In recent years, the limits on America’s ability to shape important outcomes in the Middle East unilaterally—or even with a few European partners—have been dramatically underscored by strategically failed interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. Last year, President Obama’s inability to act on his declared intention to attack Syria after chemical weapons were used there in August made clear that Washington can no longer credibly threaten the effective use of force in the region. Still, American and other Western elites persist in thinking they can dictate the Middle East’s future by helping armed insurgents overthrow Syria’s recognized government. If Western powers don’t drop their insistence that President Bashar al-Assad leave power—even though he retains the support of a majority of Syrians and is winning his fight against opposition forces—and get serious about facilitating a political settlement between Assad and parts of the opposition, they will do further damage to their own already distressed position in the Middle East.

Since protests broke out in parts of Syria in March 2011, Western policy has focused on destabilizing President Assad and his government. American, British, and French decision-makers calculated that, by undermining Assad, they could inflict a damaging blow to Iran’s regional position. They also reckoned that targeting Assad would help coopt the Arab Awakening that had emerged in the months preceding the start of unrest in Syria. America and its British and French partners wanted to show that, after the loss of pro-Western regimes in Tunisia and Egypt and near misses in Bahrain and Yemen, it wasn’t just authoritarian regimes willing to subordinate their foreign policies to Washington that were at risk from popular discontent. Western powers wanted to demonstrate that it was also possible to challenge governments—like Assad’s—committed to foreign policy independence.

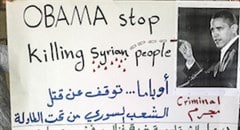

So, soon after unrest began in Syria, Washington and its European partners declared—as President Obama put it—that Assad “must go.” To this end, Western powers began goading an externally supported but internally conflicted “opposition” to mount an armed insurgency against Assad’s government.

Roots of Failure

Since the Cold War, pursuit of regime change by externally supported coups and insurgencies has come to seem an almost “normal” aspect of American foreign policy, used by U.S. administrations to eliminate governments seen as overly challenging to American ambitions or to deprive geopolitical rivals of allies. This approach, though, flies in the face of the most basic principles of international law and politics. What is the West’s moral high ground for preaching rule of law and observance of international norms when America and its partners regularly support the overthrow of recognized governments? (Vladimir Putin is not alone in noting Western hypocrisy on this point; for many Middle Easterners, Western encouragement of the overthrow of Ukraine’s elected government evokes U.S.-backed coups in their part of the world, from Iran in 1953 to Egypt last year.)

But, to paraphrase Talleyrand, Western strategy toward the Syrian conflict is worse than a crime; it’s a mistake. From the start, anyone prepared to look soberly at on-the-ground reality in Syria could see that arming a deeply divided opposition would not bring down Assad. All that outside support for armed oppositionists—a sizable percentage of whom are not even Syrian—has done is to take what began as indigenously generated protest over particular grievances and, from early on, turn it into a heavily militarized (and illegal) campaign against the recognized government of a United Nations member state. But the popular base for opposition to that government is too small to sustain a campaign that could actually bring it down—much less replace it with a functionally coherent order that Westerners could plausibly describe as “democracy.”

Since Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafiz, became Syria’s president in 1970, the main alternative to the Assads’ secular Ba’athism has been Sunni Islamism. For much of Hafiz’s thirty-year tenure, this was embodied in Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood, which—unlike the original Brothers in Egypt—conducted a violent, sustained, but ultimately unsuccessful revolt against the elder Assad. Since Bashar succeeded his father in 2000, the Islamist alternative has been embodied in more radical groups—some openly aligned to al-Qa’ida.

This is problematic for those who want to challenge the Assads. While a majority of Syrians are Sunni Arabs, those Syrians who don’t want to live in a Sunni Islamist state—including non-Islamist Sunnis along with Christians and non-Sunni Muslims—add up to more than half the population, providing the Assad government a strong base. Since early 2011, polling data, participation in the February 2012 referendum on a new constitution, participation in the May 2012 parliamentary elections, and other evidence indicate that at least half of Syrian society has continued to back Assad. There is no polling or other evidence indicating that anywhere close to a majority of Syrians wants Assad replaced by some part of the opposition. Indeed, NATO estimates that opposition support is declining as it becomes ever more sharply divided among secular liberals (mostly resident in London, Paris, and Washington, with little standing in Syria), Muslim Brotherhood-style Islamists (whose current standing in Syria is also questionable), and more radical, al-Qa’ida-like jihadis (the most effective opposition fighters).

The Rising Costs of Hubris

The West’s Syria strategy has backfired against virtually all the constituencies it was ostensibly intended to help. It has also backfired against Western interests.

Syria, of course, has paid the highest price of all, with over 130,000 killed (so far) and millions more displaced as a result of fighting between opposition elements and government forces. Iran—from the West’s perspective, the real target of the anti-Assad campaign—has had to bear the costs of stepped up support for the Syrian government. But the Western strategy of working with oppositionists to effect Assad’s downfall has not undermined Iran’s regional position. At the same time, the Syrian conflict is imposing increasingly serious security, economic, and political costs on Syria’s neighbors, especially Iraq, Lebanon, and Turkey—costs that, as they mount, could potentially threaten these countries’ long-term stability. More broadly, the conflict is helping to fuel a dangerous resurgence of sectarian tensions across the Middle East—in turn, giving new life to al-Qa’ida and similar jihadi movements around the region.

