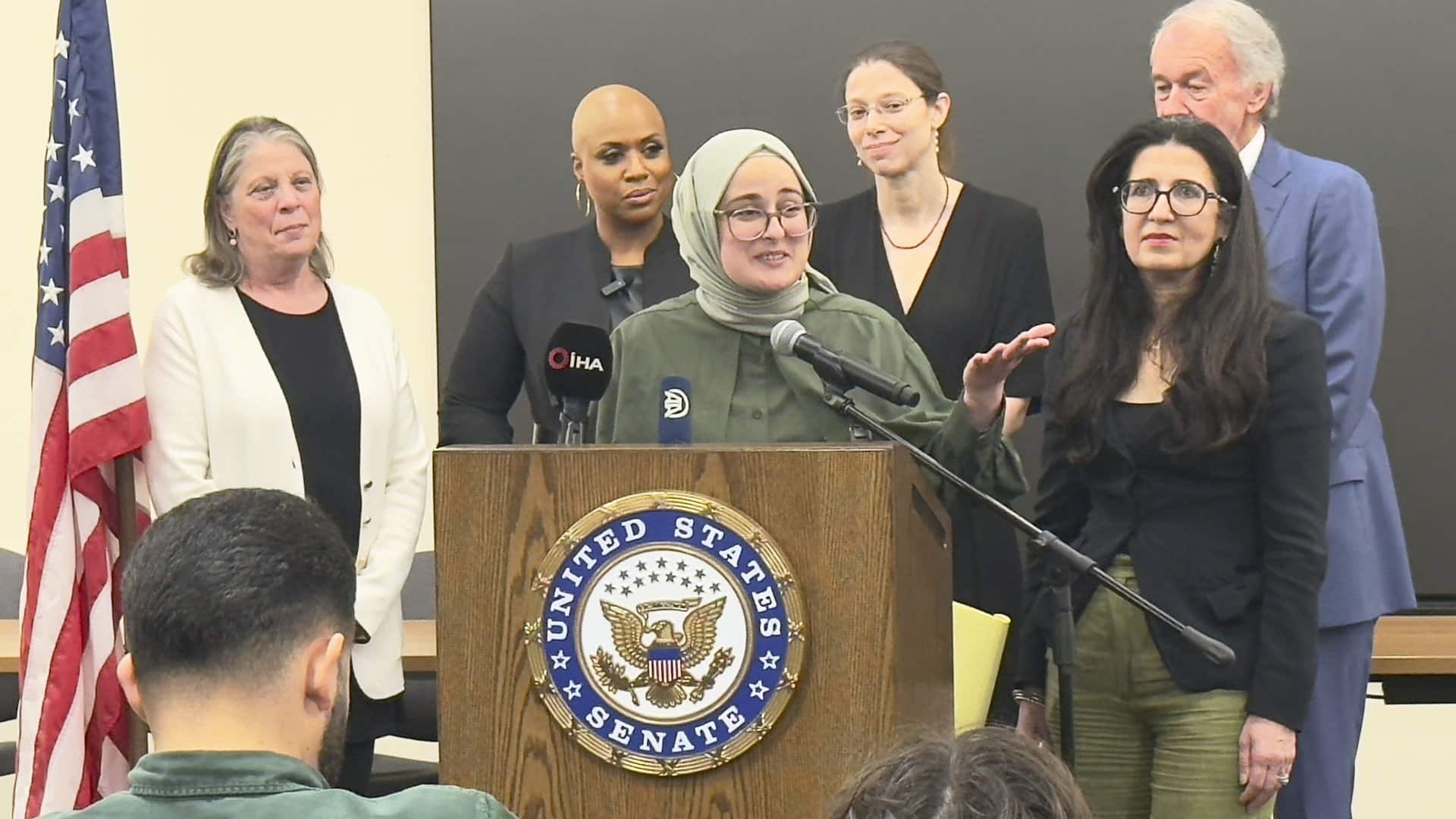

A federal judge recently ordered the release of Tufts graduate student Rümeysa Öztürk from custody with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In his ruling, U.S. District Judge William Sessions III said that Öztürk’s only apparent offense was co-authoring an op-ed critical of Israel.

