At a May press conference capping his tenure as special counsel, Robert Mueller emphasized what he called “the central allegation” of the two-year Russia probe. The Russian government, Mueller sternly declared, engaged in “multiple, systematic efforts to interfere in our election, and that allegation deserves the attention of every American.” Mueller’s comments echoed a January 2017 Intelligence Community Assessment (ICA) asserting with “high confidence” that Russia conducted a sweeping 2016 election influence campaign. “I don’t think we’ve ever encountered a more aggressive or direct campaign to interfere in our election process,” then-Director of National Intelligence James Clapper told a Senate hearing.

While the 448-page Mueller report found no conspiracy between Donald Trump’s campaign and Russia, it offered voluminous details to support the sweeping conclusion that the Kremlin worked to secure Trump’s victory. The report claims that the interference operation occurred “principally” on two fronts: Russian military intelligence officers hacked and leaked embarrassing Democratic Party documents, and a government-linked troll farm orchestrated a sophisticated and far-reaching social media campaign that denigrated Hillary Clinton and promoted Trump.

But a close examination of the report shows that none of those headline assertions are supported by the report’s evidence or other publicly available sources. They are further undercut by investigative shortcomings and the conflicts of interest of key players involved:

None of this means that the Mueller report’s core finding of “sweeping and systematic” Russian government election interference is necessarily false. But his report does not present sufficient evidence to substantiate it. This shortcoming has gone overlooked in the partisan battle over two more highly charged aspects of Mueller’s report: potential Trump-Russia collusion and Trump’s potential obstruction of the resulting investigation. As Mueller prepares to testify before House committees later this month, the questions surrounding his claims of a far-reaching Russian influence campaign are no less important. They raise doubts about the genesis and perpetuation of Russiagate and the performance of those tasked with investigating it.

Uncertainty Over Who Stole the Emails

The Mueller report’s narrative of Russian hacking and leaking was initially laid out in a July 2018 indictment of 12 Russian intelligence officers and is detailed further in the report. According to Mueller, operatives at Russia’s main intelligence agency, the GRU, broke into Clinton campaign Chairman John Podesta’s emails in March 2016. The hackers infiltrated Podesta’s account with a common tactic called spear-phishing, duping him with a phony security alert that led him to enter his password. The GRU then used stolen Democratic Party credentials to hack into the DNC and Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) servers beginning in April 2016. Beginning in June 2016, the report claims, the GRU created two online personas, “DCLeaks” and “Guccifer 2.0,” to begin releasing the stolen material. After making contact later that month, Guccifer 2.0 apparently transferred the DNC emails to the whistleblowing, anti-secrecy publisher WikiLeaks, which released the first batch on July 22 ahead of the Democratic National Convention.

The report presents this narrative with remarkable specificity: It describes in detail how GRU officers installed malware, leased US-based computers, and used cryptocurrencies to carry out their hacking operation. The intelligence that caught the GRU hackers is portrayed as so invasive and precise that it even captured the keystrokes of individual Russian officers, including their use of search engines.

In fact, the report contains crucial gaps in the evidence that might support that authoritative account. Here is how it describes the core crime under investigation, the alleged GRU theft of DNC emails:

Between approximately May 25, 2016 and June 1, 2016, GRU officers accessed the DNC’s mail server from a GRU-controlled computer leased inside the United States. During these connections, Unit 26165 officers appear to have stolen thousands of emails and attachments, which were later released by WikiLeaks in July 2016. [Italics added for emphasis.]

The report’s use of that one word, “appear,” undercuts its suggestions that Mueller possesses convincing evidence that GRU officers stole “thousands of emails and attachments” from DNC servers. It is a departure from the language used in his July 2018 indictment, which contained no such qualifier:

“It’s certainly curious as to why this discrepancy exists between the language of Mueller’s indictment and the extra wiggle room inserted into his report a year later,” says former FBI Special Agent Coleen Rowley. “It may be an example of this and other existing gaps that are inherent with the use of circumstantial information. With Mueller’s exercise of quite unprecedented (but politically expedient) extraterritorial jurisdiction to indict foreign intelligence operatives who were never expected to contest his conclusory assertions in court, he didn’t have to worry about precision. I would guess, however, that even though NSA may be able to track some hacking operations, it would be inherently difficult, if not impossible, to connect specific individuals to the computer transfer operations in question.”

