likewise, committees are subject to individual constitutional rights including the right against self-incrimination and other constitutional protections. In other words, there are rules.

More importantly, there are principles. When a member swears to uphold the Constitution, they agree to respect our defining values and protections. One of the most central protections is to be allowed a fair hearing. This is particularly the case when someone is accused of a heinous criminal act.

Unfortunately, “moral certainty” appears to be the growing standard for members who are rushing to assure voters on both sides that they are respective locks for either Ford or Kavanaugh. Proof then becomes a simple political head count. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) has even declared that he expects that, if Kavanaugh is confirmed, a Democratic majority would launch an immediate investigation and possible impeachment against him as an associate justice.

Thus, as Ella Wheeler Wilcox said, “no question is ever settled until it is settled right.” Yet, what is “right” increasingly appears like a simple question of math rather than principle in the United States Senate.

It is doubtful that Kavanaugh could be impeached absent clear proof of perjury before Congress. Thus, what happens next year may be less important than what happens this week. Senators on both sides must decide if they will act to further their constitutional institution or just their political instincts.

Reprinted with permission from JonathanTurley.org.