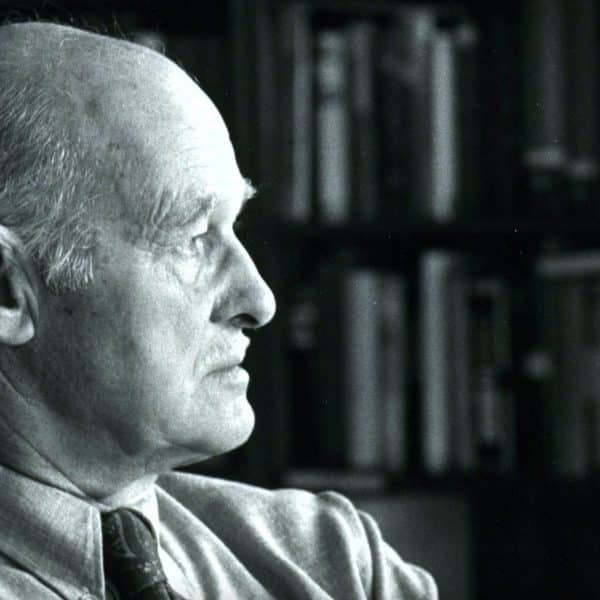

In 1997, veteran U.S. diplomat George Kennan stated that ‘expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American foreign policy in the entire post-Cold War era’. Twenty-eight years later, who would say he was wrong?

George Kennan famously authored the U.S. policy of containment of the Soviet Union, in an article in the New York Times of 1947, which he signed X, to maintain his anonymity. His view was that containment would lead to the eventual break up or mellowing of Soviet power and, as it turns out, the former prediction came to pass.

Yet, he was opposed to the expansion of NATO after the collapse of the Soviet Union and argued that asking European nations to choose between NATO and Russia would eventually lead to conflict.

In an article in the New York Times of 5 February 1997 he asked: ‘Why, with all the hopeful possibilities engendered by the end of the cold war, should East-West relations become centred on the question of who would be allied with whom and, by implication, against whom in some fanciful, totally unforeseeable and most improbable future military conflict?’

His article was intended to influence discussions ahead of the July 1997 NATO Summit in Madrid which would consider the planned expansion of NATO to include the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. Each state had suffered under Soviet repression after World War II but were now free and democratic after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact.

Kennan’s warning went unheeded, the NATO Summit agreed to the inclusion of three of the four former Warsaw Pact countries within NATO, excluding Slovakia which had not received the required number of votes in a referendum.

On 1 May 1998, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution approving expansion, as every NATO member state is required to do. After the Senate Resolution, then President Clinton said at the White House, ”by admitting Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic, we come even closer than ever to realizing a dream of a generation – a Europe that is united, democratic and secure for the first time since the rise of nation-states on the European continent.’

The idea then, which continues today, is that NATO is a military alliance of countries with the same democratic principles acting as a bulwark against military aggression, by implication, from Russia. Yet, Kennan seemed to consider absurd the idea – which peppers political and media discourse still today – that Russia aspires to conquer western Europe by military means.

In a separate New York Times article on 2 May 1998, the day after the U.S. Senate resolution, Kennan said, ‘I was particularly bothered by the references to Russia as a country dying to attack Western Europe. Don’t people understand? Our differences in the cold war were with the Soviet Communist regime. And now we are turning our backs on the very people who mounted the greatest bloodless revolution in history to remove that Soviet regime.’

In his 1997 article, Kennan went on to say that Russia would ‘have no choice but to accept [NATO] expansion as a military fait accompli. But they would continue to regard it as a rebuff by the West and would likely look elsewhere for guarantees of a secure and hopeful future for themselves.’

Russia did accept the expansion of NATO as a fait accompli, in part because she was too weak to resist. In 1998, the Russian Federation was possibly at its lowest point after the collapse of the Soviet Union. On 17 August 1998, Russia defaulted on its sovereign debt and devalued the rouble. In visibly declining health, President Yeltsin cut an increasingly weak and erratic figure on the world stage. The billionaire oligarch class had built an outsized role in Russian politics, having swept up state assets under the Loans for Shares scheme, and having bankrolled Yeltsin’s 1996 election success, for their own personal gain. Russia was politically, economically and militarily weak, and internally distracted by a costly war in Chechnya. It was by no measure comparable to the fearsome might of the Soviet Union, or a threat to NATO. Indeed, tentatively, and in ways that were sometimes strained, Russia and NATO ended up collaborating, including in Kosovo in 1999.