The report also concedes that Mueller’s team did not determine another critical component of the crime it alleges: how the stolen Democratic material was transferred to WikiLeaks. The July 2018 indictment of GRU officers suggested – without stating outright – that WikiLeaks published the Democratic Party emails after receiving them from Guccifer 2.0 in a file named “wk dnc linkI .txt.gpg” on or around July 14, 2016. But now the report acknowledges that Mueller has not actually established how WikiLeaks acquired the stolen information: “The Office cannot rule out that stolen documents were transferred to WikiLeaks through intermediaries who visited during the summer of 2016.”

Another partially redacted passage also suggests that Mueller cannot trace exactly how WikiLeaks received the stolen emails. Given how the sentence is formulated, the redacted portion could reflect Mueller’s uncertainty:

Contrary to Mueller’s sweeping conclusions, the report itself is, at best, suggesting that the GRU, via its purported cutout Guccifer 2.0, may have transferred the stolen emails to WikiLeaks.

A Questionable Timeline

Mueller’s uncertainty over the theft and transfer of Democratic Party emails isn’t the only gap in his case. Another is his timeline of events – a critical component of any criminal investigation. The report’s timeline defies logic: According to its account, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange announced the publication of the emails not only before he received the documents, but before he even communicated with the source that provided them.

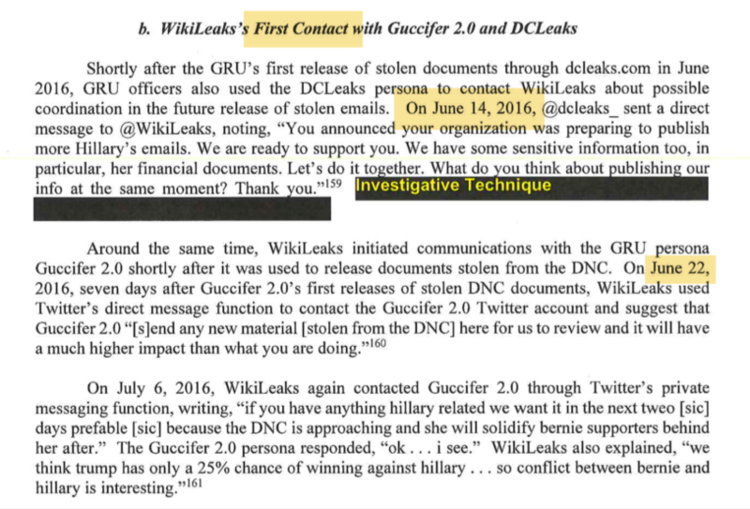

As the Mueller report confirms, on June 12, 2016, Assange told an interviewer, “We have upcoming leaks in relation to Hillary Clinton, which is great.” But Mueller reports that “WikiLeaks’s First Contact With Guccifer 2.0 and DC Leaks” comes two days after that announcement:

If Assange’s “First Contact” with DC Leaks came on June 14, and with Guccifer 2.0 on June 22, then what was Assange talking about on June 12? It is possible that Assange heard from another supposed Russian source before then; but if so, Mueller doesn’t know it. Instead the report offers the implausible scenario that their first contact came after Assange’s announcement.

There is another issue with the report’s Guccifer 2.0-WikiLeaks timeline. Assange would have been announcing the pending release of stolen emails not just before he heard from the source, but also before he received the stolen emails. As noted earlier, Mueller suggested that WikiLeaks received the stolen material from Guccifer 2.0 “on or around” July 14 – a full month after Assange publicly announced that he had them.

In yet one more significant inconsistency, Mueller asserts that the two Russian outfits running the Kremlin-backed operation — Guccifer 2.0 and DC Leaks – communicated about their covert activities over Twitter. Mueller reports that on Sept. 15, 2016:

The Twitter account@guccifer_2 sent @dcleaks_ a direct message, which is the first known contact between the personas. During subsequent communications, the Guccifer 2.0 persona informed DCLeaks that WikiLeaks was trying to contact DCLeaks and arrange for a way to speak through encrypted emails.