America and its British and French partners have not paid in blood or (much) treasure for their proxy intervention in Syria. They are, however, suffering various forms of self-inflicted damage to their own regional position—like the accelerating proliferation of violent jihadis.

It was utterly predictable that encouraging Saudi Arabia’s assumption of a leading role in funding and supplying Syrian oppositionists would condition the rise of violent, al-Qa’ida-like fighters to prominence in opposition ranks. America and its European allies have experience working with Saudi Arabia to fund jihadis willing to target a perceived common enemy. They tried it in Afghanistan and got al-Qa’ida and the Taliban as a result. They tried it in Libya and got a dead U.S. ambassador and three other murdered official Americans as a result. Yet Western powers opted to try this approach once again in Syria. And today, the U.S. Intelligence Community estimates that 26,000 “extremists” are now fighting in Syria—more than 7,000 of them brought in from outside the country. U.S. Director of National Intelligence James Clapper warns that many want not just to bring down the Assad government; they are preparing to attack Western interests—including the American homeland—directly.

Western powers are also paying for their ill-conceived Syria policy through increasing polarization of relations with Russia and China. Intelligence services for all five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council have identified Syrian-based jihadi extremism as a significant and growing security threat. The American, British, and French governments have only themselves to blame for this. The Russian and Chinese governments blame America, Britain, and France.

Strategically, the Syrian conflict has prompted closer Sino-Russian cooperation against Western efforts to usurp the Middle East’s balance of power by overthrowing independent regional governments. On March 17, 2011, the Security Council narrowly adopted a resolution authorizing use of force to protect civilian populations in Libya; Russia and China abstained, permitting the measure’s enactment. In short order, though, Washington and its partners distorted the resolution to turn civilian protection into a campaign of coercive regime change in Libya. Within weeks, Russian and Chinese officials were openly characterizing their acquiescence to the Libya resolution as a “mistake”—one they would not repeat on Syria. As early as June 2011, Moscow and Beijing indicated they were prepared to use their UN veto to block external intervention in Syria; they have done so three times already, and are ready to do so again, if necessary.

Western policy toward Syria has hardly persuaded Middle Eastern publics that the West actually supports their interest in political change. By backing Syrian oppositionists and calling for Assad to go, America and its European partners hoped to show that, somewhere in the Middle East, they could put themselves on the “right” side of history. But the hard truth—which Western posturing on Syria can’t obscure—is that demands by Arab publics for leaderships accountable to them, not to Washington and its allies, directly threaten the West’s longstanding strategy of securing regional dominance by partnering with local autocrats. (For the West, the problem with Assad isn’t that he is an autocrat, but that he hasn’t been a cooperative one.) Washington’s not-so-tacit support for the (Saudi-backed) July 2013 coup against Egypt’s elected government removed any residual doubt that an America intent of preserving its hegemonic prerogatives can endorse moves toward real democracy in the Middle East.

Clinging to a Failing Policy

The only way out of the Syrian conflict is serious diplomacy to facilitate a political settlement based on power sharing between the Assad government and elements of the opposition. Russia, China, Iran, and even the Assad government have all acknowledged this. But, by staking out a maximalist demand for Assad’s removal, Obama and his European partners have severely truncated prospects for a negotiated solution.

This was on full display in the “Geneva II” peace conference in January. America and its partners insist that the June 2012 “Geneva I” blueprint for a settlement to the conflict requires Assad to relinquish power. This is, to say the least, disingenuous. At Geneva I, America, Britain, and France wanted language in the final communiqué barring Assad from any future political role; Russia and China insisted that such language be left out—and it was. Western powers have nonetheless continued claiming that the Geneva I blueprint bans Assad from being part of a transitional government or from standing for election after a settlement is reached—even though this is clearly not true. Washington and its British and French partners blocked Iran from taking part in Geneva II—even though Tehran is critical to any serious effort to resolve the conflict—precisely because Iran will not accept their warped reading of Geneva I as to Assad’s future. As a result, Geneva II has so far produced only limited relief for civilians in the besieged city of Homs, with no progress on the issues at the heart of the conflict.

As Syrian government forces continue making gains on the battlefield, Assad and his supporters may well be preparing a potentially decisive political challenge to the opposition and its Western supporters. Syria is supposed to hold its next presidential election this year—the first under the constitution adopted in 2012, which permits multi-candidate, multi-party elections. Assad and his government will work hard to hold this election—and challenge the opposition to run candidates against him. If Assad is able to hold the election, he will win—thereby underscoring his standing as the legitimate head of the internationally recognized government of Syria, and further marginalizing the opposition.

How many more Syrians will have to die before the United States and its partners get serious about conflict resolution in Syria?

Reprinted with authors‘ permission.

Flickr/Freedom House