The next crunch point came after the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington DC on 11 September 2001.

President Putin was one of the first world leaders to phone President Bush to express his condolences to the president and to the American people and offer his unequivocal support for whatever reactions the American president might decide to take. This led quite quickly to a period of U.S.-Russia cooperation, including concrete Russian assistance to the U.S. campaign in Afghanistan and acquiescence to the establishment of U.S. bases in Central Asia.

Michael McFaul, who is now one of the most vocal anti-Russia hawks, wrote an article for the Carnegie Endowment, saying that ‘the potential to build a new foundation for Russia-American relations is great.’ He advanced a radical agenda, starting with a declaration that ‘the United States no longer recognizes Russia as the successor state to the Soviet Union.’ In substantive terms, this meant a repudiation of the idea that Russia represented a threat to NATO in the way that the Soviet Union had.

McFaul proposed deeper Russia-NATO collaboration and possible future Russian membership, which President Putin had shown a willingness to consider. He also recommended other measures, including removing Soviet era trade restrictions, lifting a ban on NATO countries buying Russian weapons and encouraging a closer relationship between Russia and the EU.

However, one week after McFaul’s article, the Brookings Institution wrote an article, raising a red flag against any departure from U.S. engagement on across the globe as a concession to the new ‘war on terror.’ Among other things, it pointed out that ‘the new premium on Russian cooperation.. might make it harder or more costly for Washington to proceed with current policy plans to withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty, enlarge NATO, or press for human rights in Chechnya.

Deepening Russian-American collaboration immediately ran up against the separate juggernaut of NATO expansion which had continued to gather pace after the 1998. Nine other former Soviet or Warsaw Pact countries were already waiting in the wings to join NATO, and a comprehensive reboot of relations with Russia would have made expansion more difficult. In the teeth of Russian concern about the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, and western concern about President Putin’s clampdown on the oligarchs, U.S.-Russia collaboration lost steam and NATO pressed on regardless. Seven new Members joined the military alliance in 2004, including the Baltic States, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia, bringing NATO much closer to Russia’s border.

In his 5 February 1997 article, Kennan said that NATO expansion ‘may be expected to inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies in Russian opinion; to have an adverse effect on the development of Russian democracy; to restore the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations, and to impel Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to our liking.’

Ten years later, on 10 February 2007, President Putin made his now famous speech at the Munich Security Conference, in which he said, ‘I think it is obvious that NATO expansion does not have any relation with the modernisation of the Alliance itself or with ensuring security in Europe. On the contrary, it represents a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust. And we have the right to ask: against whom is this expansion intended?’

The following year at the 2008 NATO Bucharest summit, nonetheless advanced the idea of Georgia and Ukraine joining NATO one day. President Putin, who joined part of the Summit, conceded in his speech that he could not veto NATO expansion. But he went on to asset that ‘if we introduce [Ukraine] into NATO.. it may put the state on the verge of its existence. Complicated internal political problems are taking place there. We should act.. very-very carefully.’

His views were again ignored, and the idea of Georgian and Ukrainian membership of NATO was set in train with the consequences that we see today.

However, a central truth of NATO expansion towards Ukraine, visible to me in 2013 when I first started to focus on Russia, is that western powers have never committed to fighting for Ukraine’s right to join. This is exactly the point that George Kennan acknowledge in his 1998 comments. He said, ‘we have signed up to protect a whole series of countries, even though we have neither the resources nor the intention to do so in any serious way.’

Looking at Ukraine today, with its de facto exclusion from NATO membership, denied the deployment of U.S. military force to support for its war effort and practically bankrupt from the slow depletion of western financial support, who would say that Kennan was wrong, 28 years ago?

The 1998 New York Times article in which Kennan was widely quoted also noted that ‘future historians will surely remark upon the utter poverty of imagination that characterized U.S. foreign policy in the late 1990’s’. History would surely judge western foreign policy since 2013 more harshly still.

Reprinted with permission from Strategic Culture Foundation.