Why would Russian intelligence cutouts running a sophisticated interference campaign communicate over an easily monitored social media platform? In one of many such instances throughout the report, Mueller shows no curiosity in pursuing this obvious question.

For his part, Assange has repeatedly claimed that Russia was not his source and that the US government does not know who was. “The US intelligence community is not aware of when WikiLeaks obtained its material or when the sequencing of our material was done or how we obtained our material directly,” Assange said in January 2017. “WikiLeaks sources in relation to the Podesta emails and the DNC leak are not members of any government. They are not state parties. They do not come from the Russian government.”

Guccifer 2.0: A Sketchy Source

While Mueller admits he does not know for certain how the DNC emails were stolen or how they were transmitted to WikiLeaks, the report creates the impression that Russian intelligence cutout Guccifer 2.0 supplied the stolen material to Assange.

In fact, there are strong grounds for doubt. To begin with, Guccifer 2.0 – who was unknown until June 2016 – burst onto the scene to demand credit as WikiLeaks’ source. This publicity-seeking is not standard spycraft.

More important, as Raffi Khatchadourian has reported for The New Yorker, the documents Guccifer 2.0 released directly were nowhere near the quality of the material published by WikiLeaks. For example, on June 18, Guccifer 2.0 released documents that it claimed were from the DNC, “but which were almost surely not,” Khatchadourian notes. Neither was the material Guccifer 2.0 teased as a “dossier on Hillary Clinton from DNC.” The material Guccifer 2.0 initially promoted in June also contained easily discoverable Russian metadata. The computer that created it was configured for the Russian language, and the username was “Felix Dzerzhinsky,” the Bolshevik-era founder of the first Soviet secret police.

WikiLeaks only made contact with Guccifer 2.0 after the latter publicly invited journalists “to send me their questions via Twitter Direct Messages.” And, more problematic given the central role the report assigned to Guccifer 2.0, there is no direct evidence that WikiLeaks actually released anything that Guccifer 2.0 provided. In a 2017 interview, Assange said he “didn’t publish” any material from that source because much of it had been published elsewhere and because “we didn’t have the resources to independently verify.”

Mueller Didn’t Speak With Assange

Some of these issues might have been resolved had Mueller not declined to interview Assange, despite Assange’s multiple efforts.

According to a 2018 report by John Solomon in The Hill, Assange told the Justice Department the previous year that he “was willing to discuss technical evidence ruling out certain parties” in the leaking of Democratic Party emails to WikiLeaks. Given Assange’s previous denials of Russia’s involvement, that seems to indicate he was willing to provide evidence that Moscow was not his source. But he never got the chance. According to Solomon, FBI Director James Comey personally intervened with an order that US officials “stand down,” setting off a chain of events that scuttled the talks.

Assange also made public offers to testify before Congress. The Mueller report makes no mention of these overtures, though it does cite and dismiss “media reports” that “Assange told a US congressman that the DNC hack was an ‘inside job,’ and purported to have ‘physical proof’ that Russians did not give materials to Assange.”

Mueller does not explain why he included Assange’s comments as reported by media outlets in his report but decided not to speak with Assange directly, or ask to see his “physical proof,” during a two-year investigation.

No Server Inspection, Reliance on CrowdStrike

Before he nixed US government contacts with Assange, Comey was implicated in another key investigative lapse – the FBI’s failure to conduct its own investigation of the DNC’s servers, which housed the record of alleged intrusions and malware used to steal information. As Comey told Congress in March 2017, the FBI “never got direct access to the machines themselves.” Instead, he explained, the bureau relied on CrowdStrike, a cybersecurity firm hired by the DNC, which “shared with us their forensics from their review of the system.”

While acknowledging that the FBI would “always prefer to have access hands-on ourselves, if that’s possible,” Comey emphasized his confidence in the information provided by CrowdStrike, which he called “a highly respected private company” and “a high-class entity.”

CrowdStrike’s accuracy is far from a given. Days after Comey’s testimony, CrowdStrike was forced to retract its claim that Russian software was used to hack Ukrainian military hardware. CrowdStrike’s error is especially relevant because it had accused the GRU of using that same software in hacking the DNC.

