On 7 October 2022, late in the evening, at around 11.30 pm, I was detained at Gatwick Airport in London by anti-terrorism police. I was not released until shortly before 1 am and my computer was taken from me. It has not yet been returned.

My passport and all my personal belongings – my wallet, my phone, my keys, everything – were removed. I was taken to a room where I was questioned for an hour by two anti-terrorism police officers, acting under powers given to the police (as I learned for the first time) by Schedule 3 of the 2019 Counter-terrorism and Border Security Act.

The Act is supposedly designed to allow the police to detain ‘hostile actors’ who are travelling to the country to ‘plan, prepare or carry out their hostile acts’ (according to the leaflet the officers gave me). But the Act itself says, ‘An examining officer may exercise the powers under this paragraph whether or not there are grounds for suspecting that a person is or has been engaged in hostile activity’ (my emphasis)[1]. So an Act ostensibly designed to allow hostile actors to be stopped in fact applies indiscriminately to everyone, according to its own explicit terms.

It is certainly surprising that the powers were wielded, in my case, against a British national. Nationals should not normally be questioned in this way about their reasons for entering the territory of their own country.

One of the officers opened the interrogation by saying that I was not being detained and that therefore I could not have access to a lawyer. But of course I was being detained, since it was impossible for me to leave the interrogation room and, even more so, the airport, without my passport and personal effects. (I was kept on the ‘air side’, i.e. before passing through passport control.) The word ‘detained’ has evidently been emptied of all meaning.

According to the leaflet, ‘Unlike most other Police powers, the power to stop, question, search and, if necessary, detain persons under Schedule 3 does not require authority or any suspicion.’ So the special powers enjoyed by the Police at UK ports are a ‘regime of exception’ in which the normal safeguards of the rule of law have been tossed aside.

It goes on, ’You can be searched, and anything you have with you … this includes electronic devices … where searches are conducted, there is no requirement for a written notice of search to be provided to you. Under certain circumstances, the officer can seize any property they find.’

What are these ‘certain circumstances’? When I protested at the fact that my computer was being taken from me, which would prevent me from working until it is returned, and when I offered to bring it to a police station the following day, the officer replied that it was out of the question that it would not be taken. In other words, there are no ‘certain circumstances.’ The seizure of such devices is, on the contrary, the rule.

In a state of law, the Police can search someone’s property only with a search warrant. This is a document signed by a judge which authorises private property to be searched and seized. If you look up ‘search warrant’ in Wikipedia, it says, ‘In certain authoritarian nations, police officers may be allowed to search individuals and property without having to obtain court permission or provide justification for their actions.’ According to this standard, the UK is now an ‘authoritarian nation.’

It is precisely what separates a legal state from a dictatorship that the work of the police is not abused for political purposes, yet this is what occurred to me.

The officers questioned me about my work at the Institute of Democracy and Cooperation in Paris from 2008 to 2018 and about my work at the European Parliament since then, and more recently for FVD. All the information they wanted is available publicly, for instance on Wikipedia. The questioning was polite but amateurish.

I was asked about my political views. The officer said, ‘It is a free country, not everyone is so lucky.’ I believe this is what is called ‘the British sense of humour’.

The officers told me that they had had two or three hours to prepare. This means that they were alerted in London to my imminent arrival at the moment when my boarding pass was scanned in Budapest. Everyone should know this.

They spent those hours looking things up on the Internet. The officer questioning me seemed unsure of what he was really trying to find out. The Internet, as everyone should know, is a veritable cesspit of false information and there are endless claims on it about me which are untrue. Many of these have been repeated recently in the Dutch press, as journalists go online, find what they are looking for and repeat lies told earlier by others. In my case, they never tire of telling the same fairy tale.

It is bad enough when journalists do this but it is frightening to think that anti-terrorism police officers regard Google as a reliable source of information. One dreads to think how many genuinely hostile actors pass through the net if this is the Police’s idea of investigation. Unfortunately that is the state of the world today.

It is particularly symbolic that this should happen to me. Ever since I started to get interested in international criminal law over 20 years ago, I have criticised the way in which international tribunals toss aside the myriad rules and procedures which have accumulated over the centuries to ensure due process. The British are traditionally proud of these procedures which have protected citizens against abusive state power for centuries. I have repeatedly warned that these dictatorial practices would soon percolate down into national jurisdictions and destroy the precious inheritance known as the rule of law. This has now happened.

Ever since the EU announced its Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime in December 2020, moreover, I have also pointed out that the EU has given itself the power to punish individuals by executive order. This is a very dangerous development. Individuals are punished under this regime without any legal procedure (no trial) and without any means of defending themselves. So much for human rights! I have warned for two years now that citizens of Western states would themselves be the target of these sanctions. This duly happened in July when a British blogger, Graham Philipps, was sanctioned by the United Kingdom which has the same system as the EU and the US.

In other words I, who have been warning that these procedures, introduced at international level, would soon corrupt the criminal law in domestic jurisdictions, have now been proved horribly right by an example of this abuse of which I have now personally been a victim. It was a profoundly disturbing experience.

Shortly before it happened, FVD International tweeted its disapproval of the EU sanctions imposed on the philosopher, Alexander Dugin. As we showed with a screen shot of the relevant EU document, the European Council (i.e. the executive) sanctioned Dugin purely for his views. Nowhere it is alleged that he has actually participated in the invasion of Ukraine nor even that he is guilty of incitement. Instead, he is sanctioned for thoughtcrime.

Some people who do not like Dugin are pleased at this. But they should understand that these are seriously abusive powers which can easily, as in my case, be directed against totally innocent people. To such people I can find no better response that the famous remarks by Pastor Martin Niemöller:

[1] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2019/3/schedule/3

Reprinted with author’s permission from Forum for Democracy.

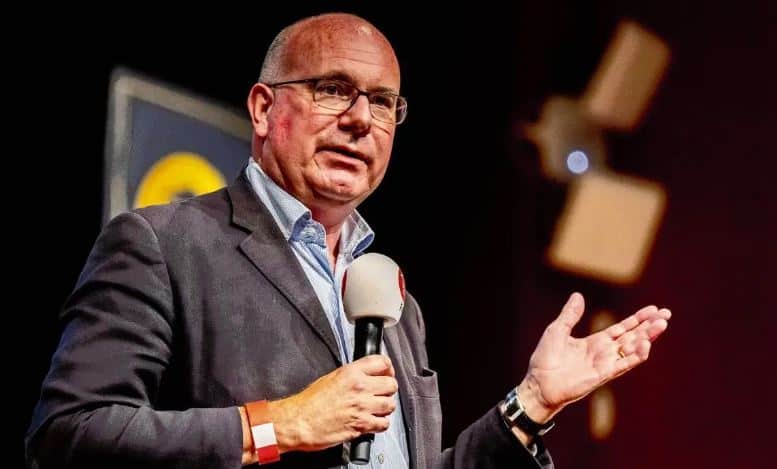

John Laughland is Director of Forum for Democracy International and a Member of the Academic Board of the Ron Paul Institute. He is a Visiting Fellow at Mathias Corvinus College in Budapest, Hungary.