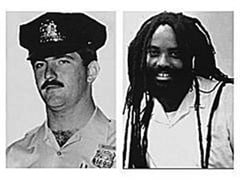

There has been some predicable and understandable objections to the selection of Mumia Abu-Jamal, the convicted killer of Philadelphia Police Officer Daniel Faulkner in 1981, as this year’s commencement speaker for Goddard College in Vermont. Faulkner’s widow and others have decried his recorded appearance from Mahanoy state prison in Frackville, Pennsylvania. However, as is all too often the case, politicians have responded to such good-faith objections with a highly questionable, poorly crafted law that allows victims to seek injunctions in future such cases.

Goddard College recognized Abu-Jamal as “an award winning journalist who chronicles the human condition.”

He addressed about 20 students receiving bachelor degrees from Goddard College in Plainfield, where he himself earned a degree from the college in 1996. He told them to

“Think about the myriad of problems that beset this land and strive to make it better.” While he did not discuss his crime, he such “Goddard reawakened in me my love of learning,. In my mind, I left death row.”

Abu-Jamal was a member of the Black Panther Party. He later became a radio journalist and president of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists. On December 9, 1981, Officer Faulkner was shot dead while conducting a traffic stop on a car driven by Abu-Jamal’s brother, William Cook. Faulkner shot Abu-Jamal in the encounter. The case became a national focus not only because of the death of a police officer but the later errors claimed in association with Abu-Jamal, who initially represented himself with disastrous results.

Abu-Jamal has become a symbol for some who view his cases as the product of racism and prosecutorial abuse. He has become a prison journalist and international figure. In the process, he has appeared before academic audiences in both writings and taped speeches. In 1999, he gave a keynote address for the graduating class at The Evergreen State College and, in 2000, he recorded a commencement address for Antioch College. He received an honorary degree “for his struggle to resist the death penalty” from the now defunct New College of California School of Law. In 1991, Abu-Jamal even published an essay in the Yale Law Journal, on the death penalty and his death row experience.

He has also appeared in national media. In May 1994, National Public Radio’s All Things Considered program enlisted Abu-Jamal to deliver a series of monthly three-minute commentaries on crime and punishment. NPR later backed down after protests and Abu-Jamal sued NPR for not airing his work. (The lawsuit was dismissed).

His publications include Death Blossoms: Reflections from a Prisoner of Conscience; All Things Censored; Live From Death Row, and We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party.

He was born Wesley Cook and was sentenced to death but his sentence was later reduced to life in prison without parole for killing Faulkner.

The new bill has been approved by a Pennsylvania House committee and would allow a victim to go to court for an injunction against “conduct which perpetuates the continuing effects of the crime on the victim.” It defines the conduct at issue as that which “causes a temporary or permanent state of mental anguish.” It would allow victims or prosecutors to ask for injunctions “or other appropriate relief.”

The bill in my view raises serious first amendment and other constitutional concerns. It is also dangerously vague and ambiguous. While I understand the outrage by many, the law would allow the curtailment of protected speech. History is replete with prisoners who have acquired educations during their incarceration and established themselves as writers or activists. Colleges and universities have also incorporated such voices into classes and events for decades. Universities are bastions of free speech where opposing (and at times even offensive) views are heard as part of an open forum. Just as Abu-Jamal was given a right to speak, his critics have been heard clearly in denouncing his selection. There are good reasons to question his selection, but the choice rests with the college and the students.

The bill is designed presumably to stop future such speeches, but to do so would curtail both academic freedom and free speech. The solution to bad speech is more speech, not censorship disguised as a victim’s rights bill. I have a huge amount of sympathy of Mrs. Faulkner and I understand the anger over the selection. However, this sweeping bill is not the solution. The solution is more not less speech. That is precisely what has happened. The national media has covered the controversy and many agree with the objections to the selection of Abu-Jamal.

While sponsor State Representative Todd Stephens insists that this legislation is about giving victim’s voice,” the victim already has a voice under the protections of the first amendment. The hundreds of articles hearing her voice is a testament to that system. Stephens appears most outraged not by any silencing of the victim but that fact that Abu-Jamal was heard: “I think it’s absolutely think it’s disgusting that this cop killer would be afforded an opportunity to address college students, frankly.” That is fine. Stephens has every right to be heard. What he does not have a right to do is to legislatively seek a way to silence the voices or prevent the choices of others in such presentations.

Current laws allow anyone to seek an injunction to prevent harm from the actions of others. However, such injunctions tend to fail when the harmful act is the exercise of free speech. Indeed, in 2011, the Court ruled 8-1 in Snyder v. Phelps, that tort laws cannot be used to enjoin or punish public speech, even speech widely viewed as “outrageous”. That speech involved the despicable protest by the Westboro Church of the funeral of U.S. Marine Lance Corporal Matthew A. Snyder (who was killed in Iraq).

Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall cogently explained inPolice Dept. of Chicago v. Mosley, 408 U.S. 92 (1972):

[A]bove all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content. [Citations.] To permit the continued building of our politics and culture, and to assure self-fulfillment for each individual, our people are guaranteed the right to express any thought, free from government censorship. The essence of this forbidden censorship is content control. Any restriction on expressive activity because of its content would completely undercut the ‘profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.

Reprinted with permission from author’s blog.