There is also reason to question CrowdStrike’s impartiality. Its co-founder, Dmitri Alperovitch, is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, the preeminent Washington think tank that aggressively promotes a hawkish posture towards Russia. CrowdStrike executive Shawn Henry, who led the forensics team that ultimately blamed Russia for the DNC breach, previously served as assistant director at the FBI under Mueller.

And CrowdStrike was hired to perform the analysis of the DNC servers by Perkins Coie – the law firm that also was responsible for contracting Fusion GPS, the Washington, D.C.-based opposition research firm that produced the now discredited Steele dossier alleging salacious misconduct by Trump in Russia and his susceptibility to blackmail.

A CrowdStrike spokesperson declined a request for comment on its role in the Russia investigation.

The picture is further clouded by the conflicting accounts regarding the servers. A DNC spokesperson told BuzzFeed in early January 2017 that “the FBI never requested access to the DNC’s computer servers.” But Comey told the Senate Select Intelligence Committee days later that the FBI made “multiple requests at different levels,” but for unknown reasons, he explained, those requests were denied.

While failing to identify the “different levels” he consulted, Comey never explained why the FBI took no for an answer. As part of a criminal investigation, the FBI could have seized the servers to ensure a proper chain of evidentiary custody. In investigating a crime, alleged victims do not get to dictate to law enforcement how they can inspect the crime scene.

The report fails to address any of this, suggesting a lack of interest in even fundamental questions if they might reflect poorly on the FBI.

The Mueller report states that “as part of its investigation, the FBI later received images of DNC servers and copies of relevant traffic logs.” But it does not specify how much “later” it received those server images or who provided them. Based on the statements of Comey and other US officials, it is quite likely that they came from CrowdStrike, though the company gets only passing mention in the redacted report.

Asked for comment, Special Counsel spokesman Peter Carr declined to answer whether the Mueller team relied on CrowdStrike for its allegations against the GRU. Carr referred queries to the Justice Department’s National Security Division, which declined to comment, and to the US Western District of Pennsylvania, which did not respond.

If CrowdStrike’s role in the investigation raises a red flag, the potential exclusion of another entity raises an equally glaring one. According to former NSA Technical Director Bill Binney, the NSA is the only US agency that could conclusively determine the source of the alleged DNC email hacks. “If this was really an internet hack, the NSA could easily tell us when the information was taken and the route it took after being removed from the [DNC] server,” Binney says. But given Mueller’s qualified language and his repeated use of “in or around” rather than outlining specific, down-to-the-second timestamps – which the NSA could provide — Binney is skeptical that NSA intelligence was included in the GRU indictment and the report.

There has been no public confirmation that intelligence acquired by the NSA was used in the Mueller probe. Asked whether any of its information had been used in the allegations against the GRU, or had been declassified for public release in Mueller’s investigation, a spokesperson for the National Security Agency declined to comment.

Redacted CrowdStrike Reports

While the extent of the FBI’s reliance on CrowdStrike remains unclear, critical details are beginning to emerge via an unlikely source: the legal case of Roger Stone – the Trump adviser Mueller indicted for, among other things, allegedly lying to Congress about his failed efforts to learn about WikiLeaks’ plans regarding Clinton’s emails.

Lawyers for Stone discovered that CrowdStrike submitted three forensic reports to the FBI that were redacted and in draft form. When Stone asked to see CrowdStrike’s un-redacted versions, prosecutors made the explosive admission that the US government does not have them. “The government … does not possess the information the defendant seeks,” prosecutor Jessie Liu wrote. This is because, Liu explained, CrowdStrike itself redacted the reports that it provided to the government:

At the direction of the DNC and DCCC’s legal counsel, CrowdStrike prepared three draft reports. Copies of these reports were subsequently produced voluntarily to the government by counsel for the DNC and DCCC. At the time of the voluntary production, counsel for the DNC told the government that the redacted material concerned steps taken to remediate the attack and to harden the DNC and DCCC systems against future attack. According to counsel, no redacted information concerned the attribution of the attack to Russian actors.

In other words, the government allowed CrowdStrike and the Democratic Party’s legal counsel to decide what it could and could not see in reports on Russian hacking, thereby surrendering the ability to independently vet their claims. The government also took CrowdStrike’s word that “no redacted information concerned the attribution of the attack to Russian actors.”