This is good news for free speech and due process, but the Department of Homeland Security has said it will continue its efforts to deport Öztürk.

It is incumbent upon the administration to immediately disclose information about Öztürk’s arrest, starting with declassifying a State Department memo that concluded there was no evidence that Öztürk supported terrorism — despite the administration’s public claims that she did.

There is recent precedent for the government to declassify information that sheds light on its deportation policies, even if the release contradicts the Trump administration’s public rhetoric.

A declassified document recently obtained by Freedom of the Press Foundation (FPF) in response to a Freedom of Information Act request, and published by papers across the country, undermines the Trump administration’s rationale for invoking the 18th-century Alien Enemies Act to deport Venezuelans, allegedly members of the Tren de Aragua gang, to El Salvador.

Key to invoking the Alien Enemies Act was President Donald Trump’s March 15, 2025, assertion that Tren de Aragua operates in coordination with Venezuela’s Maduro government. The purported link between the gang and Maduro is important, because the act only allows the deportation of citizens of an enemy government — not suspected affiliates of an independent organization.

Shortly after Trump’s assertion, The Washington Post and The New York Times both reported on the existence of intelligence community assessments showing that most spy agencies overwhelmingly did not believe Tren de Aragua was coordinating with the Maduro government, seriously undermining the administration’s rationale for its deportations.

Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard said the leaks of information contradicting the government’s public assertions put “our nation’s security at risk.” Gabbard asked Attorney General Pam Bondi to open multiple investigations into the “deep state criminals” who had the audacity to inform the press that what the government was doing was wrong.

Bondi enthusiastically agreed and quickly issued a memo saying the leaks were illegal and made it harder for the Justice Department to keep America safe.

She also cited the Times’ and the Post’s reporting on Tren de Aragua as a reason to reverse a policy that protected journalists from having federal prosecutors seize their records or demand the names of their sources.

Yet, after maligning leakers for threatening national security and using the purported threat to undermine First Amendment protections, Gabbard’s agency almost immediately declassified the same information to me in response to a FOIA request.

This context is relevant in Öztürk’s case.

The Department of Homeland Security detained Öztürk on March 25. DHS had cancelled her student visa days earlier on the grounds that she supported a terrorist organization — ostensibly by co-authoring an opinion for The Tufts Daily calling on the university to recognize what the op-ed called “the Palestinian genocide” and divest from its ties to Israel.

But a State Department memo authored in March, the details of which were leaked to the Post, completely contradicts the DHS claim.

The memo, which has not yet been released, found that “Secretary of State Marco Rubio did not have sufficient grounds for revoking Ozturk’s visa under an authority empowering the top U.S. diplomat to safeguard the foreign policy interests of the United States.”

Somehow, even without evidence, a separate State Department memo dated March 21, “informed DHS that the revocation of Ozturk’s visa had been ‘approved’ under the discretionary authority.”

I filed FOIA requests with the State Department for both of these documents, arguing that the public has an urgent need to scrutinize the evidence behind the government’s deportations claims and to understand if journalists are being targeted for exercising their constitutionally protected right to free speech.

Not only has the State Department not released these records, they denied a request for expedited processing.

This is outrageous.

Öztürk and her lawyers deserve to have access to information that could aid in her legal case. And the public and the media have a right to know if the administration is arresting people off the street simply for writing things the Trump administration doesn’t like, as in the case of Columbia student Mahmoud Khalil, whose support for Palestinians was enough for Secretary of State Marco Rubio to label him a national security threat.

The State Department must release the memo showing there were not sufficient grounds for revoking Öztürk’s visa. The government is not allowed to hide information to prevent embarrassment or conceal wrongdoing, which is exactly what’s happening here.

And if the administration doesn’t want to disclose embarrassing information about its actions, it should stop making up reasons to deport people.

Reprinted with permission from Freedom of the Press Foundation.