According to an affidavit filed for Stone’s defense by Binney, the speed transfer rate and the file formatting of the DNC data indicate that they were moved on to a storage device, not hacked over the Internet. In a rebuttal, Stone’s prosecutors said that the file information flagged by Binney “would be equally consistent with Russia intelligence officers using a thumb drive to transfer hacked materials among themselves after the hack took place.” In an interview with RealClearInvestigations, Binney could not rule out that possibility. But conversely, the evidence laid out by Mueller is so incomplete and uncertain that Binney’s theory cannot be ruled out either. The very fact that DoJ prosecutors, in their response to Binney, do not rule out his theory that a thumb drive was used to transfer the material is an acknowledgment in that direction.

The lack of clarity around Mueller’s intelligence community sourcing might appear inconsequential given the level of detail in his account of alleged Russian hacking. But in light of the presence of potentially biased and politically conflicted sources like CrowdStrike, and the absence of certainty revealed in Mueller’s lengthy account, the fact that his sourcing remains an open question makes it difficult to accept that he has delivered definitive answers. If Mueller had the invasive window into Russian intelligence that he claims to, it seems incongruous that he would temper his purported descriptions of their actions with tentative, qualified language. Mueller’s hedging suggests a broader conclusion at odds with the report’s own findings: that the US government does not have ironclad proof about who hacked the DNC.

Social Media Campaign

Mueller’s other “central allegation” regards a “Russian ‘Active Measures’ Social Media Campaign” with the aim of “sowing discord” and helping to elect Trump.

In fact, Mueller does not directly attribute that campaign to the Russian government, and makes only the barest attempt to imply a Kremlin connection. According to Mueller, the social media “form of Russian election influence came principally from the Internet Research Agency, LLC (IRA), a Russian organization funded by Yevgeniy Viktorovich Prigozhin and companies he controlled.”

After two years and $35 million, Mueller apparently failed to uncover any direct evidence linking the Prigozhin-controlled IRA’s activities to the Kremlin. His best evidence is that “[n]umerous media sources have reported on Prigozhin’s ties to Putin, and the two have appeared together in public photographs.” The footnote for this references a lone article in the New York Times. (Both the Times and the Washington Post are cited frequently throughout the report. The two outlets received and published intelligence community leaks throughout the Russia probe.)

Even putting aside the complete absence of the Kremlin, the case that the Russian government sought to influence the US election via a social media campaign is hard to grasp given how minuscule it was. Mueller says the IRA spent $100,000 between 2015 and 2017. Of that, just $46,000 was spent on Russian-linked Facebook ads before the 2016 election. That amounts to about 0.05% of the $81 million spent on Facebook ads by the Clinton and Trump campaigns combined — which is itself a tiny fraction of the estimated $2 billion spent by the candidates and their supporting PACS.

Then there is the fact that so little of this supposed election interference campaign content actually concerned the election. Mueller himself cites a review by Twitter of tweets from “accounts associated with the IRA” in the 10 weeks before the 2016 election, which found that “approximately 8.4%… were election-related.” This tracks with a report commissioned by the US Senate that found that “explicitly political content was a small percentage” of the content attributed to the IRA. The IRA’s posts “were minimally about the candidates,” with “roughly 6% of tweets, 18% of Instagram posts, and 7% of Facebook posts” having “mentioned Trump or Clinton by name.”

Yet Mueller circumvents this with what sound like impressive figures:

IRA-controlled Twitter accounts separately had tens of thousands of followers, including multiple US political figures who retweeted IRA-created content. In November 2017, a Facebook representative testified that Facebook had identified 470 IRA-controlled Facebook accounts that collectively made 80,000 posts between January 2015 and August 2017. Facebook estimated the IRA reached as many as 126 million persons through its Facebook accounts. In January 2018, Twitter announced that it had identified 3,814 IRA-controlled Twitter accounts and notified approximately 1.4 million people Twitter believed may have been in contact with an IRA-controlled account.

Upon scrutiny, Mueller’s figures are exaggerated, to say the least. Take Mueller’s claim that Russian posts reached “as many as 126 million” Facebook users. That figure is in fact a spin on Facebook’s own guess, as articulated by Facebook general counsel Colin Stretch’s congressional testimony in October 2017. “Our best estimate,” Stretch told lawmakers, “is that approximately 126 million people may have been served content from a page associated with the IRA at some point during the two-year period.” And the “two-year period” extends far beyond the 2016 election, to August 2017. Overall, Stretch added, posts from suspected Russian accounts showing up in Facebook’s News Feed comprised “approximately 1 out of [every] 23,000 pieces of content.”

Yet another reason to question the Russian operation’s sophistication is the quality of its content. The IRA’s most shared pre-election Facebook post was a cartoon of a gun-wielding Yosemite Sam. On Instagram, the best-received image urged users to give it a “Like” if they believe in Jesus. The top IRA post on Facebook before the election that mentioned Hillary Clinton was a conspiratorial screed about voter fraud. Another ad featured Jesus consoling a dejected young man by telling him: “Struggling with the addiction to masturbation? Reach out to me and we will beat it together.”

Mueller also reports that the IRA successfully organized “dozens” of rallies “while posing as US grassroots activists.” Sounds impressive, but the most successful effort appears to have been in Houston, where Russian trolls allegedly organized dueling rallies pitting a dozen white supremacists against several dozen counter-protesters outside an Islamic center. Elsewhere, the IRA had underwhelming results, according to media reports: At several rallies in Florida “it’s unclear if anyone attended,” the Daily Beast later noted; “no people showed up to at least one,” and “ragtag groups” showed up at others, the Washington Post reported, including one where video footage captured a crowd of eight people.

Far from exposing a sophisticated propaganda campaign, the reports suggest that Russian troll farm workers engaged in futile efforts to spark contentious rallies in a handful of states. When it comes to the ads, they may have been engaging in clickbait capitalism: targeting unique demographics like African Americans or evangelicals in a bid to attract large audiences for commercial purposes. Reporters who have profiled the IRA have commonly described it as “a social media marketing campaign.” Mueller’s February 2018 indictment of the IRA disclosed that it sold “promotions and advertisements” on its pages that generally sold in the $25-$50 range. “This strategy,” a Senate report from Oxford University’s Computational Propaganda Project observes, “is not an invention for politics and foreign intrigue, it is consistent with techniques used in digital marketing.”

That, in fact, was Facebook’s initial conclusion. As the Washington Post first reported, Facebook’s initial review of Russian social media activity in late 2016 and early 2017 found that the troll farm’s pages “had clear financial motives, which suggested that they weren’t working for a foreign government.” That view only changed, the Post added, after “aides to Hillary Clinton and Obama” developed “theories” to help them “explain what they saw as an unnatural turn of events” in their loss of the 2016 election. Among these theories: “Russian operatives who were directed by the Kremlin to support Trump may have taken advantage of Facebook and other social media platforms to direct their messages to American voters in key demographic areas.” Despite the fact that “these former advisers didn’t have hard evidence,” the Democratic aides found a receptive audience in both congressional intelligence committees. Democrat Mark Warner, the Senate intel vice chairman, personally flew out to Facebook headquarters in California to press the case. Not long after, in the summer of 2017, Facebook went public with its new “findings” about Russian trolls. Mueller has followed their lead – just as the FBI followed the leads of other Democratic sources in pursuing both the collusion (Fusion GPS) and Russian hacking (CrowdStrike) allegations.

John Brennan and the ICA

As it falls short of proving its case for a “sweeping and systematic” Russian interference campaign, the Mueller report also fails to support its claim regarding the motive behind such efforts. In the introduction to Volume I, Mueller states that “the investigation established that the Russian government perceived it would benefit from a Trump presidency and worked to secure that outcome.” But nowhere in the ensuing 440 pages does Mueller produce any evidence to substantiate that central claim.

Instead Mueller appears to be relying on the intelligence community assessment (ICA) released in January 2017 – four months before his appointment – that accused the Russian government of running an “influence campaign” that aimed “to undermine public faith in the US democratic process,” and hurt Hillary Clinton’s “electability and potential presidency” as part of what it called Russia’s “clear preference for President-elect Trump.”

But the ICA itself produced no evidence for any of these assertions. Its equivocation is even more blunt than Mueller’s: The ICA report’s conclusions, it states, are “not intended to imply that we have proof that shows something to be a fact.”

On the core conclusion that Russia aimed to help Trump, there is not even uniformity: While the FBI and CIA claim to have “high confidence” in that judgment, the NSA makes a conspicuous deviation in expressing that it has only “moderate confidence.”

As it casts doubt on a core allegation of Russia’s alleged motives, the NSA’s dissent debunks the oft-repeated claim that the ICA represented the consensus view of all 17 US intelligence agencies.

Moreover, it would even be misleading to portray the ICA as the product of the three agencies that produced it – the CIA, FBI, and NSA. Instead, there are multiple indications that the ICA is primarily the work of one person, who would spend the next two years accusing Trump of treason: then-CIA Director John Brennan.

A March 2018 report from Republicans on the House Intelligence Committee says that Brennan personally oversaw the entire ICA process from start to finish. In December 2016, the GOP report recounts, President Obama “directed … Brennan to conduct a review of all intelligence relating to Russian involvement in the 2016 elections.” The resulting ICA “was drafted by CIA analysts” and merely “coordinated with the NSA and the FBI.” The GOP report observes that Brennan’s CIA analysts were “subjected to an unusually constrained review and coordination process, which deviated from established CIA practice.”[Italics added for emphasis.] A lengthy Democratic rebuttal to the GOP members’ report does not refute any of these findings.

Echoing the NSA’s dissent, the House GOP questions the ICA’s conclusion that Putin interfered to secure Trump’s victory. The committee, they write, “identified significant intelligence tradecraft failings that undermine confidence in the ICA judgments regarding Russian President Vladimir Putin’s strategic objectives for disrupting the US election.” [Italics added for emphasis.]

The Brennan-run process may have also excluded dissenting views from other agencies. Jack Matlock, the former US Ambassador to Russia, has claimed that a “senior official” from the State Department’s intelligence wing, the Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR), informed him that it had reached a different conclusion about alleged Russian meddling, “but was not allowed to express it.” An INR spokesperson declined a request for comment.

The ICA’s production schedule also raises a red flag: The outgoing Obama administration tasked Brennan with churning it out in seemingly unprecedented time. “Ordinarily, the kind of assessment that you’re talking about, there would be something that would take well over a year to do, certainly many months to do,” former federal prosecutor Andrew McCarthy told the House Intelligence Committee in June. “…[S]eems to me, in this instance, there was a rush to get that out within a matter of days.”

But even if Brennan had been given all the time in the world, the very fact that he was placed in charge of the intelligence assessment was a massive conflict of interest. Brennan was handed the opportunity to validate, without independent scrutiny or oversight from unbiased sources, serious allegations that he himself helped generate.

Efforts to reach Brennan through MSNBC, where he is a commentator, were unsuccessful.

Months before he oversaw the intelligence assessment, Brennan played a critical role in the FBI’s decision to open the probe of Trump-Russia collusion. “I was aware of intelligence and information about contacts between Russian officials and US persons that raised concerns in my mind about whether or not those individuals were cooperating with the Russians, either in a witting or unwitting fashion,” Brennan told Congress in March 2017, “and it served as the basis for the FBI investigation to determine whether such collusion-cooperation occurred.”

On top of his self-described role in generating the investigation of possible Trump-Russia collusion, Brennan also played a critical role in generating the claim that the Russian government was waging an influence campaign. According to the book “The Apprentice” by the Washington Post’s Greg Miller, the CIA unit known as “Russia House” was “the point of origin” for the US intelligence community’s conclusion during the presidential campaign that “the Kremlin was actively seeking to elect Trump.” Brennan sequestered himself in his office to pore over the CIA’s material, “staying so late that the glow through his office windows remained visible deep into the night.” Brennan “ordered up,” not just vetted, “‘finished’ assessments – analytic reports that had gone through layers of review and revision,” Miller adds, but also “what agency veterans call the ‘raw stuff’ – the unprocessed underlying material.”

Anyone familiar with how cherry-picked, false intelligence made the case for the Iraq War will recognize “raw material” as a red flag. Here’s another: According to Miller, one piece of intelligence that was “a particular source of alarm to Brennan,” was the “bombshell” from “sourcing deep inside the Kremlin” that Putin himself had “authorized a covert operation” in order to, “in his own words … damage Clinton and help elect Trump” via “a cyber campaign to disrupt and discredit the US presidential race.” A former CIA operative described that sourcing as “the espionage equivalent of ‘the Holy Grail.'”

Undoubtedly, a mole within Putin’s inner circle – able to capture his exact orders – would indeed fit that description. But that raises the obvious question: If such a crown jewel of espionage exists, why would anyone in US intelligence allow it to be revealed? And why hadn’t that “Holy Grail” source been able to forewarn its American intelligence handlers of any number of Putin’s actions that have caught the US off-guard, from the annexation of Crimea to the Russian intervention in Syria?

Brennan was the first to alert President Obama of a Russian interference campaign, and subsequently oversaw the US intelligence response.

Since leaving office, Brennan has laid bare his personal animus towards Trump, going so far as to call him “treasonous” – an unprecedented charge for a former top intelligence official to make about a sitting president. In the weeks before Mueller issued his final report, Brennan was still predicting that members of Trump’s inner circle, including family members, would be indicted. Given Brennan’s bias and consistent patterns of errors, Mueller’s unquestioning, apparent reliance on a Brennan-run process is suspect.

Although Mueller seemed to accept the ICA’s explosive claims at face value, Brennan’s work product is now facing Justice Department scrutiny. The New York Times reported on June 12 that Attorney General William Barr is “interested in how the C.I.A. drew its conclusions about Russia’s election sabotage, particularly the judgment that Mr. Putin ordered that operatives help Mr. Trump.” In what is most likely a direct reference to Brennan, the Times adds that Barr “wants to know more about the C.I.A. sources who helped inform its understanding of the details of the Russian interference campaign,” as well as about “the intelligence that flowed from the C.I.A. to the F.B.I. in the summer of 2016.”

Until Barr completes his review of the Russia probe, the April 2018 report from GOP members of the House Intelligence Committee remains the only publicly available assessment of the Brennan-controlled ICA’s methodology. One reason for this is the fact that President Obama personally quashed a proposed bipartisan commission of inquiry into alleged Russian interference that would have inevitably subjected Brennan and other top intelligence officials to scrutiny. According to the Washington Post, in the aftermath of the November election, Obama administration officials discussed forming such a commission to conduct a sweeping probe of the alleged Russian interference effort and the US response. But after Obama’s then chief-of-staff, Denis McDonough, introduced the proposal, he:

began criticizing it, arguing that it would be perceived as partisan and almost certainly blocked by Congress. Obama then echoed McDonough’s critique, effectively killing any chance that a Russia commission would be formed.

With Obama having killed “any chance that a Russia commission would be formed,” there has been no thorough, independent oversight of the intelligence process that alleged an interference campaign by Russia and triggered an all-consuming investigation of the Trump campaign’s potential complicity.

New Opportunities to Answer Unresolved Questions

Barr’s ongoing review, and Mueller’s pending appearance before Congress, offer fresh opportunities to re-examine the affair’s fundamental inconsistencies. Authorized by the president to declassify documents, Barr could shed light on the role that CrowdStrike and other sources played in informing Mueller and the Brennan-directed ICA’s claims of a Russian interference campaign. When he appears before lawmakers, Mueller will likely face questions on other matters: from Democrats, his decision to punt on obstruction; from Republicans, his decision to carry out a prolonged investigation of Trump-Russia collusion despite likely knowing quite early on that there was no such case to make.

If the US government does not have a solid case to make against Russia, then the origins of Russiagate, and its subsequent predominance of US political and media focus, are potentially even more suspect. Given that allegation’s importance, and Mueller’s own uncertainty and inconsistencies, the special counsel and his aides deserve scrutiny for making a “central allegation” that they have yet to substantiate.

Correction:

July 5, 2019, 7:40 PM Eastern

An earlier version of this article misstated the month of FBI Director James Comey’s testimony in 2017 to Congress about the bureau’s handling of Democratic National Committee servers. It was in March, not January.

Reprinted with permission from Real Clear Investigations.